Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Secret Games Company's new game Kim is, like The Witcher 3, an open-world RPG based on a book of the same name. The similarities end there; SGC's Jeremy Hogan explains how (and why) Kim was made.

The Secret Games Company's new game Kim and CD Projekt Red's 2015 hit The Witcher 3 share something in common: Both are open-world RPGs based on books of the same name.

What's interesting here is that while CDPR's Witcher games are based on a relatively recent (think '80s) series of cult classic pulp fantasy novels, Kim can trace its literary origins back much farther, to the 1900-1901 publication of Rudyard Kipling's classic novel of the same name.

If you've never read Kim, know that it's widely regarded as the greatest work of a Nobel Prize-winning author. Set in India in the late 1800s, the novel recounts the tale of an orphaned beggar who meets interesting people and has a series of adventures as he learns the ins and outs of politics, spycraft and spirituality.

So how do you make a game out of that? More intriguingly, why would you try and make a game about a beloved literary work, one that portrays India still operating beneath the weight of British rule?

To find out, we briefly corresponded with SGC founder Jeremy Hogan ahead of Kim's release out of Early Access today.

Hogan: Above all, the book itself. It’s a beautifully-written, rollicking adventure with a wonderful cast of characters in an exotic but believable world. The Guardian named it one of the 100 best novels ever written; it was given special mention at the presentation of Rudyard Kipling’s Nobel prize and explorer Wilfred Thesiger described it as “the only book of prose that I can open at random, at any page, and read with the same delight as if it were poetry.”

I love that quote because I feel exactly the same way. Kipling was a virtuoso writer and this is his masterpiece but his reputation today, however justified, has meant his work has slipped a little from the public consciousness. All of which made Kim an irresistible subject for an indie team like ours, who wanted to offer players something truly different.

We’re a core team of 3, an artist, a programmer and myself with help from a few contractors along the way. We’re using Unity and began development at the end of 2014. It’s been a fantastic project – without doubt, my proudest achievement to date and the most fun I’ve had making games.

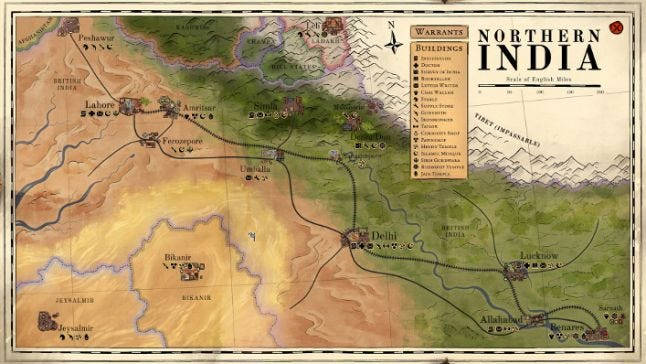

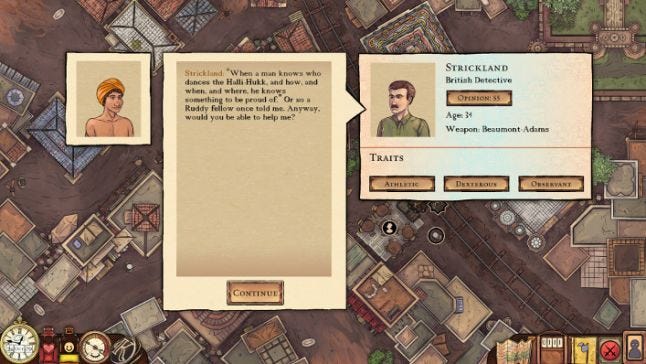

The biggest challenge has been the sheer amount of work for such a small team. Kim may be 2D and relatively accessible but it is not small. There are 500 levels including 17 hand-painted towns based on their historical counterparts. It has a huge cast of characters and hundreds of branching conversations to have with them, most of which use dialogue from the book and from Kipling’s many short stories set in India.

We ran a successful Kickstarter for our first game, Dreaming Spires, a board game about the history of Oxford University and the great men and women, who studied there. Once Kim was in a playable state at the end of last year, we thought a Kickstarter would help us spread the word and hopefully attract some early players.

We still had a lot of new content, polish and iteration to get through and we didn’t want to get distracted or compromise our vision for the game so we didn’t offer stretch goals or extra rewards, which probably hurt our campaign total, but it served our purposes well.

I think that’s absolutely right, our games look like games and we want them to feel like games too. I was brought up on board games and strategy titles like Civilization. Rise: Battle Lines was originally paper-prototyped and is effectively a board game whose simultaneous turns and complex computation mean it can only exist digitally.

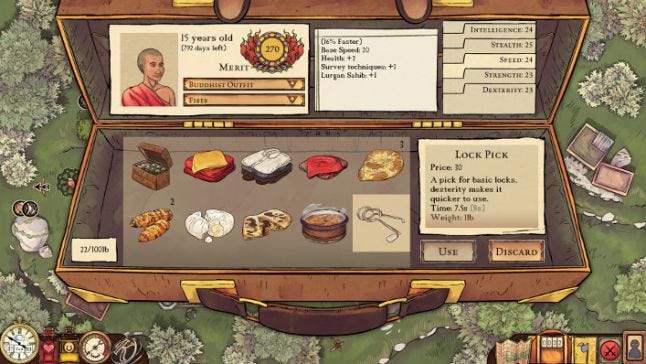

In Kim, the player’s relationship to the character is similar to their role in Civilization; they are the all-seeing eye in the sky, piloting Kim through his coming of age – the author of their own version of this classic story. Their controls are inspired by the era, we wanted each UI element to feel like a Victorian object so it squeaks and scratches and clunks as it animates and lights up. Kim’s inventory is stored in a battered leather suitcase, his objectives are in a traveller’s notebook, the game’s map is straight out of National Geographic and whenever time passes, the pages of an unseen book turn by.

I was certainly concerned about how to represent British India but also excited to present a setting, which is so interesting and comparatively under-explored.

We’ve done a lot of research and been really careful not to lionize or whitewash British imperialism; we never shy away from representing its ugly sides. The book lends itself to this, it’s a love letter to India: its people, its religions, its food, its nature, and it mocks the pompous imperialists, who couldn’t understand it. I was reassured by how popular the book is in both India and Pakistan, where it is taught in schools and considered part of their literary heritage.

As Brits, we don’t have to like our history but we can’t ignore it, we should learn from it.

You May Also Like