Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

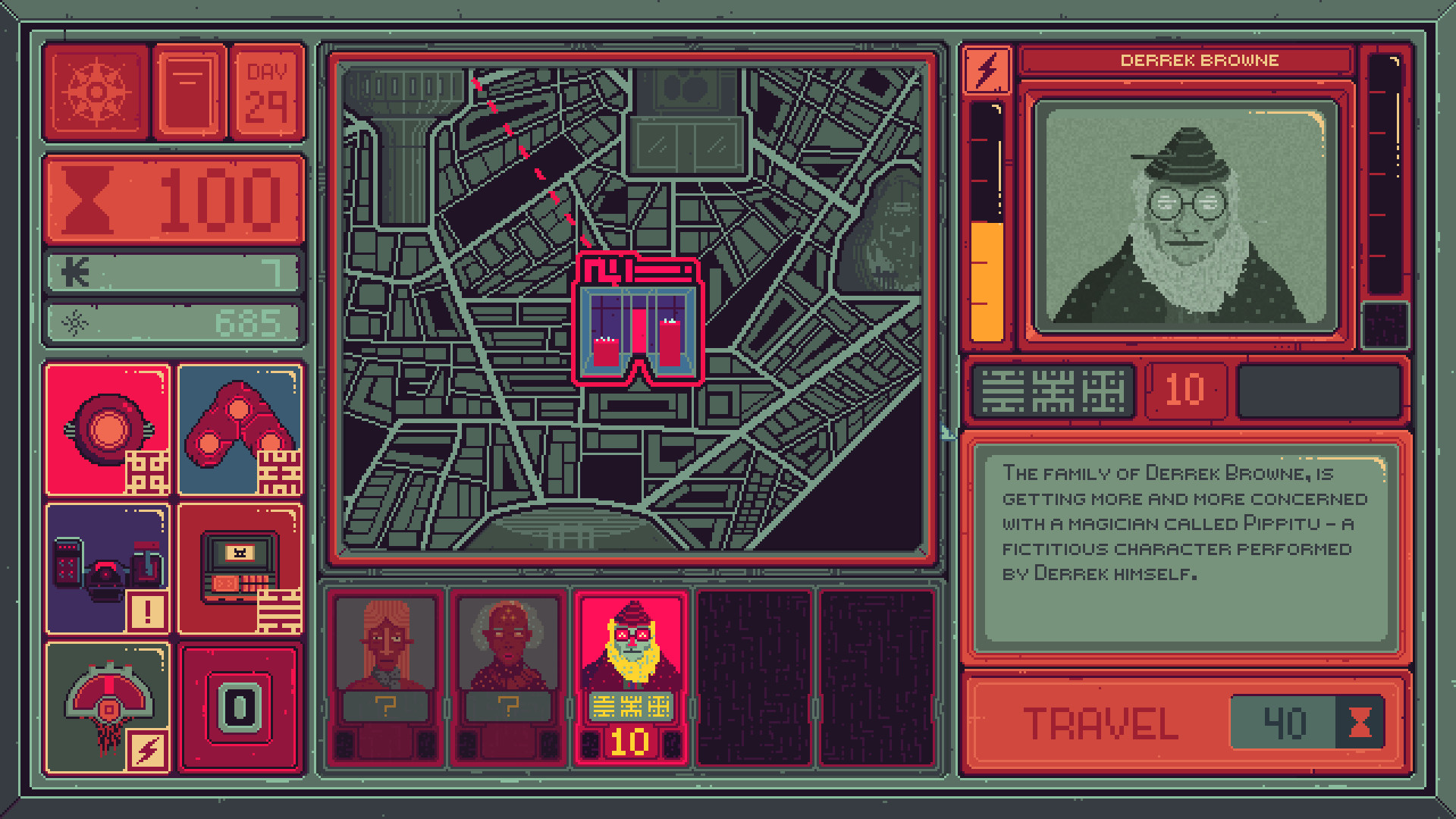

Mind Scanners is a retro-futuristic psychiatry simulation in which you diagnose the citizens of a dystopian metropolis. We caught up with Malte Burup, game director on Mind Scanners, to discuss game design choices behind his quirky Orwellian brainchild.

