Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild ditches one of the franchise's key design constraints, letting players jump with the press of a button. What does Nintendo's design decision mean?

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild was revealed in detail at E3 earlier this month after two years of near-silence. In many ways, it's a big departure for the venerable franchise. The game features a vast open world, a cooking and crafting system, and over a hundred shrines instead of the standard dungeons.

Given these wholesale changes, another far more fundamental change has been virtually overlooked: in Breath of the Wild, players can make the main character Link jump with a button press. This is something the player could not control in any previous 3D installment, nor in the 2D games (aside from a few offshoot titles or experimental sequels).

This is a big deal.

Why did Nintendo make this momentous decision? And why now? For 30 years, a non-jumping Link has won the day and saved his world time and again. What can we learn about the franchise, and Nintendo's evolving design philosophy, by looking carefully at this simple but under-appreciated new ability?

***

In 1985, Nintendo devised the perfect jump.

When Super Mario Bros. helped launch the Nintendo Entertainment System into the Western hemisphere and relaunch an entire industry, Nintendo's secret weapon was not the powerful blasters of a spaceship or the sharpened blade of an adventuring warrior, but the gratifying feel of a well-timed leap.

Mario’s jump was and is the perfect cocktail of momentum and gravity. He soared across chasms with fantastical agility, yet something about his humble attire and optimistically raised fist made the act feel human. Players could steer him in mid-air and subtly guide his plummet back to the ground, which made the result feel earned. It was this simple satisfaction over all others that made Super Mario Bros. so epochal. (After all, Mario was once known simply as Jumpman.)

After perfecting this most repeatable of actions, which fast became the crux of so much movement in these new digital worlds, you’d think Nintendo would do what they normally do: iterate, evolve, amplify, polish. Surely their next major character would make Mario’s jumping look pedestrian.

In 1986, Mario’s inventor Shigeru Miyamoto introduced his next great hero, Link. He was on a quest to save the world with a wealth of tools and weapons.

But there was one thing he couldn’t do: jump.

The Legend of Zelda employed a top-down perspective; towns and fields were essentially two-dimensional grids. There was no height to ascend, no boulders to hop over. His lack of ups made sense.

The quirky Zelda II: The Adventure of Link gave the player a jump button, but only in the side-scrolling action scenes. The move felt different than Mario’s; this was not a vehicle for boundless joy but one weighted down and cursory, an opening for punishment, a means with no end.

The choice to add Jump to Zelda II became an anomaly rather than a rule. That game’s follow-up, A Link to the Past in 1992, reverted to the an overhead view and, thus, a grounded, earthbound character.

With the franchise’s shift into three dimensions for 1998’s N64 entry, Ocarina of Time, a newly agile Link galavanting through a fully realized Hyrule would need increased mobility. How could one save a kingdom from evil if they couldn’t even leave their feet on purpose?

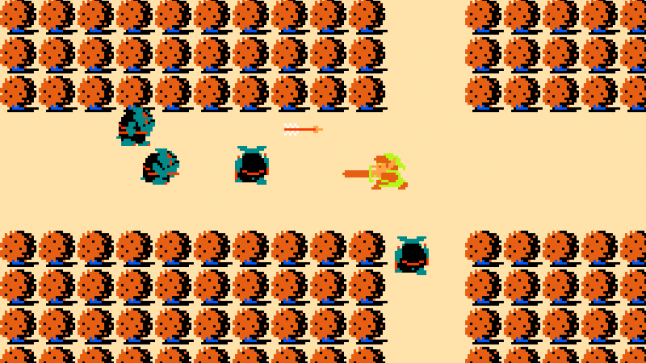

Before The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild,

jumping happened automatically in 3D Zelda games.

Nintendo held their ground; Link could swing a sword and toss a bomb, but none of the thirteen buttons on the N64’s trident controller allowed you to jump. Why is this?

Chris Kohler, author of "Power-Up: How Japanese Games Gave the World an Extra Life," speculates that Nintedo's reluctance to let its hero leave the ground may have been motivated by a desire to distinguish the game from their other flagship franchise. “Originally, Nintendo removed player-controlled jumping from Ocarina of Time so that the game, which otherwise played very similarly to Super Mario 64 in terms of being a free-camera, third-person action-based title, would be distinguished from Mario,” Kohler tells Gamasutra. “If Link could jump, wouldn't they do all sorts of jumping puzzles in the game? Then it would have felt like Mario, not Zelda.”

Video games often have odd rules that we accept for little reason--e.g. if an anthropomorphic egg chases you, shoot him with pepper--but a somewhat realistic person running around a forest should be able to hop up and down if he wants. The remarkable thing is: Nintendo was right.

Jumping was not verboten in Ocarina of Time; it was merely a scripted behavior, your free will taken away in the spirit of simplicity. You ran toward the edge of a bridge or cliff and Link automatically made the leap. For such a complicated world, your locomotion through it was designed to be efficient; each step had a function.

