Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How the creation and growth of an economy as a tool for achieving your goals forms the backbone of multiplayer gameplay in Eco.

VentureBeat put up a really great series on Eco last week about, about their experience in the virtual economy. Jeff Grub writes:

"I attempted to destroy the friendly bartering/communist ecosystem that was keeping me and a dozen other players fed and advancing through the sim’s various skilltrees. I was of the opinion that we needed capitalism. The profit motive, you see, would encourage people to work toward larger goals instead of their personal projects. Maybe that will still happen, but for now, my capitalist dream has led to bickering, greed, and a financial crisis. And I’ve decided to destroy my currency’s value in response."

It’s really encouraging to see the mechanics we built playing out with the richness and depth that gets described in this article and others, as the incentives of the economy twist a group with the same ultimate goal (destroy the meteor) into a dangerous financial conflict with potentially world threatening consequences. It’s a microcosm of the interactions (good and bad) between government, economies, and the environment we see playing out in the real world, caught inside a microcosm game world.

I see this kind of exploration of economies as having a huge potential for games (both in entertainment value and beyond) and this article details some of the things we’ve built and are building in Eco in that direction.

People generally associate the name of our game Eco with Ecology, but it was chosen because it’s also the root to an equally important pillar of the game, the Economy. The name ‘Eco’ belies the underlying connection of the two that forms the foundation of the game, and you, dear player, must navigate their tangled combination as the core of the gameplay.

One of the most important differences between these systems is that the ecosystem we created runs as a simulation, influenced by players but maintaining a life of its own; it will continue doing its thing even if no one is online. The economy, by contrast, is basically entirely player controlled. It’s a tool they create from the ground up to organize human activity in the world, using the incentives and penalties it generates to best guide a disparate group of players, each with different specialties and interests in the game. It’s a tool to better achieve your goals in the game, both individually and as a group. Essentially, you’re wielding the Invisible Hand of economics to make better decisions as a society, in a setting where no one holds full knowledge or skill.

Items wanted for purchase on the Eco Server ‘MagLand’

This is of course the economy, but it’s pretty rare in games to experience them in games as their creator. It’s very common, to have systems in games where you’re a participant in an economy, acquiring goods or currency and trading them for stuff that you want like weapons. Usually these economies are static with prices remaining fixed, but there are games where those can change as well, leading to interesting dynamics of trade as supply and demand fluctuates, which becomes a game within itself. A ton of richness can come from this simple flexibility.

That’s really the tip of the iceberg in terms of what you can do with gameplay through economies though, and in fact a lot of traditional mechanics of games (not at all related to currency) can be framed in terms of economic theory. Health cost, weapon damage, incentivized behavior. There is a reason game theory (emphasis on ‘game’) is such an important foundation of Economics, and its because the two are deeply intertwined. One of our goals with Eco is to explore that further, tying it to other rich systems that raise the stakes of the outcomes, specifically, the ecosystem and player government and societal progression. We want the economy of the game to be a weapon you wield in pursuit of your quest, one which is very much a double-edged sword, and there are many ways it can be applied.

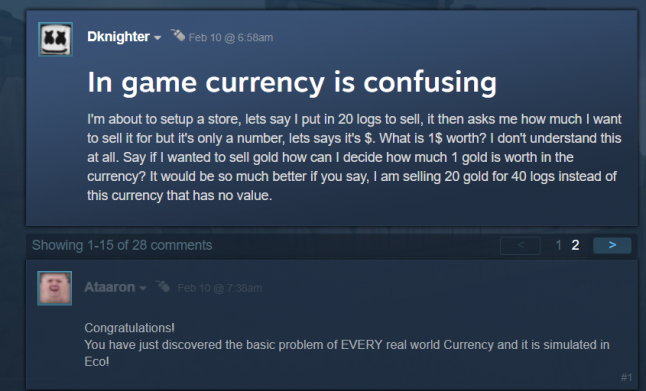

One of the foundational requirements in an economy that’s built from the ground up is to establish a currency of exchange, a concept that gets you closer to the heart of understanding what money really is. Looking closer at the idea of money reveals a lot more complexities than is visible when you’re just collecting gold coins and spending them, and previous concepts of it begin to transform. One of my favorite threads on our Steam Forums is this one, in which a player struggles with this concept (and I hope learns something valuable in the process):

The answer to ‘what is one gold worth’ is of course ‘whatever people think it’s worth’. Understanding that is step number one to seeing through the illusions of currency and markets, and it turns out it’s a really fun one to play with.

In Eco everyone has a personal currency (‘JohnK Credits’ for example) for which they have an infinite amount. I can give and take as much credit as I want after all, since its just all in my ledger that it has any meaning. This allows players to go beyond basic bartering (I’ll give you an axe for 20 pieces of corn) to a more fluid medium of exchange, which can be split infinitesimally, stored for later, and even exchanged in transactions that don’t involve me (Bob can sell Jane their JohnK Credits for 10 logs, for example). So you start the game with this currency that you’re able to trade with right away.

