Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This harrowing game, set it a real mental hospital that was closed in the 1970s, turns your stomach not with blood or gore but with a deep understanding of its protagonist's personal hell.

Playing The Town of Light while drinking wine was a mistake.

It's not that the game, released earlier this year by LKA, is especially gory. The knife it slips into you is a slow, subtle thing, and by the time you realize it's turning you're far too deep into the experience to do anything about it. The game turns your stomach not with blood or gore but with a deep understanding of its protagonist's personal hell.

Renée is a young woman sent to a mental hospital at age 16 in Second World War-era Italy. You play as a present day character--Renée herself? A ghost? Someone who hears Renée as a voice in her head?--exploring the hospital's ruined grounds.

Interestingly enough, the hospital is real. The Ospedale Psichiatrico di Volterra, nestled high in the scenic hills of the eponymous town, was an infamous place until its closure in 1978. Town's developers at LKA did extensive research on the facility, a sprawling campus that housed both civil and judicial sanitariums. Renée emerged from their studies as a composite character who, like many that passed through the Ospedale's halls and never left, suffered far beyond the limits of endurance.

The actual abandoned asylum. via Eleonora Castagnozzi

The actual abandoned asylum. via Eleonora Castagnozzi

This is portrayed with compassion and care; it's all too easy to make a game about madness that makes a spectacle of mental illness and promotes lurid gawking rather than understanding. That I wanted to look away so often was, perhaps, a marker of success; the pain was visceral and real even when sketched in the beautiful 2D comic book style of the game's cutscenes. Further, the game underscores the iatrogenic element of Renée's madness; the dehumanizing conditions of the Ospedale were such that they would rob any person of their senses.

As Atlas Obscura noted:

“Practices such as electroshock treatment and the inducement of comas with insulin were common, and there was a manual of pills and poisons administered for testing purposes to the patients, with complete disregard for their often-irreversible consequences. Inmates were often sedated, isolated, or placed in tanks full of ice. The rooms had prison-like grates and nurses were addressed as ‘guards' or ‘superiors.'”

This was not a place for human life, as Renée's story makes clear.

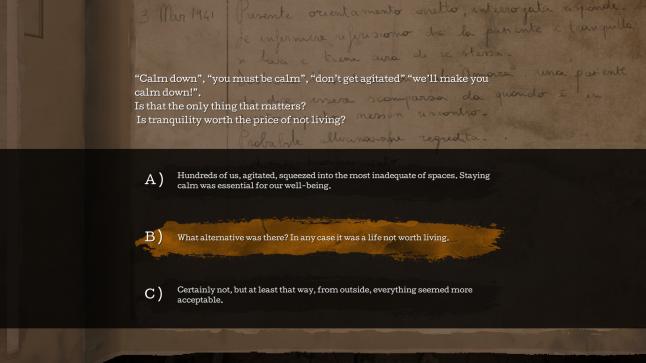

The gameplay conveys this through a combination of the dreamlike psychodrama of Dear Esther and the tactile exploration of Gone Home, though it is more involving than each as there are minor but notable puzzles to be solved; there are also strange dialogue choices (are you talking to yourself? To a ghost?) that alter the course of the story.

"Through the course of the game's narrative, you dive headlong into memory, time lost as you warp between the early 1940s and the present."

As with Dear Esther, though, who you are in the game is unclear. You occasionally see your hands, those of a woman with chipped nail polish, but that's all. Through the course of the game's narrative you dive headlong into memory, time lost as you warp between the early 1940s and the present. The sun cycles across the sky and you wonder how long you've been here. Two days? Three? You speak in Renée's voice and yet she argues with herself, sometimes sounding like she's sixteen again, others like she's in her thirties or forties. It all combines for an unsettling and beautiful tableau.

As always, one must ask before making such a title: “why does this need to be a game?” The experience has to answer that question, and Town of Light's is exemplary. Playing through the narrative feels like being both an unstable haunting and a 21st century urban explorer.

