Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra speaks with Overlord's Rhianna Pratchett, Sam and Max's Chuck Jordan, and Leisure Suit Larry's Al Lowe about what needs to be done -- and what isn't being done -- to make games funnier.

A wise man once said, "Dying is easy; comedy is hard." This vital life lesson can certainly be applied to the medium of video games; in recent years, we've seen quite a few titles miss the mark completely when it comes to making us laugh.

This widespread comedic failure may be the reason why explicitly funny games are so disproportionately unpopular when compared to humor in other forms of entertainment. After all, Hollywood has its multimillion dollar comedy blockbusters (usually starring Will Farrell), while games with the same goals are usually met with an abundance of skepticism and retail apathy.

For every game that gets it right, there's a handful of pretenders that smear a layer of tacky, watered-down humor over tired game mechanics in the hopes that these two bad things will go great together -- like some Bizzaro World version of a Reese's Peanut Butter Cup.

In a desperate search for those responsible, who do we blame -- developers for not getting it right, the audience for not caring, or the medium itself for being unsuited to humor?

Luckily, we do have a few exemplars on both sides of the comedic spectrum to help us measure the success of humor in gaming. Take Psychonauts, for example; Double Fine's last-gen pet project set a new benchmark for funny games, and with good reason.

Instead of existing as a meaningless gimmick, the humor in Psychonauts feels completely organic, being a thorough comedic (and psychological) exploration of several uniquely hilarious personalities. Protagonist Raz doesn't mindlessly spout Gex-caliber one-liners as he travels through weird worlds; Tim Schafer and company expertly crafted Psychonauts' humor to be a holistic part of a fully-realized universe.

The jokes in something like D3's Eat Lead: The Return of Matt Hazard, on the other hand, didn't benefit from this same creative insight. It's hard to pin down the definitive unfunny game, but Hazard delivers just about every overused gaming joke under the sun. It's a generic, mediocre action game -- and the humor is intended to save it, repeatedly quipping on the subject of why it sucks. Hazard cracks wise with toothless, inoffensive jokes about tutorials and spawn points, subjects that became old hat for web comics nearly a decade ago.

Even in so-called "controversial" hits, humor exists in a certain "safe zone," disappointing those used to much more subversive and intelligent humor; the thought of a video game with the content of MTV2's subversive and strange Wonder Showzen would be unthinkable -- and even network-backed offensiveness like Family Guy had to make serious comedy concessions for its video game debut. Forget photorealism and perfected motion controls; if there's anything we need to aspire to in video games, it's simply being funnier.

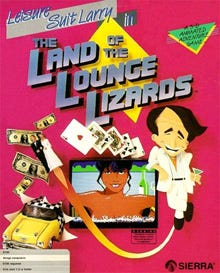

Al Lowe is no stranger to humor in video games; throughout the 1980s and '90s, he helmed Sierra's Leisure Suit Larry series, a franchise famous for its raunchy humor. His career in the video game industry took place in an era where it seemed like a great many popular games were funny -- at least on the PC side of things, with titles like Space Quest, Lowe's own Larry, and the multitude of LucasArts adventures, like Maniac Mansion.

For Lowe, this period was especially fertile: "I thought we had a handle on [humor] at some point. Back in the late '80s and early '90s with the Space Quest games and Larry and Monkey Island and some of those games... they were quite funny. I thought we were holding our own. But when the adventure game format passed away, and other formats became more popular, humor seemed to be left by the wayside."

For Lowe, this period was especially fertile: "I thought we had a handle on [humor] at some point. Back in the late '80s and early '90s with the Space Quest games and Larry and Monkey Island and some of those games... they were quite funny. I thought we were holding our own. But when the adventure game format passed away, and other formats became more popular, humor seemed to be left by the wayside."

