Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Like Darkest Dungeon, Torchbearer is a love-letter to the 1st Edition D&D dungeon crawl. But each goes a step further in emphasizing scarcity, and the grittier aspects of dungeon-delving.

Red Hook Studios’ moody and infuriating Darkest Dungeon has met with a lot of critical praise (including from yours truly). Its atmosphere, its bracing strategic challenges, its willingness to explore the darker side of dungeon-crawling, all earned plaudits for Red Hook.

I particularly liked the fact that, unlike most games that flaunt their difficulty, there was a sobriety and maturity to Darkest Dungeon. It didn’t need to beat its chest about how challenging it was; the developers had the confidence to let the game speak for itself. And oh the things this game said.

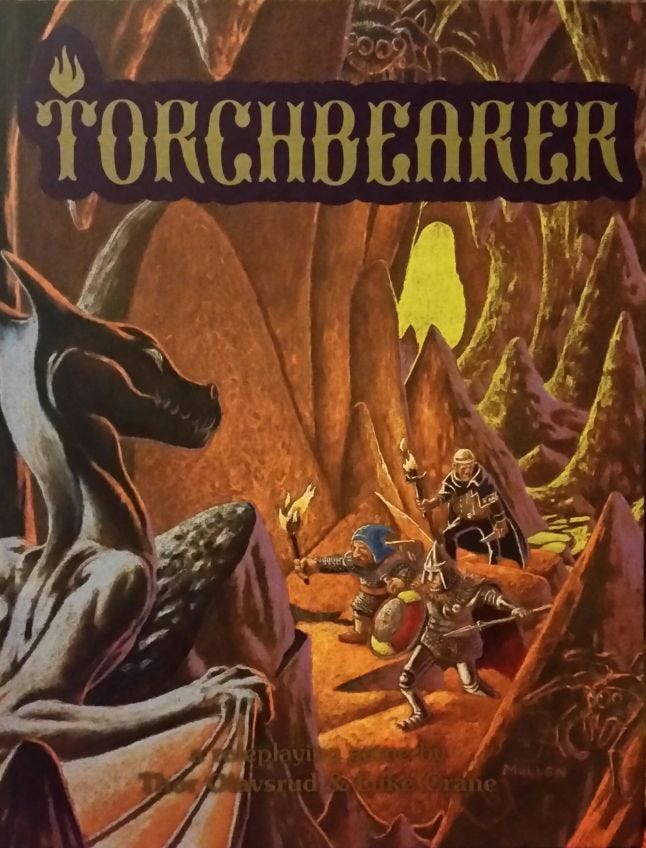

What I did not know is that Darkest Dungeon was inspired, in part, by a tabletop RPG: Burning Wheel’s Torchbearer, which was sporting several freshly printed adventures and new Nordic setting at GenCon this year. If you liked Darkest Dungeon, and you’ve had a hankering to recreate its experience at your gaming table, then I’d very strongly recommend taking a look at Thor Olavsrud and Luke Crane’s Torchbearer.

Like Darkest Dungeon, Torchbearer is a love-letter to the 1st Edition D&D dungeon crawl, fully surfacing that aspect of RPG gameplay. But each goes a step further in emphasizing scarcity, and the grittier aspects of dungeon-delving. All resources, including light itself, are limited and both games emphasize the management of these vanishingly limited resources while fighting for your very lives over scraps of loot. “Safe Havens and Other Poor Assumptions” is a chapter title.

It’s not for the faint of heart, but mercifully neither game gives into macho preening about that fact.

Torchbearer is a game that evokes old D&D, it seems, right down to its layout’s design and the stark black and white artwork. There’s a nostalgia factor at work, certainly, and while we’re currently awash in a media deluge of tedious sops to childhood pop culture, this one works.

I’ve recently written about RPGs that emphasize the storytelling and worldbuilding aspects of roleplaying. Well, Torchbearer does the opposite, refining the dungeon-crawl and emphasizing the rigors of adventures down there in the dark. A combat-laden adventure, far from civilization, is the primary setting of Torchbearer and its reason for existing. Everything bends in service to this.

"Despite Torchbearer's emphasis on dungeon-based combat, there’s scope for story-based RP, as well as side-quests that can stem from the Town phase. There’s scope for things like cartography, language skills, and scholarship."

This back-to-basics approach is what makes the game’s conceit of “You All Meet At an Inn…” something more than a grating cliche. For something meant to rhyme with Gary Gygax’s early works, this is actually an acceptable trope to use.

Players of Darkest Dungeon will find Torchbearer’s structure familiar. There’s a town with distinct buildings that perform specific functions, all of which may help (or more likely hinder) your character; there’s a camp phase whilst your adventuring, where you have highly structured rules that make recuperation feel like a mighty accomplishment indeed; over the course of adventuring you earn Conditions that affect your character’s disposition in a variety of ways. But unlike DD, Torchbearer is a bit more open. Despite the emphasis on dungeon-based combat, there’s scope for story-based RP, as well as side-quests that can stem from the Town phase. There’s scope for things like cartography, language skills, and scholarship.

