Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Internet gaming disorder is a very real threat, and the world is starting to take notice. In order to understand this problem, we need to see it from both sides: how the psychology works, and how the game design works.

DSM-V, the official list of psychological disorders, introduced the idea of adding "internet gaming disorder" (hence force referred to as IGD) as a possible classification of mental illness. This seems like a valid move, since being addicted to video games is atypical, stressful, and dysfunctional. However, IGD can't be classified as a simple addiction because it's not primarily neurological, as all substance addictions are. Rather, IGD is an addiction that is intentionally and purposefully created by game designers to keep people playing their games, using psychological methods rather than biological mechanisms. The DSM-V sought to understand IGD in terms of psychology, but first it is necessary to understand IGD in terms of game design. Before labeling IGD as a mental illness and using it as a diagnosis, it's important to understand the principles of game design and how they are applied in the context of internet gaming.

Introduction To Flow

The flow chart.

The flow chart.

In fact, game design revolves around a concept that was originally studied in psychology: Csikszentmihalyi's theory of flow. This effect was studied in fields such as art, sports, and meditation, where people engaged in such activities developed an unnaturally intense concentration on what they were doing. The theory describes three conditions to reach this state: a task with a distinct goal, clear and immediate feedback on one's progress towards that goal, and a reasonable difficulty to accomplish that goal scaling with the person's skill level.

Flow is a key component of games, which are meant to keep players engaged and interested. In order for flow to work, players must get better at the game over time (and consequentially the game must also become more difficult with the player's skill level). Games must through their design enable players to get better at the game, as a prerequisite to allow flow to happen. Thus, game design revolves around teaching players not only how to play the game, but also how to get better at the game, so the game can increase its own difficulty and bring players into a state of flow. The goal of game design is to keep players "in the zone", so game design must act as a tool for teaching skills to players.

However, learning comes to an end. Eventually, a player will reach the point where he understands the game he/she is playing so well that it no longer poses a challenge. A common example is the game tic-tac-toe, which is so simple that after several games, the optimal winning strategy becomes obvious and there is nothing left to learn. At this point, tic-tac-toe is no longer capable of engaging players in flow: referring back to Fig. 1, it becomes a game of control or relaxation because the player's skill level (and the game's difficulty) can't increase any more, and is thus incapable of bringing players into a state of flow. Koster, in his book "A Theory of Fun for Game Design", calls this the point where the game has nothing left to teach and is not worth playing anymore.

Most console games and single-player games are perfectly fine with being put down after completion: they are bought once and experienced, like a movie or a book. However, this becomes a problem with online multiplayer games: they generate their income based on how long people continue playing the game. The world's most popular online video game, "World of Warcraft", gains revenue by charging players a monthly fee to continue playing the game. Many other online games use similar monetization philosophies, relying on the longevity of their game to keep making profits. If players in an online video game reach the point of mastery that Koster described, they would simply stop playing the game, and the game wouldn't make any more money.

The fact that flow has an end is a weakness that console/single-player video games can live with, because of how they are sold. However, online video games can't afford to have an ending, because they need people to continue playing the game. Therefore, online video games cannot use flow, despite flow being the primary method of engaging players and keeping them in the game. Even though online video games can't use flow, they still need some way to keep players interested, or else the players will leave anyway. An online video game needs to fake the sensation of flow and compel people to continue playing the game anyway. This is the root of IGD: the tools that designers use in online video games to keep people playing their games under an artificial guise of engagement.

Operant Conditioning and Fixed Rewards

The psychologist B. F. Skinner was famous for his research in operant conditioning, primarily the Skinner box. A Skinner box was a simple chamber with a lever that would dispense food when depressed. If a rat was placed within a Skinner box, it would eventually press the lever and receive some food. Once this happened often enough, the rat would associate pressing the lever with receiving food.

From a game design point of view, a Skinner box refers to doing something for the sake of getting a reward, rather than because it's engaging. The promise of receiving a positive reinforcement works to motivate people, even if the task they must do is boring. This is precisely why many online video games are designed like Skinner boxes: even if the gameplay is boring (because it cannot use flow), people will still play the game anyway for the reward.

