Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

'We rarely consider how being highly cultured is a strategy for maintaining power. When leaders are having cocktail parties with influential people, there’s work being done.'

What does it mean for players to win a game? Most games, from Massive Chalice to Civilization, conjure the image of a the player pwning their rivals, ascending to a leadership position, and sitting atop a throne lording over the game world.

But in our real world, where power is not always decided be military might, and geopolitical history has turned on bluffs, personal slights, and ill-fated romances, it’s worth asking if our games sufficiently empower players to think about the true meaning of leadership.

Educator and artist Mary Flanagan explores that question in her game Monarch. Her tabletop game that's played with cards and wooden coins was a finalist at this year’s Indiecade festival, where it garnered as much attention and buzz as bleeding edge Virtual Reality games.

With Monarch, Flanagan aims to show how alternate win conditions can offer a shock to the system for thinking about leadership. Her game imparts valuable lessons that will be of interest to videogame designers as well as tabletop designers.

Mary Flanagan's multimedia works and performance pieces interrogate the central values underpinning game design and play. Digital projects like xyz and [search] examine how players interact with language and search engine association. She also founded the games research lab Tiltfactor in 2003 to explore the design of "humanist" games.

"We rarely consider how being highly cultured is a strategy for maintaining power. When leaders are having cocktail parties with influential people, there’s work being done."

With Monarch, she sought to apply her creative approach to a mode of play enjoyed by friends or families offline, around the dinner table. It's a genre that frequently serves as a foundation for the conventions of strategy game design in video games.

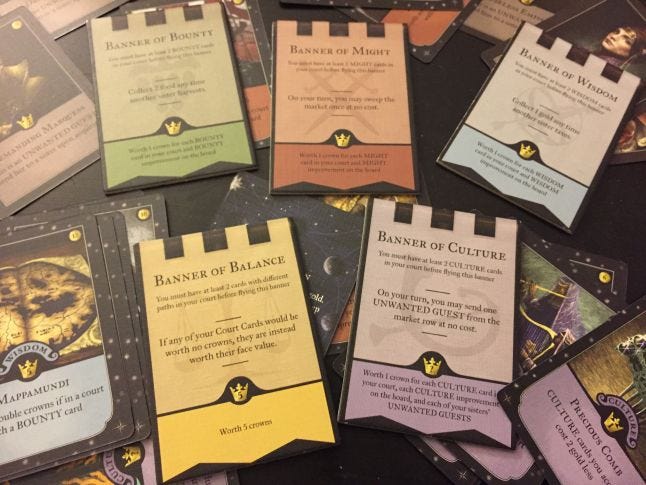

Monarch’s rules are such: As one of four princesses in a fictional kingdom, players must assemble a court worth the highest value by collecting cards and stacking their effects. Cards are purchased from the market with food or gold, which can be acquired once per turn from the land tiles by taxing or harvesting the shared land. The winner ascends to the throne.

There are five defined strategies for victory. Flanagan says that some of those strategies rethink the standard objectives. One strategy, to be “most cultured,” is the biggest shift away from normal strategy win conditions. “We rarely consider how being highly cultured is a strategy for maintaining power,” Flanagan explains. “When leaders in real life are having cocktail parties with influential people, it’s not just for fun. There’s work being done.”

The culture strategy in Monarch revolves around gathering wisdom cards that represent precious artifacts from around the nation, and quickly dispatching “unruly relatives” to other courts to act as negative values against their total score. It’s a more passive plan compared to the more traditional warrior strategy,but it’s a viable path to power that capitalizes on the game’s second untraditional mechanic: the tax system.

The culture strategy in Monarch revolves around gathering wisdom cards that represent precious artifacts from around the nation, and quickly dispatching “unruly relatives” to other courts to act as negative values against their total score. It’s a more passive plan compared to the more traditional warrior strategy,but it’s a viable path to power that capitalizes on the game’s second untraditional mechanic: the tax system.

Tax systems aren't unique in games, but Flanagan's has a special twist. Once per turn, players tax or farm the land. Farming is a no cost action that simply generates food from the shared lands, but taxing claims the gold from the lands only if the player spends food. Unlike the tax systems of many strategy games, Flanagan says it’s a mechanic that implies explicit stewardship and better reflects modern statistics about population happiness.

“Go around the world and ask who the happiest people are, and often they're people in higher-taxed nations,” she says. “Games with normal tax systems that come at some cost to population satisfaction may work for a libertarian view of the world, but it doesn't necessarily work for showing statistical happiness.”

And happiness, again, is valuable to Monarch because the players are not simply in competition with foreign aggressors. They are demonstrating their worthiness to rule the land to their own people.

Flanagan argues that there's an ideological message underlying classic wargaming win conditions, and that that has extended to what we see in most modern games. She is able to rattle off a chain of systems, stretching from 1960’s war games to modern RPGs like Dragon Age, that all have shared DNA in their rulebook design inspired long ago by the output of TSR Hobby Inc.

Flanagan argues that there's an ideological message underlying classic wargaming win conditions, and that that has extended to what we see in most modern games. She is able to rattle off a chain of systems, stretching from 1960’s war games to modern RPGs like Dragon Age, that all have shared DNA in their rulebook design inspired long ago by the output of TSR Hobby Inc.

“When we think about how Game Theory emerged out of the Cold War, compared to new diplomatic models and strategies we don’t see new models from behavioral economics shown in basic economics or political science.”

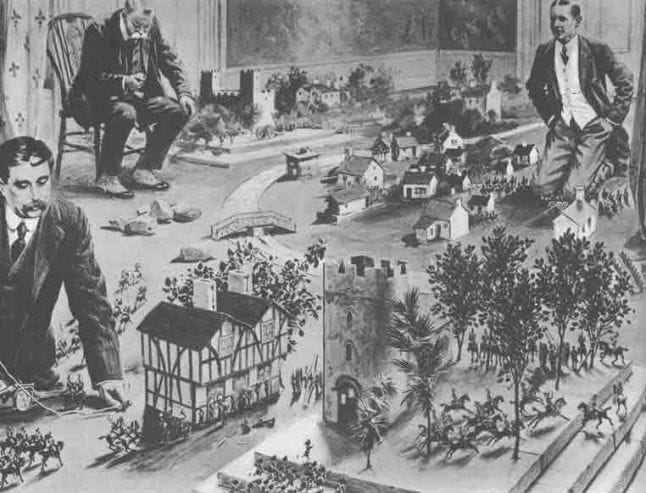

(Right: H.G Wells' 'Little Wars, one of the 20th century's first wargames. Picture via classicwargaming.net)

“So with the rise of TSR Hobby Inc and the way fantasy gaming and role playing games evolved partly from wargaming rules, it's just interesting the way conflicts with dragons and orcs become a reimagining of who we were in conflict with when those games were made.”

In using alternate win conditions and revised taxation systems, Flanagan hopes to make a unique game worthy of family game night. But she has a loftier goal too. She also hopes that players pay more attention to how Monarch and other strategy games express values, and expand their thinking about the kind of world they live in, and how their choices can change that world.

You May Also Like