But at every stage, Renée is with you and you experience what her terrors looked like in elaborated, three dimensional impressionist hellscapes of modern medicine. A ward becomes a neverending series of Escher-esque corridors that twist on themselves, childhood is a garish maze of a house with hideous wallpaper and too-clean chandeliers. The cutscenes have much to recommend them as well, but it's the moments where you're in a semblance of control that are the most unsettling.

The way the game takes control from you could be handled more artfully, of course. It ceases to be terribly involving when your only ludic contribution to advancing a nightmare scene is holding down the ‘W' button. But I can't be too harsh when so many of those scenes stayed with me, and even the push of a single button implicated me in such moving moments.

"The “truth” is something you construct based on your interpretation of the game's events, and this is perhaps the most interesting part of the game mechanically."

The “truth” is something you construct based on your interpretation of the game's events, and this is perhaps the most interesting part of the game mechanically. In your dialogue (inner monologue?) with Renée you're given different ways to affirm, challenge, or outright deny her take on events, or answer her own doubting questions--particularly when she compares her slowly-returning memories to the cold medical reports she finds strewn throughout the ruins. In so doing, you open up different scenes entirely, or make certain characters appear.

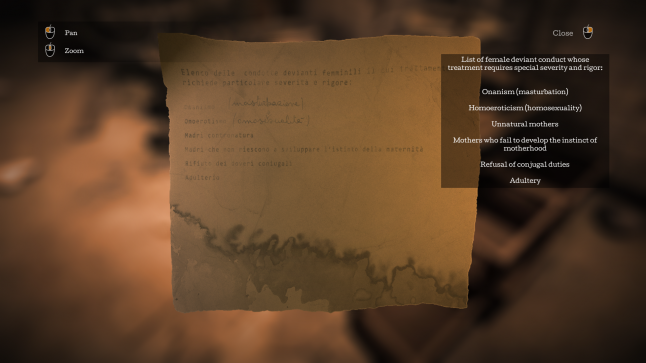

Consistently, however, Renée's story is one where her womanhood was pathologized. It's difficult to elaborate on this without spoiling the game's revelations, each of which knocks the wind from you, but it is enough to say that this game explores the terrible gendered meaning of “hysteria.” There are many shades of Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" here--certainly a triumph for a videogame to recapitulate--but it is far less genteel.

Renée was not real, but her experiences were drawn from those of countless, nameless women who wandered those halls like ghosts and zombies--an effect captured with painful precision by the game's narrative design. Those moments where you wake, tied to a bed, surrounded by gaunt faces lined with pain are the ones I'll truly remember. The details of the environment haunt you, even during daylight hours with pastoral Tuscany visible through windows and surrounded by birdsong, you notice a bed with an hole in its mattress. One intentionally made so that patients who were tied to a bed could defecate into a waiting bucket below.

Town of Light uses something far more potent than a jump-scare to frighten you: the truth.

There was a moment in the game where I thought the way back to the Ospidale was barred and so I fled to the point where it all began, the road back to Volterra, thinking “this must be it, the game is freeing me, this must be the end.” It wasn't. The way was shut; I had to go back. In that split second, I think I just touched what must've been Renée's emotions.

For all the right reasons, the longer you play the more you want to claw your way out of confinement. It's all so rational--the game all but tells you where to go--and all so senseless. Debris magically clears itself. Doors open and lock shut by themselves. You have to push a wheelchair around the hospital that carries your favorite doll. In tone, form, and content, the developers at LKA nailed it. They seemed to grasp the fact that the truest horror stories are the ones we've created for ourselves throughout our history. The Ospidale needs no supernatural spice, its strangeness comes from the madness we inflict on our fellows.

As the credits roll through a dreamy pop soundtrack, the music eventually fades out while the animation pans over the sun-drenched Tuscan hills; no sound but birdsong fills the air. With the delicacy of a string quartet, the game brings us back to the clean surface of ordinary life where we can pretend Renée's terror is just a game.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

You May Also Like