Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

What can Hardcore Mode in Resident Evil 2 offer beyond tougher enemies and scarcer bullets? A look at how content-based difficulty rewards survival horror fans.

Resident Evil 2 is a masterwork of remakes done right. Gone are the artistic yet constricting fixed camera angles and in with dynamic survival horror experiences. The modern over-the-shoulder view jams players into suffocating corridors and the precarious combat system triggers a masochistically addicting fight-or-flight reflex at every frightening encounter. Capcom implemented effective design choices throughout the game, yet other elements that would naturally compliment those choices were no where to be seen.

In 2019, games have access to unprecedented technology that allows for more complex systems for players to interact with and more innovative mechanics to evolve familiar experiences. Resident Evil 2 offers several difficulty modes that mirror traditional games with the escalation of mechanics like tougher enemies and fewer resources. Fellow Gamasutra contributor Alex Vu writes extensively on how problematic this decision is for players to make upfront before knowing anything about the game they are starting and the difficulty in crafting solutions that both resolve these issues and preserve immersion.

While the existing Hardcore Mode in Resident Evil 2 is valid, the offering is flat and begs whether the genre in our modern age of gaming can amplify the survival horror experience with unique features that it is poised to do best.

Here are 5 things that can elevate Resident Evil 2's Hardcore Mode to the next level.

(Resident Evil 2 features Leon Kennedy and Claire Redfield as playable characters. For fluidity, Leon will be the reference point for the player's character in this article.)

When Leon is attacked by a zombie, he can escape with a handy knife to the chest or grenade to the face if he has the subweapon equipped at the ready. This is a thrilling split-second decision that pits resource management against survival - a fitting addition to the game in terms of mechanics and immersion. Should the player be caught without a subweapon, however, there is zero interactivity and the zombie simply chops a chunk of your health away after the usual struggle animation.

From my playthrough I found it strange that I am more engaged in this moment when I am more readily armed than when I have nothing but my will to survive. Why am I not driven by the game to struggle even harder in this more dire scenario?

Perhaps it is more defeating if the player has no recourse to this punishment, but I argue that a survival horror game like Resident Evil excels at maximizing an engaging and thrilling experience for players when it counts. Instead of breaking immersion by removing agency from the moment, the game could allow an interaction where the player can break a zombie's grasp by mashing all the buttons as quickly as possible within a window set at a variable time. This interaction is present in previous titles, notably the trend-setting Resident Evil 4, and its absence alongside the new subweapon counter option is puzzling as it is perfectly complimentary to the new system both mechanically and experientially.

When a player is prepared with a subweapon, countering a zombie attack is as graceful as tapping the L1 button once with ease and confidence in the outcome. This action the player performs parallels what Leon is experiencing in-game so immersion is preserved and enhanced.

When a player is caught empty-handed, a desperate wrestling match erupts where the player must mash the controller furiously hanging on to a sliver of hope for survival - all the while, flashes of regret and lack of preparation storm through the player's mind, promising himself that he'll do better next time if there is a next time. Just like the existing interaction, this mash-out option also parallels what Leon is experiencing on screen. The player's furious mashing mimics Leon's palpitating blood flow and this experience enhances the thrill and immersion that continues clamping the player to the game.

Such a minor gameplay tune amplifies the captivating experience Resident Evil 2 already offers and naturally fits into the baseline gameplay. Doubtless its absence was an intentional gameplay decision, but I find that its inclusion advances the survival horror experience so well as to warrant a serious consideration. More gameplay tunes like this may be neatly integrated into the default experience or, if found too difficult, can be relegated as a feature of Hardcore Mode.

Resident Evil 2 mixes up the replay value by shuffling enemy and resource placements in each character's B route. While a nice touch, it echoes the same experience from A route where the scare is over after the first pass. A stray zombie can nab you in that one corridor during one of your numerous playthroughs, but the player will basically know exactly what to expect each run.

Thomas Grip, another Gamasutra contributor, wrote, "The worst thing about combat [in horror games] is that it makes the player focus on all the wrong things, and makes them miss many of the subtle cues that are so important to an effective atmosphere. It also establishes a core game system that makes the player so much more comfortable in the game's world. And comfort is not something we want when our goal is to induce intense feelings of terror."

Resident Evil 2 highlights an improved combat system that allows the player to manipulate zombies with a greater level of control by firing at different body parts. Other features like the ability to retrieve a knife used for a defensive measure and standing still to increase your accuracy are all useful, but they miss the mark in creating an effective atmosphere by focusing on what you can do to your enemies but not what they can do to you.

