Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What the developers of Way of the Passive Fist learned from collaborating with Clint "Halfcoordinated" Lexa, a speedrunner who plays many games one-handed, helped to ensure maximum accessibility.

“As a creator, I of course want everyone to experience what I create. For any game that I develop I want as many people to play it as possible. Some will enjoy it, some less so, but it is important that as many as possible be able to.”

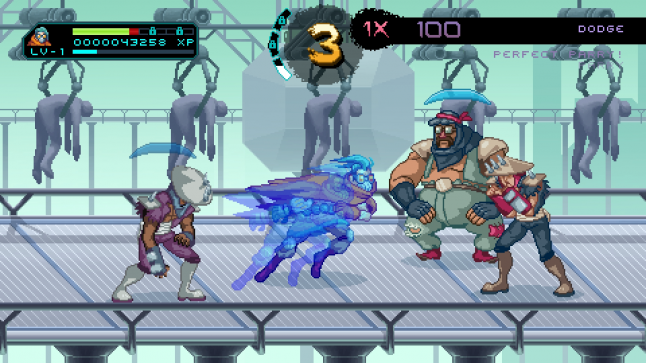

Way of the Passive Fist is an arcade brawler that takes players to a colorful world of misfits and danger, but one that turns the genre on its head through a defensive style that emphasizes learning the enemy and playing smart, rather than brute force takedowns.

Not only is Jason Canam, who directed development with the team at Household Games, looking at the genre in new ways, but he’s also looking at games in new ways, working on accessibility to ensure that as many players can enjoy his game as possible.

Through assistance from Clint "Halfcoordinated" Lexa, a talented speedrunner who plays many games one-handed due to a condition that limits the use of his right hand, Canam looked to get advice on how to open the game up to more players of varying abilities and play styles, making sure as many people could play as possible. Canam wanted to remove those barriers that standard controllers and genre conventions created for many players, looking to create fun for all.

“I think it’s my job as a developer to remove as many barriers as I can, from the software side of things and that’s what our team has been working towards while creating our studio’s debut title Way of the Passive Fist,” says Canam.

Way of the Passive Fist will be playable at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto later this month,

and at the Indie Megabooth at PAX Prime early next month.

Canam has been in game development for years, having worked on Guacamelee, Severed, and many other titles. Despite this experience, that didn’t mean that there was nothing more for him to learn about game creation, as he came to see during a speech from Lexa at the end of one of his speedruns.

“I have been a fan of Halfcoordinated for a few years," says Canam. "I follow his Twitch channel and love his Vanquish speedruns! So, going into Summer Games Done Quick (SGDQ) 2016, I was looking forward to his run. He was fantastic, and at the conclusion of his speedrun of Momodora, he gave a passionate and energizing speech about how important it is to push beyond your limits. It truly was an epiphany moment for me.”

This is one of my favorite moment of #SGDQ2016

— к ε v ғ ι η ~ (@KGPrestige) July 6, 2016

What a moving speech by @halfcoordinated pic.twitter.com/dJ36N9Khr8

Canam had seen Lexa playing games in his own unique way while using a controller that was clearly geared toward players who play with both hands. This made Canam realize something about the games he built, and one he intended to create.

"We knew we wanted to create a game that did as much as possible for accessibility, but we needed guidance on what specifically we could do to accomplish that."

As a developer, Canam felt it was his duty to make sure as many people could play his games as possible. It seemed almost silly to work within the conventions he knew would limit the game from a potential audience, or to just ignore the fact that reams of potential players might not be able to play his game just because he did things as they had always been done before.

“He really is an inspiring individual, which is why I instantly knew I wanted to collaborate with him," says Canam. "I reached out to him and he very politely replied that he was interested, and that was the beginning of our Way of the Passive Fist collaboration story.”

Canam might have an idea on what to do to increase accessibility, but going to someone like Lexa, who would know first-hand what would help make things easier for players like himself, would open up all new development avenues for Way of the Passive Fist, letting it broaden its audience and tell a lot more people they were welcome to play.

“Because we began this process in the very early days of the project (the game began production in July 2016, around the same time as SGDQ)," says Canam. "We were able to approach accessibility development as a blank canvas and ask him about how best to proceed. We knew we wanted to create a game that did as much as possible for accessibility, but we needed guidance on what specifically we could do to accomplish that.”

“Since Lexa is very knowledgeable and passionate about accessibility, he was able to provide us with a clear and detailed guide that we could initially follow. And that’s the most important part of this: the fact that we started this process at the beginning of production was key,” says Canam.

“Often, accessibility is brought up very late in production and the responses are often ‘Well, it’s too late to change that now.’ or something of that nature. With Clint’s recommendations and guidance, we were able to build a foundation for our systems from the ground up with accessibility in mind.”

"Often, accessibility is brought up very late in production and the responses are often ‘Well, it’s too late to change that now.’"

Canam started off with accessibility in mind – not as an afterthought, but as something that was in place right from the design process. In this way, he would change his mode of thinking right from the start, making an important shift in the game’s creation.

“If you change your mindset from 'Accessibility means we can’t do [feature]' to 'With accessibility in mind, let’s do [feature] this way,' you will achieve exactly the same thing or create something even better,” says Canam.

This was a key distinction. Rather than build the entire game a certain way and then try to fiddle with things at the end to force them to try to adapt something existing into a more accessible model, the developer created things from the beginning with accessibility in mind. How can this feature be created to open it up to more players – how can it be reimagined to be more welcoming to more players.

This would give Canam a blank slate to work with the helpful advice he was receiving from Lexa, who was opening his eyes on all manner of features. “We had vague ideas of what we wanted to do, but didn’t have the knowledge to know how best to tackle these challenges to achieve our end goal," says Canam.

