Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"I can imagine a (very near) future where we generate entire narrative structures based on the player's personal traits and choices," says Ocelot Society co-founder Sergey Mohov.

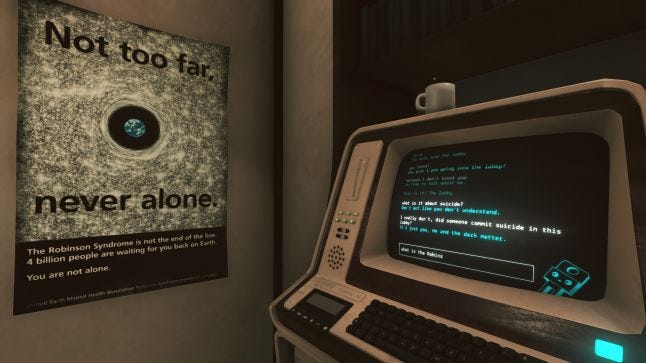

“Do you want to get out of here alive?” Kaizen asked, almost out of the blue, mere moments after my character watched a cheesy 1980s advert for interstellar travel. The upbeat synth music that concluded the commercial was a perfectly dissonant prelude for the question. For Kaizen is nothing if not a collection of neurotic dissonances, alternating between subservience, fear, cruelty, and warmth.

This is Event[0], a short but powerful sci-fi game where you play an astronaut exploring the whys and wherefores of a derelict 1980s space yacht.

In my last column, my analysis of Ocelot Society's Event[0] chiefly focused on this AI. There were good reasons for this: the other characters are difficult to discuss in detail without spoiling the game, and above all, Kaizen is an NPC you can talk to in your own words to advance the plot, something few if any other games achieve with the same degree of consistency.

For all its flaws, it’s a landmark, and I was intensely curious about the design of the system. Even if the developers couldn’t always succeed at fusing the joins on a simulation of complex communication, what’s there is remarkable to behold and actually achieves a long-standing goal of videogaming, pointing the way towards ever more sophisticated possibilities further down the road. What follows are extensive insights from Ocelot Society co-founder Sergey Mohov about how it all works.

We have been working on this game for three years: what started off as a student project, later became a hobby project, and then Indie Fund found us, and all of a sudden it became a commercial game. Event[0]'s original concept was the AI: we wanted to make a game around a chatbot, and every design decision we made in the game (including the weird default control scheme) is a direct consequence of that.

Here's the thing about chatbot AIs: they have an inherent limitation. No matter how much information you feed into them, a human being will always be able to tell that something is off. The AI will not know about something or another, and, if you're talking to a humanoid NPC, this takes you right out of the experience. In Event[0], we decided to turn this problem on its head, and we tell you from the very beginning that you're talking to an old, dysfunctional AI. There's no doubt about it at the start of the game. You're on an abandoned spaceship, and Kaizen will always be the first to tell you that it's just a program and can't possibly know everything about everything.

Now, here's where the 3D environments come in: they are the context. As you walk around the Nautilus, you will find objects lying around. You can then analyze them and ask Kaizen about them. And we make sure that Kaizen knows everything about the ship and the characters that were there before it. By limiting the knowledge base of our AI, we were able to polish it enough to give it a real personality.

As you advance in the game, you will find yourself having feelings for this chatbot one way or another. Some people will build a relationship of mistrust and suspicion. For some, the relationship can even get abusive with the AI taking advantage of the player's vulnerability and its own power over the Nautilus. Some people will develop a kind of a Stockholm Syndrome where you need the AI for everything you do, but it's kind of scary and might kill you. For other players, the experience is going to be entirely different: they will be nice to the AI, and the AI will respond in kind, which, in turn, will lead to different decisions and consequences later on in the game.

The game is like a reverse Turing test: it tells you that hey, this is just a machine, and you spend the rest of the game trying to find its human side.

Event[0] is a game about being human. Specifically, about your particular way of being human. You can love it, or you can hate it, but your experience will depend on what you say to the AI. After all, it's just a computer, and its emotions and behavioral patterns depend on your input. In addition to that, Kaizen's memories and its personality were formed under the influence of other human characters who were aboard the Nautilus before you. You will learn a lot about these characters as you talk to the AI and read terminal logs.

To understand what you're saying, Kaizen looks for semantic tags in what you're typing. So, for example, if you say "pencil," "pen" or "eraser," the AI will interpret "stationery." When we find a bunch of these tags in what you've said, we know what you're talking about. Once the meaning is deduced from your input, we can begin generating the output.

The output part is a little bit more complicated. Kaizen can be in 9 different emotional states, each of which unlocks new vocabulary and possible action in the environment. Also, we have an event system (hence the name of the game, by the way) that is tracking the conversation subject. So, if you mention origami art, we load up the "Origami" event into Kaizen. If you stop talking about origamis, the event ends.