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on May 28, 2021

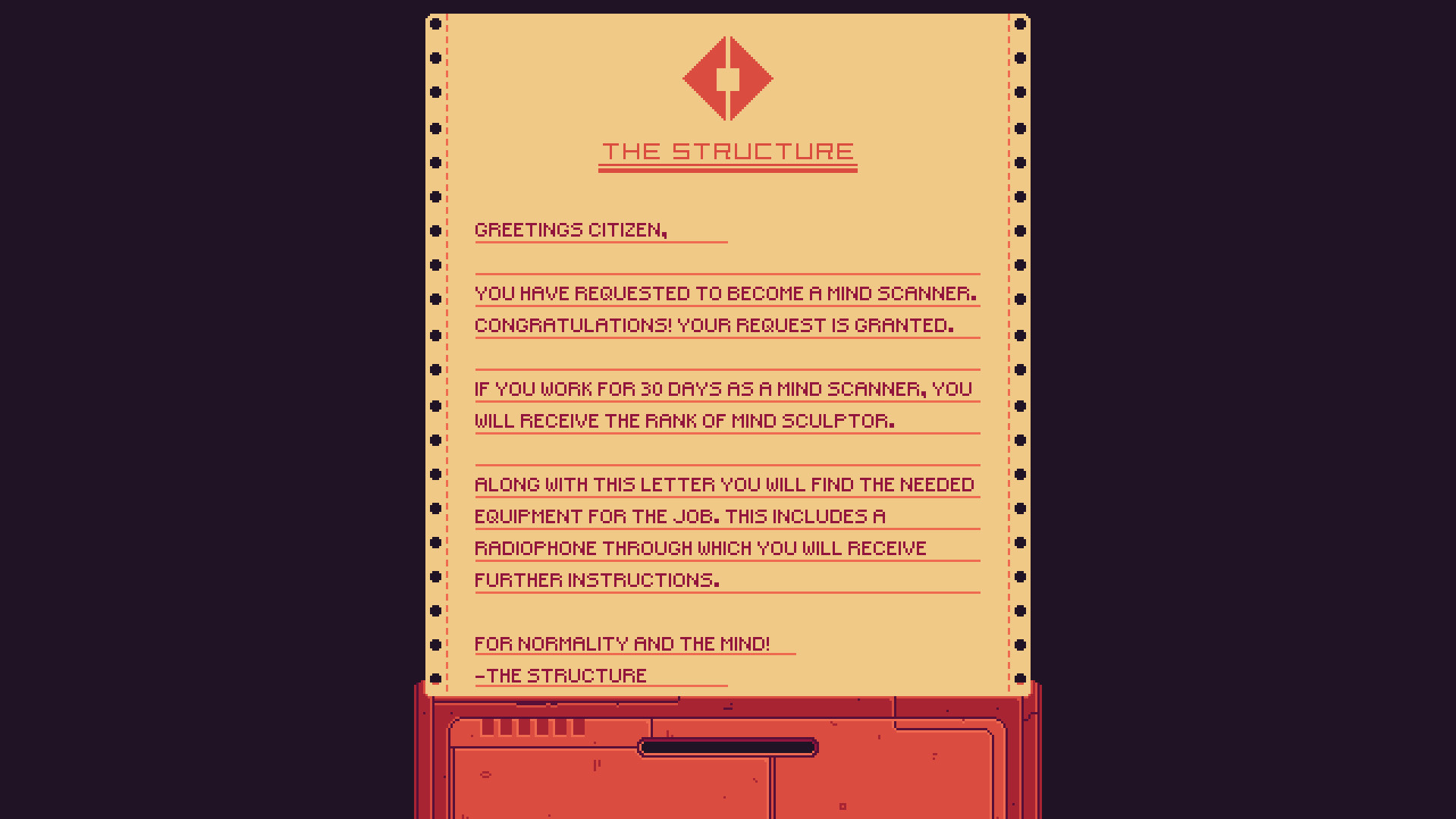

Mind Scanners is a retro-futuristic psychiatry simulation in which you diagnose the citizens of a dystopian metropolis. There’s a bigger story unfolding, too, that can see the player pledge loyalty to the regime of The Structure or team up with a rebel group known as Moonrise. The game developed by The Outer Zone, a small indie studio from Copenhagen, Denmark, and published by Brave at Night (makers of Yes, Your Grace), came out on May 20.

On May 25, we caught up with Malte Burup, game director on Mind Scanners, to discuss game design choices behind his quirky Orwellian brainchild.