Lowe certainly isn't shy about his stance on the current state of humor in games. When asked if he could name any recent notably funny titles he's played, Lowe replied, "No. And I don't mean 'no comment.' I mean no." Of course, you can't blame him for being so negative; after working at one of the most notable PC developers in the history of gaming, seeing the Larry series prostituted for the frat boy set has to dim your view.

But Lowe's stance is about more than seeing his personal creation disfigured by boardroom comedy; for him, the difference between today's funny games and those of the PC adventure boom rests entirely on just how much is at stake with a modern video game release; the development of the first Leisure Suit Larry took two men -- one of them only working part-time -- a total of four months to complete.

But having such a small team allowed Lowe to achieve a unique personal perspective with humor that he believes is essential for comedic success. "When committees work on things they tend to get watered down and unfocused -- particularly with humor," says Lowe. "Somebody, somewhere has to have the authority to say, 'This sucks. This has gotta go.' Humor is editing. When you don't edit, when you just put up anything that anybody on the team thinks is funny, then you get games like the games we've seen lately."

Lowe does have hope for the future, though; he sees small-budget indie games carrying the torch that he and his contemporaries held years ago. "Funny doesn't have to be expensive, and funny doesn't have to be huge. If you do a comedy, people don't expect it to last for hundreds of hours," says Lowe.

The past few years have given us some great examples of games that do just this; Tales of Game's Studios' Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden exists as quite possibly the harshest burn on the entire JRPG genre. And yet it presents itself completely sincerely, not making a point to identify the horrid tropes (neologisms, pretention, and excessive brooding) it's lampooning.

Of course, a game with such a dry, subversive approach to a topic of limited interest is only financially possible today with an old-school Sierra-sized team. "When you're talking about millions of dollars," says Lowe, "It's really tough to say, 'Sure, go ahead. Do whatever you want to. Whatever you think is funny.' [Money] makes a big difference."

Like Lowe, Telltale Games' Chuck Jordan also has an impressive amount of experience in the field of funny adventure games, though Jordan's work is limited to the later days of the genre and its recent episodic renaissance.

As the lead writer on Sam and Max: Season Two, Jordan can speak to the difficulties of making games funny. He identifies the sheer amount of writing for a single episode of the game (which lasts three to five hours), as well as the lack of a defined act structure for the medium as two major hurdles for comedy in video games, but the challenges of pacing -- a very important aspect of humor -- also prove difficult to overcome.

On the subject, Jordan states, "There's been a lot of discussion recently about how to apply traditional narratives to an interactive medium. With comedy, you can take all of those concerns and multiply them by 10."

In a more passive form of entertainment, like a novel or a movie, the artist has complete control over every element of the humor; with games, interactivity poses new problems for the comedy writer.

"[The player] can hear your punch line before the set-up. He can skip the set-up of a joke altogether," Jordan says. "He can hear 10 jokes over the course of a minute, or he can go off and wander around between each one. And the entire time, he's not just passively waiting to hear the next joke; he's actively looking for the solution to some problem."

Problems can also arise when players interpret irrelevant gags as puzzle-solving hints; this was especially an issue on Sam and Max, a series known best for its non-sequitur humor.

According to Jordan, one of the biggest obstacles with designing Sam and Max was entertaining players without misleading them: "It's in Sam and Max's character to suggest the most ridiculous and/or violent solution to a problem, so we'll have cases where Max says he needs an iron maiden or a sample of the ebola virus. And in every playtest, there's at least one player who gets frustrated trying to find an iron maiden or a sample of the ebola virus. It's perfectly natural for the player -- he's looking for answers, after all -- and the real solutions are sometimes just as weird as the throwaway gags."

Sam and Max: Season One

Despite these issues, Telltale has definitely made some progress in mastering the art of humor in gaming; those skeptical over early efforts like the now-abandoned Bone adaptation were quickly won over by 2006's Sam and Max: Season One, and this year's unexpected Telltale takeover of the Monkey Island series.