The creatures of the night are infinitely more terrifying when the player cannot anticipate what they will do to you. Instead of punishing the myriad of ways the player can fail to bypass enemies with the same outcome (damage), variance - another fear of the unknown - is created when enemies can interact with the player in more diverse and unpredictable ways.

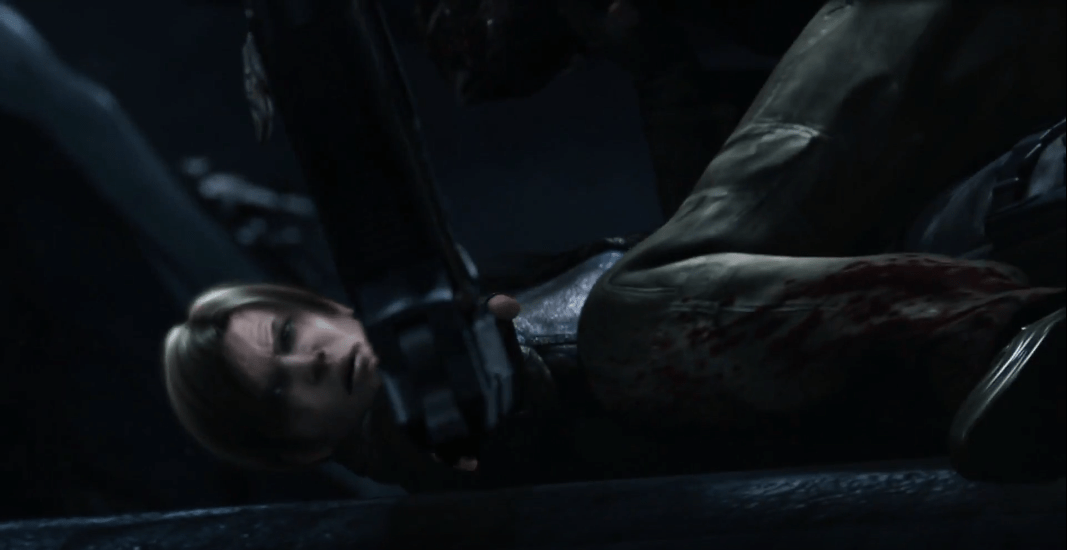

For example, when a zombie latches onto Leon up close, the standard struggle ensues. But if a zombie latches onto Leon after running a certain distance, then there is a 50% chance that it will knock Leon onto the ground and send his weapon flying across the room. A unique animation triggers where Leon must break free from the zombie and then scuttle over to retrieve his firearm to continue the fight. Just as the player can land critical head shots, zombies now can perform critical hits of their own on the player that amplify the game's mechanical demand and cinematic experience. When your gun catapults through the air and the camera pans onto Leon's distraught face, the game is on. This is a scene straight out of a horror film and what happens next all rests on the player's shoulders.

Applying this design to the first point, imagine a zombie rams into Leon and both are slammed against the wall. Like the melee system in The Last of Us, enemy interactions and animations can adapt to where Leon is in the environment. If he gets grabbed in the middle of a hallway, a normal struggle triggers. But if Leon is slammed against a wall, then there is a chance that mashing the buttons long enough will cause the zombie to drag Leon onto the ground where the struggle continues even longer. The seesaw between survival and futility clasps the player fiercely into the encounter as he breathlessly mashes the controller for his life.

Mechanics like this demand more perceptive animation reading and reward the player with a new experience that would otherwise be unseen by the less gutsy. For a survival horror game, a Hardcore Mode deserves a contextualized approach on its own terms that is more sophisticated than simply splaying tougher enemies or fewer resources before the player.