Malte Burup, game director on Mind Scanners, founder of The Outer Zone

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Malte, let’s start with a couple of words about yourself and the studio behind Mind Scanners?

My background is art, but I also did game design, writing and sound design for Mind Scanners. I released a couple of smaller games through my company The Outer Zone, including a point-and-click series called Tales From The Outer Zone set in the same world as Mind Scanners.

So, I made up the concept of the game, but I had help from programmer Jesper Halfter for the initial prototype. Then Rasmus Nilsson joined me for the creation of the vertical slice demo and [we worked together — Ed.] onwards. Other people, too, have helped me out along the way, so I have only been alone on the project for shorter periods of time.

Early into development, the title was called House of Lunacy (and before that – Doctor Kiefer’s House of Lunacy) and featured a far grittier aesthetic. All the minigames were different. Could you tell us what has survived of that version in the final edition? And why have you completely redesigned your original build?

My initial idea was inspired by a visit to Museum Dr. Guislain in Gent, Belgium – an old mental asylum turned into a museum about the history of psychiatry. Learning how we have changed our definition of mental illnesses throughout history and how we have sought for new ways to cure the mind – these things got me thinking. What is normal? When is the mind sick? Who gets to decide?

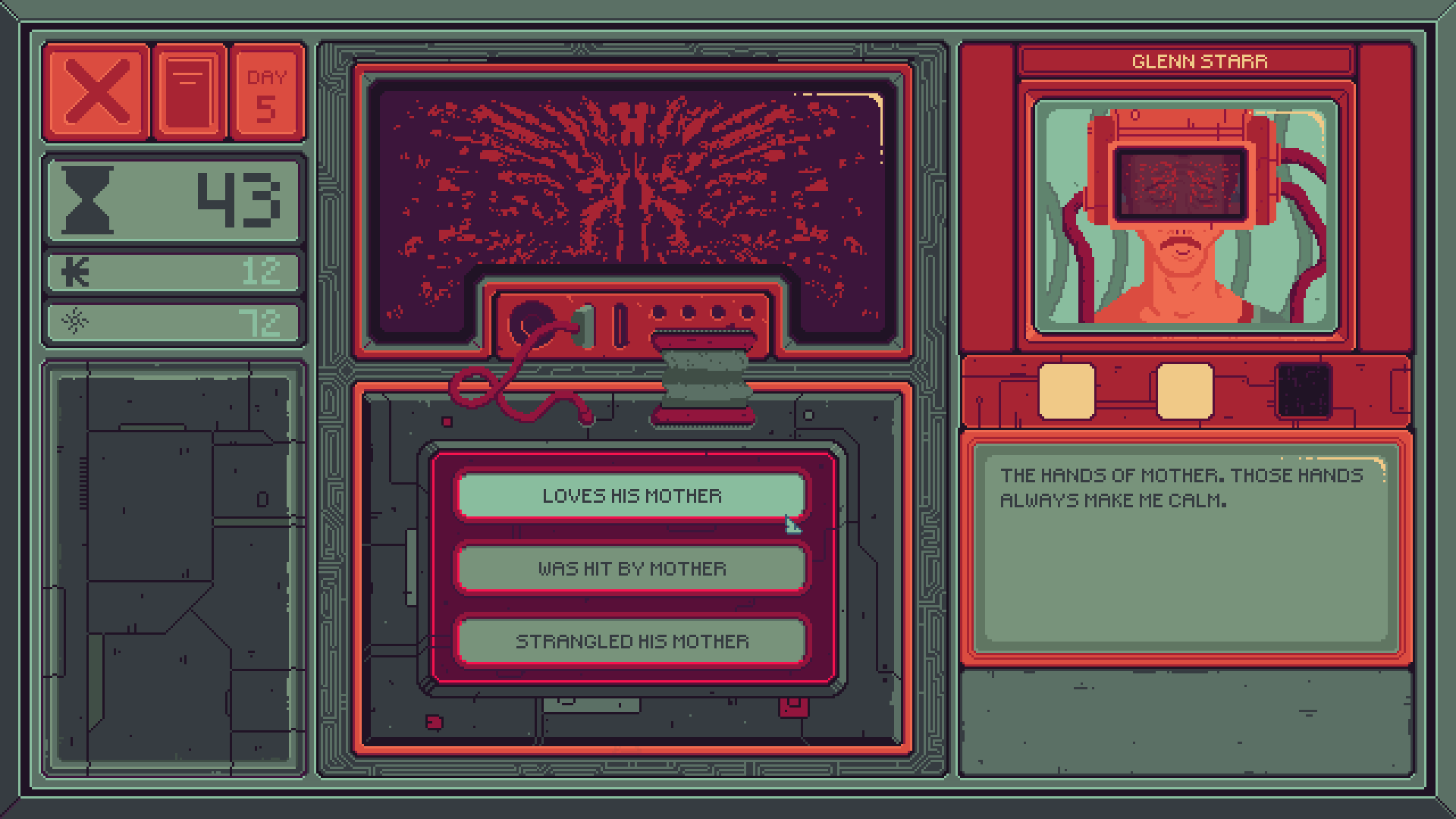

“Mind Scan” mechanic from Mind Scanners

Then I realized it would be a perfect theme for a game.

What makes games stand out from other mediums is interactivity. A game designer places responsibility into the hands of the player. By letting the player assume the role of the Mind Scanner, we can ask the player these questions. And by making the player face ethical dilemmas and difficult moral choices, we might encourage them to reflect on these problems.