But even with such an established comedic history under his belt, Jordan still feels that humor in games can be improved, mostly in the area of dialogue writing. "There's still this idea of 'good enough for video games' that we all just kind of accept, and it usually comes across sounding stilted and overly expository, instead of sounding like the way real people talk," he says.

For Jordan, comedy shouldn't have to be entirely resigned to dialogue and writing; the designer cites Valve's Team Fortress 2 as a comedy game that was never marketed as such. Like Schafer's Psychonauts, Valve invested a great deal of care into the creation of Team Fortress 2's world; but unlike the former, TF2's humor is rarely sold through dialogue alone.

While the characters do have spout out some short utterances for the sake of teamwork (or trash-talking), most of the non-interactive absorption of comedy -- watching funny dialogue and animation -- is limited to out-of-game content, like the comedy shorts featuring the iconic TF2 characters. The humor inherent in playing Team Fortress 2 comes from inhabiting one of these uniquely funny characters, and, well, blowing the rest of them up.

And Jordan's comments about the unified comedic vision of Team Fortress 2 mesh with Lowe's opinion on how such a mentality is necessary for humor to work in gaming. "It feels like everyone on the team is in on the joke, from the character designers to the level designers to the voice actors to the marketing team," says Jordan.

Team Fortress 2 isn't the only game to take humor out of the adventure gaming genre "safe" zone and make it work elsewhere; Codemasters' Overlord series -- a twisted take on Nintendo's adorable Pikmin -- has become one of the secretly funny franchises not sold primarily on its comedic potential.

Responsible for this feat is Rhianna Pratchett, who wrote for the Overlord games, as well as more straight-laced efforts like EA/DICE's Mirror's Edge. As the daughter of British comedy legend Terry Pratchett -- known mostly for his Discworld series of novels -- it's clear that she comes from good comedy stock.

She also has a lot of insight into how to make games funny. According to Pratchett, subverting the typical fantasy adventure by putting the player into the shoes of the "bad guy" makes the humor in the Overlord series successful; and this sense of mischievousness permeates nearly every level of the game.

"I think the reason it worked is that we gave the humor a multi-layered approach. So the gameplay itself, in which you control a horde of sycophantic, gremlin-like minions that loot and pillage at your command, was inherently fun."

"This was then translated through the rest of the game -- from the environments and characters you meet, through to the animation, script and voice work. We approached it wholeheartedly and I think players appreciate that," says Pratchett.

Like Lowe and Jordan, she believes that comedy in games can't just be an afterthought, unsurprisingly citing Psychonauts as an example of humor coming out of a game's fully-realized vision.

"Good humor needs to be built in," Pratchett says. "It should be the chocolate chips in the gooey cookie of gaming, rather than chocolate sprinkles on top." And this seems to be the prevailing sentiment amongst the writers and designers interviewed for this feature. But if these talented folks understand how to make games funny, why do so many others seem to just not get it?

Overlord

It's clear that the environment in which video games are produced can often drain the humor out of what could be a funny game; after all, in our dog-eat-dog economy, the almighty dollar often takes precedence over creative license. Still, in listening to the words of Lowe, Jordan, and Pratchett, we can at least identify three essential lessons for success with humor in video games.

1. Humor isn't an afterthought. Making a funny game involves more than slapping some humorous dialogue or text on some game play that isn't funny in and of itself. A funny video game should be designed from the ground up to be funny.

2. Great humor comes from a unified vision. Some of the funniest titles ever were created by teams who put a lot of thought into developing characters and a world for their games. There's a reason why Psychonauts gets namedropped so much.

3. We need to expand our humor horizons. People are enjoying increasingly complex forms of comedy in other forms of entertainment, making video games look like Vaudeville in comparison. Experimental humor in television, movies, and print is leaving video games in the dust.

The best part about these lessons is that they don't require any hefty technological advancements or expensive research -- just some common sense about good comedy. And that's an investment anyone can afford to make.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like