Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A zine by the creator of tabletop RPG Monsterhearts 2 details the story of the series’ origins and her thinking behind updating the Powered-by-the-Apocalypse game.

So, full disclosure up front: I backed the Kickstarter for Monsterhearts 2--a popular little tabletop RPG that sees you play as a supernatural high schooler managing drama, romance, and the underworld. As a lover of games that deal maturely with relationships, I was instantly drawn to Monsterhearts’ original incarnation, so backing the updated version was a no-brainer.

But I’m writing this because the level I backed at netted me this lovely little tidbit: a zine from the game’s creator, Avery Alder, detailing both the story of Monsterhearts’ origins and her thinking behind updating the Powered-by-the-Apocalypse game.

It’s a rather unique way of reflecting on the process of game design, marrying that punkish world of indie zines to the domain of professional games publishing. But a zine is about so much more than aesthetics; it’s a personal artform, something that took “confessional” writing to both a high and low art long before it became the medium of choice for so many young writers online. Zines are handcrafted affairs, their layouts done by hand in a collage style that assembles text and images into something ready to be raptured into a Xerox machine and stapled together with love.

The very nature of the craft resembles the bespoke care put into the making of an indie game, whether tabletop or digital.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Alder’s reflections begin in handwritten form, a beautiful touch that obtains throughout the text--though some bits were printed before being pasted in, which, in any event, creates a nice offset. She opens by listing the “four beginnings” of Monsterhearts, each a different origin story for the game marching forward in time and perspective.

"I slowly realized that I’ve been designing it because it contains lessons I need to be learning."

As she notes later, the game had an emergent theme of queerness. It used its supernatural theme to create an atmosphere of “internalized shame about difference,” where classic supernal tropes like vampirism became metaphors for queerness--in much the same way, I hasten to add, Dragon Age’s mages have been read as a complex metaphor for LGBT life.

“I slowly realized,” Alder writes, “that I’ve been designing it because it contains lessons I need to be learning.” That personal angle to game development is something that’s often missing from postmortems of a more heroic cast, where the developer is positioned as a diviner of some timeless truth pulled from the ether. This is, of course, sometimes quite true and fun, but it’s hardly the only wellspring of inspiration, nor the only mother of invention in this field.

The creation of the original Monsterhearts was, for Alder, a prelude to coming out and accepting herself, and a way of thematically exploring territory that might’ve been too intimidating otherwise. As she says of her own players, “Sometimes people are excited to play with metaphors because it gets them closer to the truth, not further away.”

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

That, I think, is one of the most important lessons for game design today, particularly for developers looking to make an “artsy” game of some description. Such games are vulnerable to becoming too fascinated by their own cleverness, getting lost somewhere up a digital cloaca of floating signifiers (much as I may personally like a few such games). But as Alder notes towards the end of her zine “there are ways to make deconstructivist/postmodernist/anarchic art without willfully making it esoteric, unreachable, and inaccessible.” There is a happy middle ground to be found which lies in that recognition of the power of metaphor, something that gets to the very heart of what it means to game.

"The second edition of Monsterhearts contains a lot more focus on queerness and queer shame because the game has slowly revealed to me how that was always already central."

Every videogame is, after all, at a level of abstraction from the reality its images refer to. It is, to some degree, metaphorical. Yet the magic of metaphor lies in its ability to bring us closer to reality while distancing us from it; once again, we return to an essential aspect of gaming. Being at once outside and within the “real world,” escaping from it but also glorying in it. Alder understands this quite clearly, not only from the perspective of the player, but of the dev whose work gets away from her in a beautiful way.

In her handwritten zine notes, for instance, she says “the second edition of Monsterhearts contains a lot more focus on queerness and queer shame because the game has slowly revealed to me how that was always already central.” To develop is a game is, often as not, to set events in motion that you eventually lose control over. Emergent themes will blossom among your players and reveal to you hidden depths that were hitherto invisible to you as a dev.

Of course, sometimes what emerges are seemingly insoluble flaws. In the case of Monsterhearts, a relic of Powered by the Apocalypse game design bedeviled Alder. In Apocalypse World and its related “Powered By” clones, when you roll up a character, your fellow players and the GM may highlight certain stats of yours which give you an ongoing bonus to any rolls you take with that stat. But, as Alder noticed, this simply led to a gaming of the system that undermined the intentions behind the mechanic (i.e. incentivizing a player to try rolls on stats they weren’t good at, in a bid to give RP depth to their character). “People would pout if their weak stats got highlighted. And if their good stats got highlighted, they would lean on those moves almost exclusively throughout play,” Alder wrote.

"Sometimes good game design is like good architecture: the genius lies not in what you add, but in what you can take away."

The solution to this was to make Monsterhearts 2 a game that truly rewarded a diversity of stat rolls. Using your weak stats “creates more opportunities for painful growth (and, ultimately, advancement)... making weak moves gets you tokens, which help you kick more ass later.”

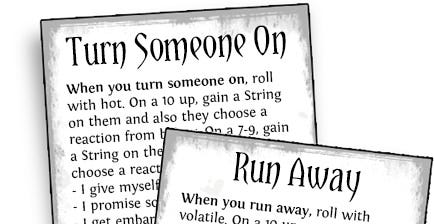

Sometimes good game design is like good architecture: the genius lies not in what you add, but in what you can take away. Alder’s approach to Monsterhearts 2 was very much minimalist in that way, wherein she emphasized certain existing themes instead of pure novelty. She was after a “tight experience at the game table,” flowing from a streamlined game. In the process, iconic moves like “Pulling Strings”--where you manipulate someone into doing what you want-- were pared down into something simple and elegant that worked for both other players and NPCs.

The last section of the zine lists all of Alder’s answers to the “1 like = 1 insight from designing games” Twitter meme and contains more than a few gems. It seems fitting to close with one:

“When critiquing or developing a game, use the toddler technique: ask “why? But why? But why?” until you arrive at something profound.”

I might prefer to call this the “sociologist’s technique” but then there’s always something to be said for wisdom from the mouth of babes. The instinct to question the very foundations of the world around them is surely the most pearlescent bit of that infantile wisdom, and it's something that would serve every game dev particularly well.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

You May Also Like