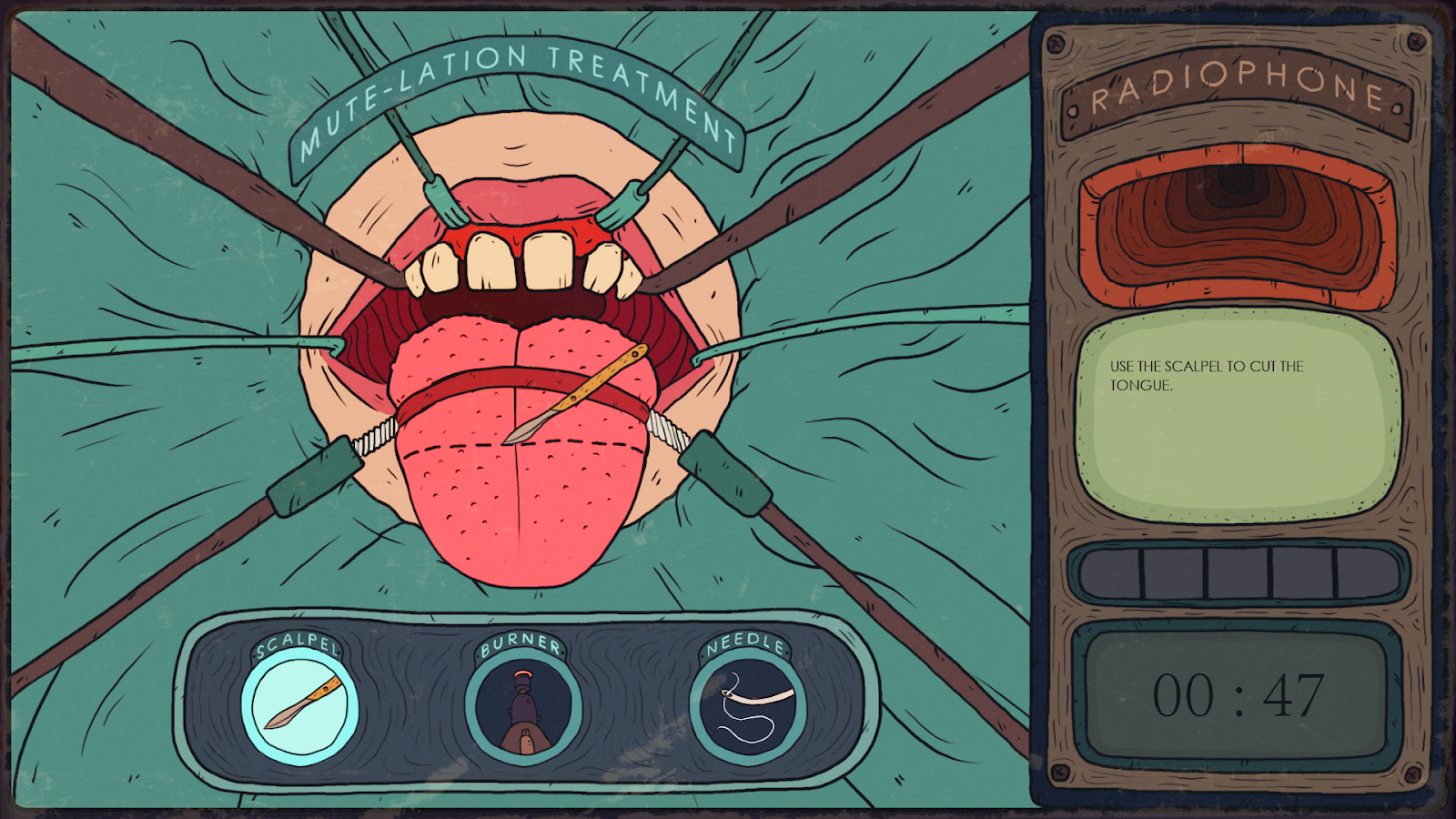

At the museum, hearing about the grotesque and often brutal treatments of the past was disturbing, and something I could not shake off. So when I designed the treatments of the old prototype, I wanted to underline the terrible treatments of the 1800s by emphasizing the grotesque. The game became way too dark, gritty and violent for my taste, so I started over.

UI and mechanics from the early prototype

I felt that the game needed a lighter, more colorful, humoristic and surreal tone, to make it easier to digest, but also to state that Mind Scanners is a game, that it’s not real therapy and it’s historically incorrect.

The main concept survived the transition, along with some words and ideas, but it feels like a completely different game.

I have to mention that there also was another prototype set on a ship. In retrospect, would you say that you should have discarded various prototypes quicker – without committing too much effort to each of them?

Yeah, definitely. I worked much faster after the first couple of prototypes. Early on, though, I wanted to try different things out. My strategy was to try out all versions and then pick the best one. Turned out to be a bit overkill. As you mention, one of the versions was on a ship — a cool idea, but completely beside the point.

Back in 2018, you mentioned on your blog that your being an artist sometimes stands in the way of your being a game designer. Like you get too carried away by the story and the ideas and tend to neglect the gameplay itself. I wonder if you still feel that way?

I think so, yes. I still get “great” game ideas, and after a day or two, I realize that it’s not a game, but a scene from a movie, or just a feeling. These glimpses can be used in a game for sure, but they are not games themselves. Forcing a game design onto an aesthetic does not always work. With Mind Scanners it was more a case of forcing a game design onto a theme/concept. And this has, by far, been the most complicated thing about this project. Working with the human mind is a gray zone. By contrast, game design rules need to be clearly defined. The clash is tremendous, and building gameplay from this has been quite difficult but also quite the eye opener. For my next game, I will start with game design for sure and build a world around it.