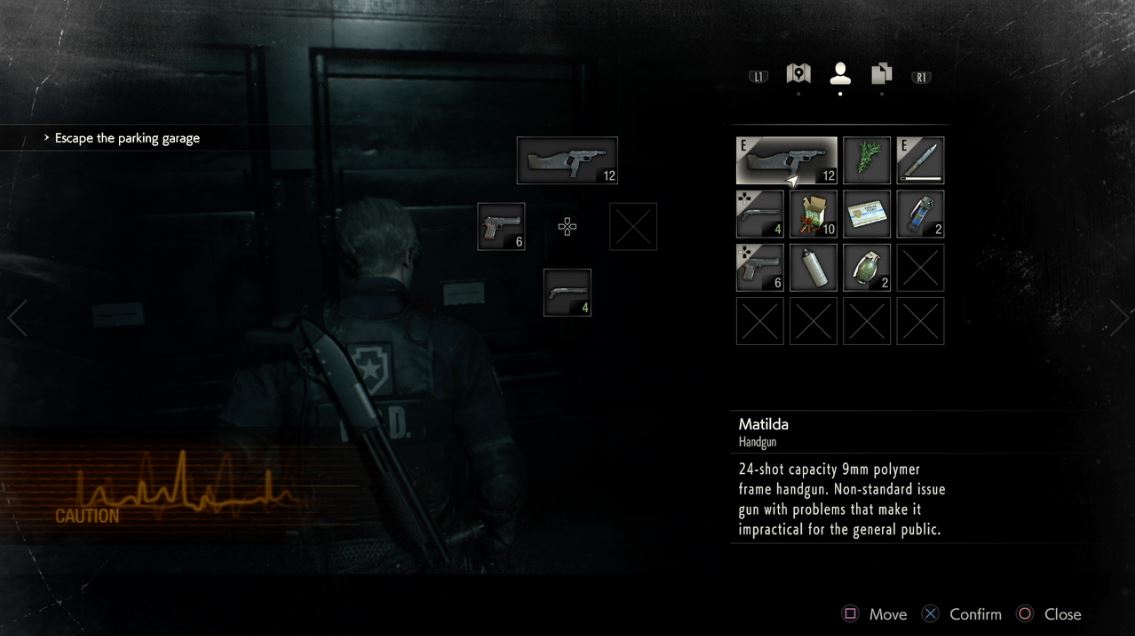

This system tune is another natural fit as it already appears in Resident Evil Outbreak, Resident Evil 5, 6, and 7. A real-time inventory menu makes resource management and exploration even tenser by disabling mechanics like unpunishable healing on the fly.

Nothing says "game-y" like pausing the game and popping your potion. While Resident Evil 2 isn't necessarily a zombie apocalypse simulator, its previous titles have proven that a real-time inventory can work in the series and its inclusion in at least the Hardcore Mode would add a new dimension of difficulty. Though not as severe as Breath of the Wild where the player has literally three ways to stop time (one even allowing the player to teleport anywhere on the map), Resident Evil 2 appears to drop a key lesson learned in this regard in favor of preserving a traditional tone from its first incarnation.

Like popping flasks in Dark Souls, healing would require a real-time animation that may be interrupted by enemy attacks. This throws another wrench into the already unreliable combat that exacerbates the vulnerability of the player and encourages retreating instead of re-engagement after tanking some hits. Leon looks just a little bit too level-headed up against the undead horde so a mechanic that facilitates our flight instinct reinforces an appropriate experience in the game.

This is a small tweak but it vastly changes the system of the game that morphs how the player approaches the entirety of their nightmare. This is distinct from a change in the environment where enemies deal more damage or resource locations are shuffled around. The current Hardcore Mode implements a key system change with the Ink Ribbon save system so it is reasonable that the development team are aware of the tools available to them and we can hope that a remake of Resident Evil 3 may offer a further evolution of the new formula.

Resident Evil 2 is a survival horror game. The only way out is through. There is no escaping the nightmare. The tragically canceled P.T. is a prime example that crafts an utterly oppressive atmosphere that makes a player regret turning the game on. Each moment the same thought chips away at the player's psyche: "Is it over yet?" Survival horror soaks each step forward with heavy dread, tearing the player in two between staying safe where they are or advancing towards a hopeful unknown. All the while, this constant teetering is rattled by the ever-present fear of death.

When Leon dies in Resident Evil 2, an iconic feasting animation runs its bloody course as the player is forced to gape at his grizzly death (although perhaps less gruesome than Lara Croft's fates in the Tomb Raider reboots). After a few torturous seconds, the player is treated to a relatively clean "YOU ARE DEAD" screen with the option to continue or quit.

This is a survival horror game. You have no choice. Get back in there.

To take a page from one of survival horror's most successful titles, The Last of Us executed just this in 2013. When Joel or Ellie die, the screen ignites with blood-curdling shrieks followed by a sharp cut to black that ripples through the player's soul. A few moments of respite, and the player is immediately thrusted back into the fray from the last checkpoint.