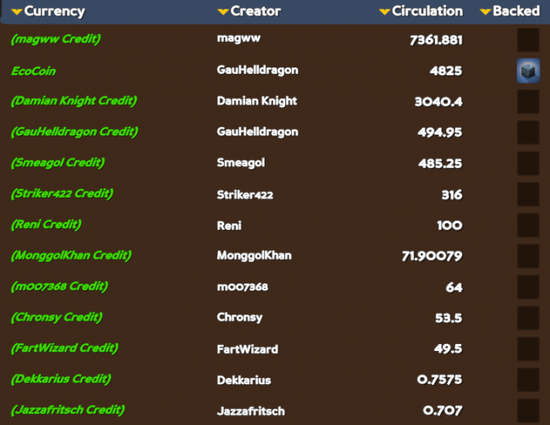

Currencies in circulation on MagLand. The EcoCoin is their official currency and is backed by stone.

The fundamental problem with this (which is intentional in Eco) is that since the currency is unlimited, I can simply create as much as I want at anytime to buy anything that’s for sale in the market in that currency. There’s no stability, and entrusting your livelihood in JohnK Credits is incredibly risky because its value could collapse at anytime. This is what happens when there’s no scarcity of the resource: I have infinite credits, thus infinite buying power, and the system is inherently unstable.

So, to solve this, players need to introduce scarcity. With scarcity there is stability; you can have some assurances that the currency wont devalue to a millionth of its former value overnight, because it’s based on something limited. In Eco you can build a mint and turn certain resources into coins: gold, stone, wood, whatever. Generally, the harder it is to get the backing item and the more of it you have in circulation the more stable it’s going to be. As the economy grows in Eco, it’ll reach a critical phase where there are so many currencies in use that it becomes difficult to effectively trade, and it will be very advantageous to unify them into a single currency. This is not an easy process, as Jeff from Venture Beat found in his world, and one fraught with tempting opportunities for exploitation:

"My first suggestion was a transitional period where my store and the other accepted the old currency without buying anything new. This would give people with savings time to spend their credits. I would then want us to create a stimulus package where everyone gets the same amount of the new universal currency so that everyone is bought into it and has something to spend. This would kickstart our economy because everyone has different purchasing needs, so everyone could set up a store that could succeed. If one person starts with more of the wealth, people are better off trying to compete for that person’s patronage.

But the people — and especially the person who created the mint and in effect controls the new universal currency — would rather we just do an exchange. He had the most Grubbucks, and he wanted to keep his wealth. People argued that people shouldn’t lose what they have accumulated just because we’re moving to a new currency — and I get that, but it ignores an important point: the haypenny isn’t just replacing Grubbucks and Zackbucks, it’s also going to replace a significant portion of the barter economy that has served as the primary transactional system up to this point.

I think it’s an awful idea to only reward people who acquired the worthless Grubbuck and to put the people who did repetitive labor tasks in the mine and bartered at a disadvantage.

But I’ve found a solution to my problem: inflation."

Monetary policy, perhaps thought of as one of the most boring things in existence, can become an interesting mechanic within the right framework. That reaches to the core of the video game medium’s power, and why I believe the reason why games will transform education. Once a subject like monetary policy is connected to other things you understand and care about (your progress in the game), it instantly becomes interesting and useful. This is what is most lacking in education and what games provide so well: a reason why you should care about what you’re learning (future article on this coming).

Many games have a quest system, where you perform some task in exchange for money. Usually they’re created by the designer, but when you put quest creation in the hands of the player they become something much deeper. No longer are players completing quests for arbitrary hard-coded reasons, they are creating value needed by other players, connecting to the network of systems in the game, even back to the original quest-taker.

A list of contracts available on the MagLand server.

In Eco, because you need to specialize in skills, there are plenty of things you’re not able to do on your own but will greatly benefit you, and for these we built the contract system.

A list of available contracts posted by various players.

Contracts are created by players as a collection of clauses, which determine requirements and results. The ‘Build Road’ clause dictates two points between which a road must be built to satisfy the contract. The ‘Transport’ clause sets a manifest of items that must be moved from point A to point B. The ‘Payment’ clause determines the deposit taken when accepting the contract and the amount repaid on completion. The ‘Build Room’ clause sets the location and type of construction you want done. The ‘Reputation’ clause limits acceptance to only players with a defined reputation. By composing and configuring these clauses, players can craft a precise description of the work they need done, who they would like to perform it, and the compensation they will offer. This work can then be accepted, performed, and compensated asynchronously, allowing work to happen between players without the players knowing each other or even being online at the same.

A contract for stone collection.

Gameplay wise, this satisfies multiple goals: players can get things done that they can’t do themselves, they can be incentivized as to where to target their skills (by looking at the job market and what is needed), and they are able to help each other without needing to fully understand the results of their labor in the grander scheme. They can thus collaborate without trust, allowing interesting interactions between strangers.