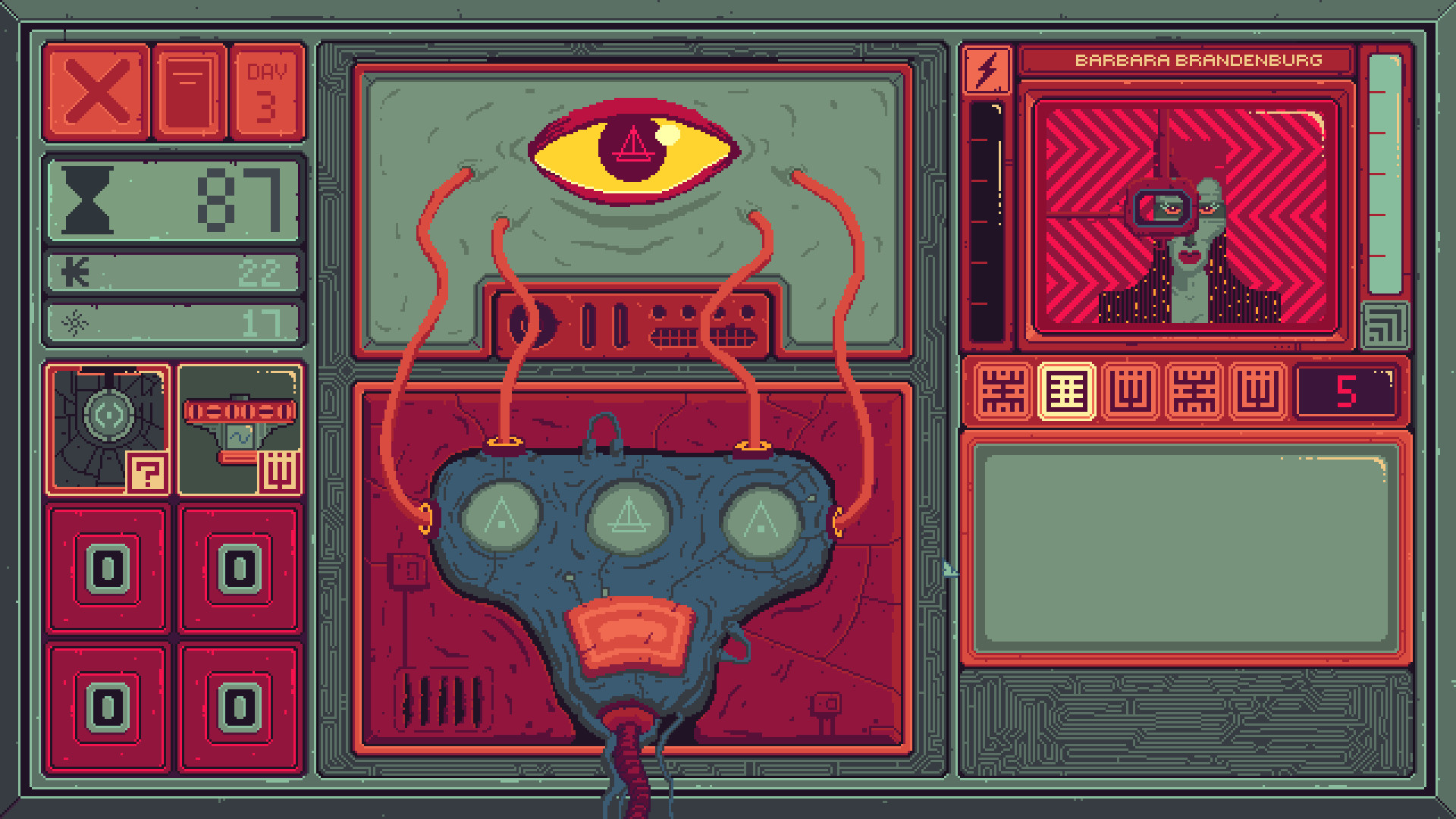

UI and mechanics from Mind Scanners

Creativity aside, you also mention on your blog that the original build was funded by a cultural grant from The Danish Film Institute. You also managed to secure funding from The Danish Arts Foundation to do the overhaul of Mind Scanners. When you submitted your game to those foundations, how did you pitch it in a way that highlighted the game’s cultural relevance?

I focused mostly on the ethical dilemmas that can occur within psychiatry and how it is important to keep discussing mental health and reflect on both the positive and negative sides of our mental health system. I explained how a game can do just that, by placing the responsibility and judgement in the hands of the player.

Ultimately, the game was published by Brave at Night. A lot of devs I talked to say how they always carefully study a publisher’s portfolio before signing with them. Brave at Night had previously published zero games. In fact, they are a development studio, whose only game Yes, Your Grace was published by No More Robots. How did you hook up with them? Were you concerned about the lack of the publishing experience on their part?

We had our demo, and were out looking for a small or medium-sized publisher that wanted to publish a small niche game. We needed money to cover half of the production cost. One day, I retweeted Yes, Your Grace, as I thought it looked like my kind of game, and when I checked my inbox, Brave At Night had contacted me! Their game is similar to Mind Scanners and seeing how well it was received, I thought, hey let’s try this publisher. The good thing about Mind Scanners being their first published title is that we didn’t need to worry about them focusing on other titles and forgetting about us, something I’ve heard can happen with bigger publishers. It turned out to be the best collaboration, and they have done a great job in marketing Mind Scanners at a low cost.

So you have this beautifully weird psychotherapy simulator inspired by the barbaric medical practices of yore. But would you say that the game offers a somewhat reductionist view of modern psychotherapy? They no longer subject patients to electric shock or submerge them in water, right?

Actually, electroshock therapy is still used as a treatment today — and water therapy is still used as well in alternative medicine.

Oh.

Today, psychiatry as a whole is much more refined, of course. It’s important to say that in general, mental healthcare is a good thing and psychiatrists around the world are doing their best to take good care of people struggling with mental illnesses. Mind Scanners, though, boils down diagnosis to a simple “sane” or “insane” stamp and reduces the complexity of psychotherapy to the push of a button. This is not, and never will be, how it works in reality. It is an attempt to translate this very complex thing into a set of mechanics.