Such a clean mechanic preserves flow (by picking the option the player would likely pick anyway) and reinforces the genre further by emphasizing the oppressive atmosphere. You, the player, are trapped in this nightmare. The only way to satisfyingly escape is to do what you know you need to do. Feel free to exit this "game" on your own accord, but we both know what this is about. Find a way through.

Just as books are conversations between the reader and the author, video games as an interactive medium are no less this back and forth communion between player and designer. The game is a clear conveyance of the designer's intent, and for a survival horror game, its ability to resonate with the player rests on every design decision. Each death screen in Resident Evil 2 asks the player, "Are you okay? It's okay if you're not. If you're not feeling it, we can make it easier for you if you'd like."

Players buy into a survival horror game to feel like they are trapped in the game world fighting hard to survive. The punishment of death reinforces the nightmare loop by forcing players to go forward, not by offering a way out. A small but pivotal design choice like the death screen powerfully preserves and amplifies the oppressive experience of the genre, and Resident Evil 2 is strategically situated for such design.

Content-based difficulty is the overarching paradigm discussed throughout this article that can elevate the survival horror genre to new levels of hardcore.

Traditional hard modes in video games are essentially number bloaters. More enemies, more health, more damage, more attacks, and more death. And this is valid! Genres like hack 'n' slash or action RPGs appropriately benefit from number bloating, but the survival horror genre is special because it is an experience that is out to scare you.

As game designer Jesse Schell elegantly notes, players are paying for a trip to a Disneyland designed just for them. In this case, a corpse-filled nightmare fuel Disneyland. Enemies that deal more damage to you are like a rollercoaster that has two speeds. Once you ride it at normal speed, you get it. Riding it again on hyper speed may be more fun but you'll just be frustrated when you eventually vomit.

What players really want from the ride is to take that left fork that they passed by the first time and see where that dark tunnel leads.

Surprise. Change. The unknown. These are the stuff of scares, not a higher speed.

How can content-based difficulty look in Resident Evil 2? Just ask this gentleman.

In Bloodborne, the Snatcher is an enemy that spawns in a familiar location after a certain event triggers in the story. If the player is felled by the Snatcher, there is no rote death. The player is treated to a special animation where the Snatcher kidnaps the player and dumps them into a prison cell in an unknown location with no way to return to where they came from. The change is stark, relentless, and the player must advance into the unknown - fully equipped yet fully rattled.

Now what other tall, cloaked gentleman could adopt a similar behavior?

In Resident Evil 2, Mr. X punches you and that's about it. Sometimes he can kill you with one hit. Like the rollercoaster, Mr. X loses his bite after your first tussle with him (and especially after you figure out how to exploit his pathing). For such a formidable design, Mr. X is largely relegated to a simple DPS role on the enemy team. Whether he's stalking Leon or fighting him directly in a boss fight, he only does one thing - deal damage. The immersion crinkles eventually and Mr. X becomes an environmental hazard to avoid instead of a sentient force you need to respect.

At a certain point in the game, what if Mr. X defeats Leon then plunges his unconscious body deep in the depths of the Umbrella nest? The door is locked. Four switches with different colors flash on the keypad and there is a ventilation shaft that looks suspiciously brittle. A fate more hardcore than death.

Content-based difficulty is a new paradigm that fundamentally changes the way survival horror games are designed. It is no simple number tweak yet maximizes precisely what the genre can offer best for its fans - the truly scary stuff to those brave enough to behold it.

The implementations are limited only by the imagination, and while the correct solution to the difficulty challenge in survival horror games may not materialize just yet, we can rest in the words of Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami: “To be honest, it’s hard to make survival-horror work as a game. Should you emphasize the entertainment aspect and focus on the fun of killing enemies? Or should you try to aim for more of a creeping sort of terror? It’s hard to strike a balance . . . "

With content-based difficulty and more tools to come, we continue innovating to build on Mikami's legacy and to unleash upon the world all new nightmares evolved.

References

A Different Approach to Difficulty (2018) by Alex Vu. Retrieved at http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/AlexVu/20181023/329199/A_Different_Approach_to_Difficulty.php

10 Ways Horror Games Need to Evolve (2012) by Thomas Grip. Retrieves at http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/169476/10_ways_horror_games_need_to_evolve.php#.UOXnDORWySp

Jesse Schell Talk @DICE (2010). Retrieved at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLwskDkDPUE

The Biggest Name in Video Game Horror Never Made Horror Games at All (2017) by Anthony John Agnello. Retrieved at https://www.avclub.com/the-biggest-name-in-video-game-horror-never-made-horror-1819921166

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like