This last point is especially interesting, and has impacts on the culture surrounding games. When everyone you meet in a game is an enemy who must be destroyed, that mentality can seep into the outside community. This can range from the friendly competition of a soccer game to the modern shooter bloodbaths, with cultures that match accordingly. I believe that the often sad-state of gamer culture comes from these kinds of interactions being the primary way you connect to your fellow humans in a virtual world. What’s lacking is a way to meaningfully cooperate with strangers, even with unshared goals, and when you have that trust can exist between strangers and build overtime it turns it into a much different kind of connection.

Non zero-sum markets like this, in which both participants end up better-off than before and value is generated, have been the lynchpin of civilization from our earliest days. Perhaps the lack of these systems in games is related to the negative culture of games that’s alubiquitous. Don’t get me wrong, there’s certainly a place for the role of zero-sum conflict among strangers blasting each other to bits (or just taking each other’s Chess pieces), but the fact that there’s an unexplored alternative is a big opportunity in game design and what I think is likely to move the medium forward.

A player store in Eco.

With currency and contracts together comes the possibility for a new feature (which I’ve just finished adding, coming to a not-too-distant build) of player financing. Eco will soon have the ability to offer loans and bonds to other players, backed by collateral defined by the lender. Players will now have the ability to get a leg-up in the game, drawing against future-earnings in order to create an enterprise that will generate those future earnings, and the lender can be assured of their risk reduction through collateral, which can be defined as the player’s property and house, for example.

It also opens the door for the financier profession: players who issue bonds to acquire wealth then lend it out at a profit, playing banker within the player-defined economy. You can get rich this way without performing manual labor, instead functioning as a knowledge worker: making astute decisions about whom to lend to and borrow from. There is actually a huge amount of value in this role, these players are functioning as organizers of goods and labor across the world, and their success depends on their understanding of it.

There’s also a huge potential for failure, and I fully expect problems we see in real-world finance to quickly emerge in Eco. There’s a natural incentive to downplay risk in the face of profits, and ‘irrational exuberance’ could generate huge problems for a world’s economy. Simple greed can take hold, with players hoarding funds, or over-harvesting or polluting ecosystems in order to maximize profits, perhaps swaying elections with lobbying funds to change the laws in their favor. I very much hope to see a mortgage finance crisis bring down more than a few worlds in Eco.

The complexity you get out of these financing systems can become a big focus of the gameplay, with actions that can be genuinely debated to be positive or negative for the world, with the participants heavily incentivized to believe one interpretation over the other. If I’m financing a set of loggers, I might want to put some of my profits towards preventing that anti-deforestation law from passing, or else I’m not going to get all this debt paid back to me.

That’s the kind of conflict that I think is interesting, not the brutal, basic conflict of combat, but the grey-area, nebulous, complex conflict that arises from shared resources and economies. The astounding part is you don’t need to be enemies to be brought to this conflict, you can have exactly the same long-term goal (prevent the meteor impact), and through differing incentives and biases you can arise and world-destroying consequences. Games have sat so long in the simplistic confrontations of good vs evil, X vs Y; meanwhile, an unexplored continent of complex shared problems waits to be explored. This is our step in that direction.

Having this economy/ecosystem simulation is such a fantastic toybox for a designer, and I’m excited to keep pushing these systems into new territories, connecting more player-run systems to each other and seeing what emergent situations pop out.

A big step will be company incorporation, allowing players to form new companies that have certain legal protections and possibilities. The corporation is responsible for so many of the goods and ills of our modern day, and how those come about from a structure that is tied to no single individual is fascinating. With an incorporation system, players can create new entities that issue contracts, hire people, pay taxes, harvest resources from the environment, and lobby the government. I want to see these corporations grow outside of the control of any one person’s will in the game, taking on seemingly uncontrolled directions in the pursuit of profits, leading to either success or destruction of the world. They would essentially allows players to amplify their energies by combining into a shared entity, and the mechanics of creating and managing and performing that will have endless interesting permutations. Stocks, derivatives, bankruptcy, ‘the corporate veil’ and more will all have places within that.

Another big step is connecting this economic engine in deeper ways to government. It’s often take as the role of government to ensure that the economy serves the people, regulating it to promote the common good (or not regulating it, depending on your school of thought). Giving more levers on the economy for the player government to control will be a big addition, with things like fiat currency, controllable interest rates, stimulus packages, licensure, government property control, and tax incentives and penalties all having a place. Conversely, I would love to see interactions in the other direction, with corporations working to sway the government: lobbying, graft, election campaign funds, and all the kinds of messed-up stuff you see in our day to day world will definitely find their way into Eco. Humans are humans, virtual or otherwise, and if we can build a mirror with this game to experience the same patterns of creation and destruction that impact our real-world, that will give us a view into their origins and how to better ourselves in order to prevent them. And they’ll just be a lot of fun, too.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like