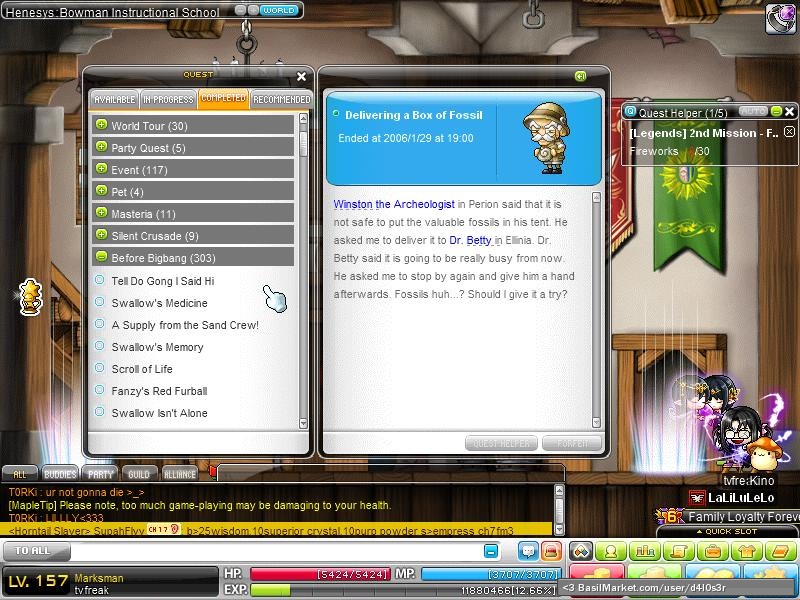

The most common way for online video games to create a human Skinner Box is through leveling systems. A leveling system is one in which a character can accumulate experience points by playing the game. Upon reaching a set number of experience points, that character "levels up," which in its most generalized form means unlocking new content that only becomes accessible once a character has reached a certain level. Accumulating experience points in these kinds of games is a boring process, but players will still go through it because of the promised reward of "leveling up." This fixation on rewards is one aspect of what makes IGD such a threat: players can unknowingly spend hours gathering experience points in an online video game because the game trains them to focus on the reward rather than the process.

Variable Ratio Reward Schedules

A leveling system is an example of a fixed ratio: complete this task, get this many experience points as a reward. However, another aspect of operant conditioning that online game design takes advantage of is the concept of variable ratio reward schedules, where it is uncertain what the reward for a task will be. This concept is most clearly illustrated in the case of casino slot machines, where pulling a lever generates a random amount of money (usually none) as a reward. Variable ratio schedules have been shown to higher response rates than other types of schedules, possibly because of the alluring prospect of an unknown reward. Many online video games also use variable ratio reward schedules to keep people playing.

Nearly all online video games will allow players to find equipment and items, whether through exploring or through defeating enemies or doing other tasks. Finding high-quality items is a positive reinforcement, but there is often no reliable way to earn such items. Instead, there is a low chance to find them randomly. Using a variable ratio system like this in conjunction with fixed ratios like the aforementioned leveling system can create layers of false engagement. Players can become addicted to the thought of winning big rewards without realizing that the "flow" they are feeling does not come from the accomplishment of learning, but rather from the monotony of a routine.

The Zeigarnik Effect and Commitment Compulsion

Various studies have shown that people have a tendency to try to finish what they started, otherwise known as the Zeigarnik effect. This was first studied by Bluma Zeigarnik, when she noticed that waiters at a restaurant would distinctly remember unfinished orders but forget them promptly upon completion. More recently, a 1992 study proved the same effect by interrupting people during their task and asking them to gauge how much time they thought had passed. The effect is even documented in books on how to discreetly influence other people by taking advantage of the natural human desire to complete the tasks they're given. At a glance, the Zeigarnik effect seems like something that would compel people to complete all kinds of video games, and books, and movies, and any other time-based form of entertainment. While this is true, online video games go the extra mile to make intentional design decisions which amplify the Zeigarnik effect and the compulsion for completion.

Many online video games use systems to keep track of tasks that the player must do: collect a certain number of objects, or defeat a certain amount of enemies, or travel to a certain area. Completing such tasks gives the player experience points or rare items, feeding back into the fixed and variable ratio reward schedules described above. However, the fact that games present these short-term tasks to the player takes advantage of the Zeigarnik effect by generating a compulsion to continue playing the game long enough to complete the task. Again, the focus is not on the actual gameplay, but on the psychological mechanisms that compel players to continue playing the game.

Conclusion

There is no denying that IGD is an addiction that truly poses a threat to modern society. However, it would be a massive oversimplification to say that IGD is the same as standard addictions like alcohol or nicotine addiction, because IGD is already so closely tied to theories from not only game design but also psychology. To understand how to approach IGD from a psychological perspective, one must first understand IGD from its own perspective, as we have just done.

What can be done about IGD, considering its full context? Traditional methods of dealing with addiction may help, but the root of the problem is that video games are inherently not supposed to be addicting. Trying to treat IGD as a simple case of addiction would only be a way of accusing video games without truly understanding what they are and why they matter. Games are a powerful form of learning because of how they interact with flow, so psychologists need a better way to deal with IGD other than blocking games out entirely.

Games were never meant to employ psychological tricks the way that online video games use them. At the core, games are about teaching players and engaging them in a state of flow, generating a positive and beneficial experience that they can learn from. Online video games were forced to use psychological tricks because they were unable to use flow, and they were unable to use flow because flow would lead to an end and online games must be endless in order to monetize. The problem is twofold: online video games cannot use flow because they cannot end, and online video games gain income by being endless.

Addressing the monetization issue would be beyond the scope of a psychology paper, but it is possible to address the lack of flow in online video games. IGD happens because the techniques used by game designers to fake the sensation of flow are intentionally addictive, but flow itself is not an addictive experience. This is the reason why gaming addiction is so much more prevalent in online video games than in console/single-player video games: because the former category fakes flow using addiction, whereas the latter category uses flow naturally as a learning tool. If it was possible to use Csikszentmihalyi's flow in an online video game, designers could eliminate the need to rely on psychological tricks and instead make video games that allow players to develop their skills at teamwork, cooperation, and coordination.

The fields of psychology and game design are so closely connected that a problem like IGD must be solved through a combination of the two. If psychologists can come to understand the principles and goals of game design, and designers can come to understand the psychological elements employed in video games, the two fields will be able to find solutions to the problem of IGD.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like