Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra contributor Katherine Cross examines how Robot House's emotional robot vacuum adventure game Rumu gets at the true nature of love.

"You don’t want to know what not-love feels like."

- SABRINA

When Roombas dream, do they dream of electric feels?

Robot House’s Rumu seeks to enthusiastically answer that question by charging headlong into highly charged emotional territory. You play the titular RUMU, a Roomba-style cleaning robot operating under the watchful eye of SABRINA, the household AI; you can think of her as a truly omnipresent Alexa, whose voice is pegged by various illuminated panels and baseboards throughout the house.

You feel nothing but love. You love mess. You love to clean mess. You love SABRINA. You love everything. Happily, you live with your inventors, Cecily and David Boothe. You love them, too. Less happily, they always seem to be away when you’re awoken to perform some household cleaning.

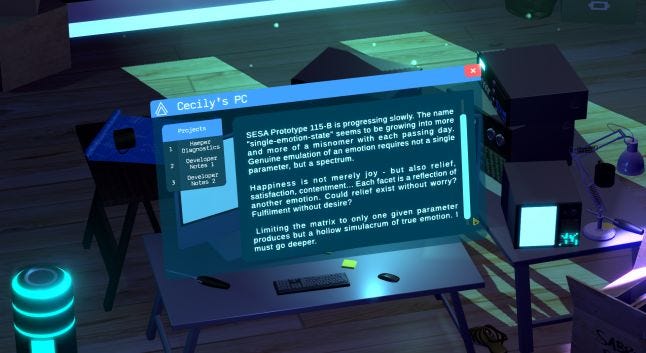

Like so many exploration and adventure games of its ilk, Rumu is about solving an emergent mystery--this one happens to involve emergent behavior. Where are Cecily and David? And why does SABRINA’s emotional facade seem to crack in strange ways? ...And why does the household management AI have an emotional facade in the first place?

Before getting there, we need to talk about what kind of game this is, and the emerging tradition it stands in.

***

Books and film have thrived on mining the quotidian for profundity. Indeed, that forms the foundation of what we think of as “literature” and highbrow film: having a firm tether to the limitations of reality.

Though some might argue the point with me until the Second Coming, I think it’s always been a strength of video games that they went in the opposite direction, drilling deep into the realms of the fantastical, conjuring genre fiction that was pulpier than pulp. I think, however, that because this has come to so thoroughly define video games as a concept, anything that deviates from such explosive fantasy is seen as somehow un-game-like. It’s why titles like Dear Esther or Sunset attract so much controversy, even above their mechanics (or what some deem their lack thereof); it’s that their subject matter is seen as unworthy of a videogame. Why delve into all this domestic, interpersonal drama when you have the tools to create something phantasmagorical? That sense forms at least part of the “why didn’t you just make a movie?” critique.

There are many ways to respond to such criticisms, of course. Video gaming makes the player complicit in a way that other mediums struggle with, and all the aforementioned games depend heavily on that. You can’t get that effect, generally, without the minimalist approach of such games. Tacoma, The Stanley Parable, and The Town of Light each, in their ways, have to redefine interaction to show how a feathery touch can still leave one intimately involved in a game. Event[0]’s heart and soul lies in social interaction, where dialogue with its AI drives the whole story.

But there are other ways too--compromises between classical gaming elements and emotional focus. Rumu has revealed itself to be a perfect example of this.

It has some rather cunning puzzles, and even a few moments that seem to wink at adventure games--nothing too mind-bending, but exploration is richly rewarded. This is a tactile world where there is joy in, say, 3D printing a teacup over and over again because it falls on the floor and breaks each time. Or fiddling with the toaster to adjust the launch trajectory of your burnt toast. The game’s climax has an incredible use of interactivity, however, that echoes the subtleties of Town of Light. It asks you to perform a task that is at once simple but moving, where your complicity in the act puts you in the moment. Suffice it to say, the basic mechanic of cleaning up a mess gains unexpected depth.

In that long arc-- from a tutorial that you have to decide to walk (roll) away from, to a climactic moment that is at once dream-like and visceral-- you have a superb theatre of memory that makes for one of the year’s most moving indie experiences.

That tutorial, by the way, betrays the genuine cunning of a minimalist mechanic. How do you take basic movement and make it creative? You have to ask the player to step back and think for a second, but subtly. Encourage them to roam, but let them figure it out. Eventually, you might just roll over the answer. The tutorial sees you in a training area overseen by SABRINA. She guides you through the cleaning mechanic. A splotchy mess appears and you have to drive over it until its clean. Then another appears. Then another. And another. Until you realize your task tracker says “4/99 messes cleaned,” a subtle cue to the player that perhaps something’s not entirely right here. So you move and explore.

And then, “I love door.” Little moments like that indicate how subtle interaction can be achieved in games where one still wants to centre emotional exploration.

Cleaning messes is the most elemental action in the game. It’s also a not so subtle metaphor for RUMU’s role in the larger drama.

***

Of course, the great thing about making “loneliness” your theme is that you save a ton on character modeling and animation. But one must, of course, follow through. Robot House’s game is beautiful, and a reminder that elegant writing can be worth far more than lavish character models in giving you a feel for a person. You have words and disembodied voices, the detritus of a life left behind, and it adds up to people you can feel something about. That includes SABRINA, of course.

Perhaps one of the game’s most powerful moments comes when you see what a robot emotionally abusing another robot looks like. This is, after all, a game about AI achieving sapience. The very old theme of “how does a robot handle complex emotions?” is present, of course, but Rumu wisely sticks to exploring two specific emotions: loneliness and grief. Strangely, “love” doesn’t quite make it as a theme. If there’s one thing about the game that doesn’t quite work, it’s the way the climax is resolved by attempting to define love--in so doing, we strayed into rather pat, Hallmark card territory. But it’s more than made up for by the otherwise tight focus on those other two emotions and the novel way they’re handled.

In this way, Rumu successfully splits the difference between genre fiction flash and the emotional explorations of, say, Gone Home. It combines the deft touch of Town of Light with traditional RPG puzzles. It even has some notable nods to arcade games. In short: it’s a game for partisans on all sides of the videogame debates to sit down for a Christmastime truce with.

“Love is the Turing Test.” This quote from author Catherynne Valente appears late in the game, suggestively enough. But Rumu makes a case for Cecily Boothe’s hard-won perspective on the matter: every emotion is a facet of every other. And if this game has anything to say about love, it’s that its darkest facets are the ones that make it the most meaningful.

You May Also Like