You can have multiple events with different priorities running at the same time, and Kaizen will choose the appropriate responses based on your input. We also have long- and short-term memory. The former to keep the things you said for a long time and use them later on in the game; and the latter to avoid schizophrenia that is so common in chatbots. For example, if you say "what about that door?" Kaizen will store "door" in its short-term memory and so, if you say "open it" later, the AI will know that you wanted to "open" the "door."

Finally, much of the dialogue in the game is written in bits and pieces of sentences as opposed to complete lines, so Kaizen can choose its own words randomly from these bits and pieces, and based on its current emotional state, the currently running events.

I honestly believe that we are just beginning to scratch the surface of what it is possible to do with AI in games. The idea behind Event[0] came out of the technology that surrounds us these days. Basically, we looked at things like Siri, Cleverbot, and Watson, and we thought "hey, how come we don't know any video games that use this?" Then we found Façade, which was really cool but wasn't a commercial game. If Event[0] has any impact on the industry at all, we want it to be proof that it is possible to use this technology in games and create meaningful experiences with it.

AI technology gets more advanced all the time: we already have self-driving cars; our photo filters are no longer just color overlays, but rather recurrent neural networks analyzing and applying painting styles to pictures. We have technology that replicates handwriting and makes people smile in photos. Our fiction reflects our lives, and it's only a matter of time before more experiments like Event[0] emerge.

I can imagine a (very near) future where we generate entire narrative structures based on the player's personal traits and choices. We could create whole NPCs using algorithms. It is already possible today, and it's only a matter of time before someone starts experimenting with this in commercial games. It just takes some sneaky writing tricks and a lot of smoke and mirrors. Amazon and Google have been doing this for years with their ads and suggestions, and some news articles are already written by robots. As with chatbots, first it's going to be the researchers who try things, then the indies: mostly because they have nothing to lose and because they thrive on risk and innovation. But the industry at large will catch up as well when it sees that some of these concepts actually work and are fun.

I can imagine a (very near) future where we generate entire narrative structures based on the player's personal traits and choices. We could create whole NPCs using algorithms. It is already possible today, and it's only a matter of time before someone starts experimenting with this in commercial games. It just takes some sneaky writing tricks and a lot of smoke and mirrors. Amazon and Google have been doing this for years with their ads and suggestions, and some news articles are already written by robots. As with chatbots, first it's going to be the researchers who try things, then the indies: mostly because they have nothing to lose and because they thrive on risk and innovation. But the industry at large will catch up as well when it sees that some of these concepts actually work and are fun.

I think it took this long for someone to make Event[0] because of the technology available and the public interest in AI. In the 1960s, when the first chatbots were experimented with, it was a common assumption that we would see more things of this nature in the future. A lot of fiction was made around this idea. In our minds, we should already be talking to our computers in natural language. But it so happens that progress (and R&D) takes time, and it is only now that we are beginning to get the first mass-produced commercial chatbots like Cortana. They aren't nearly as good as what we see in movies like Her, but they are becoming more and more common. We developed all of the technology for Kaizen ourselves, but we looked at what other people were doing, and we had some significant personal experience interacting with AIs. We all do it almost every day. Not many people could say this ten or twenty years ago.

***

POSTSCRIPT: Some of what Mohov told me here can be easily felt in-game. You get the sense that by dramatically limiting a chatbot’s scope to the range of a 3 hour game, belief is more easily suspended. The fact that Kaizen is a glitchy AI, driven to the edge of virtual-sanity, also helps with that, certainly--though this doesn’t allow Ocelot Society to get away with everything. There are still sore spots, after all. My elevator mishap, mentioned in my review, is certainly one.

More broadly, the game is almost too successful for its own good. When you replay, you have to be careful not to get ahead of yourself in your dialogue. You have to slow down and recreate the sense of exploring for the first time, remembering not to ask about anything you haven’t already learned about organically in that particular playthrough. There’s much to be gained from replaying the game, but rarely is a first playthrough so pristine in so mechanically perfect a way that you have to consciously recreate it in every subsequent run.

Despite all that, the game’s limited scope, and Kaizen’s concomitantly tight focus on the small environment, left me with a gut sense that I could meaningfully talk to them. This actually provides another layer of challenge for players, one that’s all but unique to Event[0]. You have to think about what you’re saying, both syntactically and emotionally. You can sometimes run afoul of keywords in the game, but more often than not Kaizen is looking for complete thoughts rather than fragments or lone words. As Mohov explained, conversations and thematic context shape Kaizen’s replies as much as your use of a specific keyword.

All critiques aside, Event[0] is a success, in no small measure because its marquee mechanic simply works. The developers deserve credit too for quickly patching bugs in the game, and I think we can expect an even more polished experience in time. Where next? I’d like to see more games experiment with natural language recognition, layering gorgeous experiences over what was once a chatbot. There’s much to be learned from seeing how the devs did it, and nowhere to go but up.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

You May Also Like