The game was a class act of world design, one giant puzzle you solved across acres and decades. Ocarina of Time not only set a benchmark but created a mold that would stand the test of time, offering developers a template on which to design their 3D Zelda adventures for years to come. Nineteen, to be exact.

***

After a vague glimpse at E3 2014 and several delays, Nintendo fully unveiled the latest game in the Zelda franchise last week. We learned its telling subtitle, Breath of the Wild, and that it would be released in 2017 alongside their still-secret new console codenamed NX.

What we saw confirmed the extent of their efforts and why this game has been cooking so long: Hyrule is no longer the patchwork of eight separate locations stitched together, but an expansive world replete with crumbling towers, craggy cliffs, and untold secrets. To maneuver through all this space, Nintendo and Monolith Soft, makers of Xenoblade Chronicles X that's sharing development tasks, decided to finally take the anchor off Link’s ankles. The player can leap and bound across fields as they wish.

In prevous games, Link always relied on items to aid him in his quest: A hookshot to propel him over great distances, a Deku Leaf to allow him to glide, or a scepter to move the wind. He walked, or ran, or rolled. He rode on creatures--Epona the horse, or a lion-headed talking boat, or a giant bird. In Breath of the Wild, his horse returns. But the landscape is larger and more vertical than ever before. For this new Hyrule, Link could not merely roll around and crash into pots.

The choice to abandon traditional constraints and let the player jump at will may seem tiny. If you can get where you’re going, the ultimate result is the same, right? But developers especially know that how one traverse a gameworld is of the utmost importance.

***

Change can be ruinous. Cast your memory back to Pac-Mania (1987), a pseudo-3D interpretation of the arcade classic that let Mr. Pac do the unthinkable: Jump over ghosts. There's a reason the game has faded into obscurity--in tweaking the formula, the magic was gone.

But repeating a formula to the point of stagnancy can be just as problematic. The Legend of Zelda franchise may have written the 3D Adventure blueprint in 1998, but it's been re-written countless times since then. Ubisoft's protagonists in the Prince of Persia and Assassin's Creed games have the acrobatic prowess of Cirque de Soliel performers. Player agency lies at the center of Bethesda's Elder Scrolls and Fallout games; with their massive worlds, uncountable baubles and addictive side-quests, jumping doesn't always help you progress but it's there anyway. Players have come to expect it.

In a lot of ways, Breath of the Wild feels like a capitulation to the realities of the marketplace. This is what 21st century players seem to want: the added agency over character movement, the crafting, the giant map, the customizable experience.

Many who played the demo at E3 were rapturous. Somehow, by aping modern tropes and bowing to convention, Nintendo has made Zelda feel fresh again.

One only hopes they didn't bend too far.

***

Nintendo’s reluctance to offer traditional control often comes with an asterisk: “We’ve proven we know what we’re doing.” Link can’t jump in Ocarina? Then he won’t need to in Majora’s Mask or The Wind Waker or Twilight Princess (or numerous handheld sequels) either. The willingness to strip things down and leave out what players have come to expect has certainly succeeded for the company's other franchises. A tennis match where you can’t move the characters around the court? That's less freedom of movement than players were afforded by Pong! And yet Wii Sports arrived, stripped down and laser-focused on the racket swing alone, and became one of the best-selling games of all time.

We think we want limitless opportunity. But too much freedom breeds indecision; choice breeds paralysis. Constraints create context--one thing next to another thing has meaning whereas a thousand things in a pile is indecipherable.

Nintendo is calling Breath of the Wild an “open-air” game, ignoring the industry-standard “open-world” nomenclature. That sounds like a lot of freedom. With Zelda, Nintendo is used to crafting exquisite machines that appear to be organic. You can craft a world. With air, you can only breathe in and breathe out. Jump from high enough and you might even hold your breath.

At one point in the history of game design, “Jumping” was indeed a revolutionary idea. The original Jumpman gave Donkey Kong an edge against its arcade forbears. That same year, Jump Bug showed players the very first side-scrolling levels, your buggy jumping over the terrain surging towards you. But in 2016, the act is obvious and expected, like crouching behind a crate or foraging a corpse for ammo.

We don't know all the ways that Nintendo plans to make this most mundane of behaviors figure into the central adventure. But we can be reasonably certain of one way that players might choose to use it. Kohler suspects that many will simply jump and jump and jump as they wander around in the new game, just as they rolled and rolled and rolled around in previous installments. It's a way to occupy yourself while you get around.

“I'm sure it's no coincidence that you could roll in the earlier Zelda games, and that many players chose to do it all the time,” he observes. “You've just got to have something to do. I think they would have done it even if rolling wasn't faster than running. Jumping in the new game is like that.”

You May Also Like