What remains constant, however, is that rest is elusive and you’re bound to go from the frying pan into the fryer. Forgiveness is in short supply. The eponymous torchbearer is, after all, an important figure; they have to hold the damn thing instead of a shield or a two-handed weapon. You can’t fudge that either. Dropping the torch incurs a sharp penalty to the light available to your group, which in turn applies a penalty to combat. What’s more, the dropped torch can be snuffed out at the GM’s discretion for any reason. A lantern won’t fare much better: “the GM may decide the lantern is kicked over in the fray and doused at any time--regardless or in addition to any other results.”

That’s what sets this game apart: attention to those seemingly minor details that other games necessarily take for granted or otherwise elide. The trick here is that such choices aren’t arbitrary; the “realism” that gets emphasized is comprised of those aspects of play that are necessary for creating an experience that’s both challenging and sensible, where a player can easily intuit what they need to be paying attention to. Broadly, this is a survival game, where one has to monitor food and drink carefully, and even a rat bite can ruin your day.

"Burning Wheel’s systems are about mood, using game mechanics to suggest an environment that would naturally flow from them."

Burning Wheel’s systems are about mood, using game mechanics to suggest an environment that would naturally flow from them. Torchbearer is not a setting, strictly speaking. Late in the book, you’re given generic places--Elfland (which makes me giggle), the Dwarven Halls, the Bustling Metropolis--that you’re told to give your own proper names to. There is no world here. But Torchbearer is powerfully suggestive all the same; its rules are painted in dark colors indeed, and the demands of the rulebook evoke specific kinds of player-characters. You’re not bedecked in glittering armor, the object of public affection; you’re not a great hero, you’re just a schmuck trying to get by. “There are no jobs, no inheritance, no other opportunities for [you] deadbeat adventurers. This life is your only hope to prosper in the world,” reads the introduction, which also describes the otherwise generic fantasy world as “a grim land.”

The specifics are up to you, but Olavsrud and Crane clearly want you to play in a grimdark world where hope is yet another scarce commodity you have to greedily hoard. Sometimes they come right out and say it, but the rules of the game do a fine job of expressing this. It’s worth studying if you’re interested in designing a game where the mechanics do the talking for your setting.

Indeed, a Burning Wheel blog post put it this way: “Traditionally, we eschew setting and focus on evoking atmosphere through the rules.” But this was from a post about a recent exception to that rule: Middarmark.

Middarmark is a proper setting, complete with a gazetteer by Thor Olavsrud, and it was actually what prompted me to take a look at Torchbearer proper, which I might otherwise have passed over. Middarmark is a thing of beauty, both in terms of its suitably epic looking artwork and the strength of Olavsrud’s worldbuilding, which both draw heavily from Norse mythology and Scandinavian history. I hesitate to use the word “Viking” here as that may undersell and efface the complex anthropological project Olavsrud engaged in, but it provides a useful hint to its overall atmosphere.

"Middarmark is a thing of beauty, both in terms of its suitably epic looking artwork and the strength of Olavsrud’s worldbuilding, which both draw heavily from Norse mythology and Scandinavian history."

There aren’t any longboats (or at least, no specific rules for them). Instead, the focus lies on life in the windswept Middarmark and the dangerous adventures it demands. The grimdark mood is muted here, as if dispelled by light reflecting off the snow. You’re still dealing with the Torchbearer ruleset, of course; scarcity and rage at the dying of the light. But Olavsrud’s setting lacks the empty desolation that was so powerfully projected by the core rulebook. It’s hard to feel completely ground down when you’ve got your Fylgja (a Norse spirit animal) by your side.

Of course, the character creation chapter is entitled “Destined to Die,” so your hope-mileage may vary. Even so, this is a land where heroic Wagnerian horns echo off of its landscape; I’d rather roleplay my destined-death here than in the bleak hellscape demanded by Torchbearer. That’s a matter of taste, however. Both the base game and Olavsrud’s campaign setting have much to recommend them, and have a lot to offer to the player who yearns for a challenge free from the immature M-rated preening that infests so much of gaming culture these days. Middarmark just stands out as an efficient yet accomplished setting, packing a lot of lore into its hundred-even pages, including a rich cast of queens, jarls, huskarls, skalds (a playable class, by the by), and shaman. The pan-Scandinavian influences are used well to create a culturally rich brew--one that goes beyond anachronistically horned helmets to give us a truly heroic setting.

Olavsrud managed to create a bright torch in the darkness of his own ruleset.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

You May Also Like