As I mentioned earlier, this is exactly why the game was so difficult to design. And this is also why we chose to move the setting from the past and into a science fiction world separated from our time and place. In science fiction, you can do anything. So the only way we could turn psychiatry into clearly defined gameplay was to place the game in a fictional sci-fi world where it is possible to manipulate the mind in any way.

The absurdity of this reduced version of psychiatry also helps underline the harsh and heartless methods of the dystopian regime, The Structure.

Even though Mind Scanners is purely fictional, we still try to reflect on the problematic parts of psychiatry such as medical errors, lack of resources, misdiagnosis, restraints, force, overuse of drugs, labeling etc.

But why this surreal world?

I wanted the world to feel very different to ours, while still resembling a “real” world. The weird choice of colors, the strange machines and the made-up words all makes it feel otherworldly, while the pixel art and sound design makes it feel like a game.

Speaking of the made-up words. In the world of Mind Scanners, there’s a power source called “Zygnoka” and the currency called “₭apok”. Any particular significance behind these words?

The word “Kapok” means the fluffy cotton-like stuff that’s inside dolls. As the player is “playing with dolls,” I figured that it would fit quite well as the name of the currency. “Zygnoka” comes from nuclear power. It’s sort of playing on the words “sick nuke”, with a Z added so it sounds sci-fi.

Mind Scanners, of course, is not just about psychotherapy. It has this Orwellian Thought Police vibe. Does the game make a political statement? It sure supplies a lot of mottos. For example, “Don’t break the people! Break the structure!”

It is the political statement of the opposition known as Moonrise. Their actions and political statements are reactions to the stuff that goes on inside The Structure. We try to make the game speak for itself, so the players can make up their own interpretations.

Fair enough. For such a minimalist title, Mind Scanners offers quite a lot of content. How many characters are in the game? How many endings does it have?

There are over 50 patients in the game, each with their own diagnosis. Each patient has a set of reactions, appearing as events, that will trigger according to the player’s actions. The patient will react differently if they are declared “sane,” “insane,” gets stressed, loses personality or is treated successfully. Along with other factors, these actions will then determine the storypath and the ending. There are 9 endings in total.

I also quite like the tension between the story and gameplay. Minigames and money-time economy are challenging enough, but if you decide not to treat a patient, which can be the “moral” thing to do, you have to sabotage your own stats. So basically if you go for a more “ethical” scenario, you actually make the game more aggressive to the player.

From day one we wanted the moral path to be more difficult. There are a lot of games where choosing a dark path or a light path makes no difference in difficulty. We think it’s more interesting if the player struggles to become a hero. We want the players to sacrifice themselves to save their patients. If they endure, they will be rewarded for doing so.

And Mind Scanners doesn’t offer a lot of guidance either. I think I’ve seen reviews on Steam from people who were frustrated by the game’s difficulty level.

Difficulty is something we are still discussing. Mainly the lack of information given to the player, which was designed intentionally. We wanted the player to discover the function of the treatment devices themselves. This is primarily because we like this type of game design ourselves. But we also wanted to make a point that the inventions in the story are rushed in design and not tested properly before use.

Anyway, we have listened to our players, and will do what we can to make this part of the game more clear, without too much hand-holding.

A lot of people are comparing Mind Scanners to Papers, Please. Would you say it’s helping your game or hurting it?

Papers, Please sort of invented the genre, so a comparison is almost obligatory, but I don’t see this as bad. I don’t look down upon all the “Doom clones” that came out in the nineties. They all built on something that came before them and turned it into something new. Mind Scanners is definitely influenced by Lucas Pope’s masterpiece, but the game might as well be nicknamed Blade Runner The Game or The Verhoeven Simulator.

The game came out five days ago. What’s happening to you right now?

I’m sort of recovering from the intense production and roller-coaster launch, but mostly I’m just working on Mind Scanners. Haha. You never stop working on a game. Luckily we get a chance to fix the things our players are asking for, and add small things here and there that we did not have time for in the first round. But I am also eager to get started on my next game, as well as create the next chapter of my point-and-click spin-off series Tales From The Outer Zone.

You never stop working on a game… That sounds appropriately bleak! Well, good luck with Tales From The Outer Zone. And here’s to the normality and the mind of all the game devs out there!

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on May 28, 2021

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like