"One thing that we hadn’t considered at all was players with varying cognitive ability levels, which can include delayed reflexes or being overwhelmed by too much information. That made us stop and think about what we are asking the player to do and how much time we’re giving them to do it."

“For example, we understood colorblindness, as a concept, but Lexa provided us with guidance and worked closely - again, from the very beginning - with the art team and let them know what they could do to test their color schemes and palettes to minimize issues," he continues.

"The same thing goes for audio and control considerations. He had specific plans of action in mind, and together we mapped out how we were going to develop all of our underlying systems to accommodate these features from the get-go.”

Lexa had more advice on other aspects of games that might be limiting to certain players as well. “One thing that we hadn’t considered at all was players with varying cognitive ability levels," says Canam.

"This can include a delay in reflexes or being overwhelmed with too much information. That made us stop and think about what we are asking the player to do and how much time we’re giving them to do it.”

Lexa’s advice gave Canam many different things to consider, but rather than trying to alter an existing game to make them happen, these ideas were brought into the creative process, giving Canam exciting possibilities on how to make the game work with them. It was this invaluable advice, and Canam taking it to heart, that allowed him to work genre features, difficulty, and play styles into new shapes.

Few of which he would have known to work towards without knowing he had to ask someone who dealt with these challenges. “Lexa brought an expertise and knowledge that we didn’t have and therefore he put things into contexts we hadn’t thought of,” says Canam. “His input was vital to taking our good intentions for Way of the Passive Fist and turning them into actual achievable implementations that we could put into the game.”

In reaching out to people more knowledgeable than him in experiences with dealing with lack of accessibility options – without a look outside his own perspective in games – he would not have been able to create the project he is currently quite proud of.

"An accessibility feature can be used to enhance or improve a game for more players than just the intended audience. "

Canam has implemented Lexa’s advice in many different ways, and in doing so, not only created something more accessible to players, but also a game that takes the genre in unique directions that will help Way of the Passive Fist stand out from other brawlers while still being an homage to the genre’s history.

Through his work with Lexa, Canam has seen that working toward accessibility also benefits all players, making developers think outside convention to create new features. “People often forget that some of the most common game features were originally accessibility features, the most obvious example being subtitles,” says Canam.

"Subtitles are a necessity for the hearing impaired, but they also enhance and improve my gaming experience."

“I play every game with subtitles on, always," he continues. "Games often communicate important information to the player that must be retained (such as learning a button prompt for an action, or being told a target or objective) and for me, I can retain information more easily if I read it."

"Reading that I have to ‘Travel to Megaton’ is much more useful to me rather than just hearing an NPC say it. An accessibility feature can be used to enhance or improve a game for more players than just the intended audience. In this case, subtitles are a necessity for the hearing impaired, but they also enhance and improve my gaming experience.”

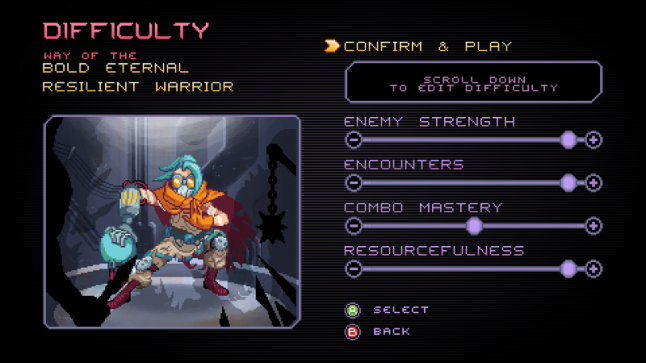

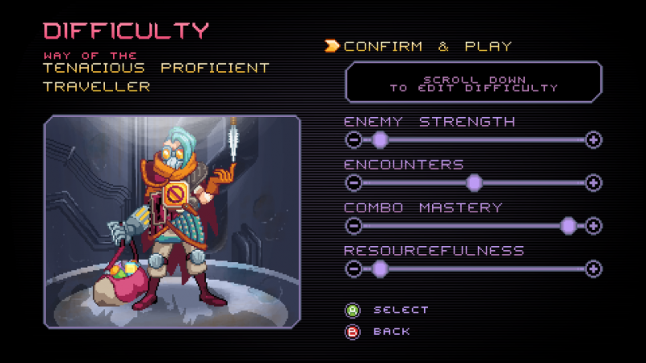

This was what shaped Way of the Passive Fist’s dynamic difficulty. Instead of static challenge modes, the game features an array of sliders that control enemy strength, encounters, combo mastery, and resourcefulness, altering the game’s various challenges to suit players of different styles and needs. Not only that, but the game would create a different name for each difficulty mode the players could concoct, taking out that implied shame some may feel from choosing a lower difficulty level.

“This applies to our customizable difficulty setting feature," says Canam. "What started out as a feature intended to help players who can become overwhelmed with overcrowded information on screen, or with varying reaction times, has evolved and become a feature that impact all players.”

"Lexa informed us that there are players who hold controls in non-standard ways so you really have to keep that in mind. It’s one thing to allow face buttons to be remappable, but if the player holds the controller vertically then you’re not providing what them with a full solution, it’s just a half-measure."

This new difficulty not only brings more players in, but offers new challenges and play options for players as well. “It’s also an excellent feature for players who wish to hone their skills in the game. If you want to practice your razor-sharp parry timings but you’d like to do so against enemies that will do less damage, then you can do that."

"If you want to practice achieving high combos by fighting a ton of enemies at once but don’t want them to do a ton of damage, that’s also a possibility. These are things that exist in most games with varying difficulty settings, but they have an all or nothing approach. You get more enemies and stronger enemies, not one or the other,” says Canam.

These new, fun options don’t just apply to difficulty, either. They’ve also allowed Canam to play games in ways he hadn’t tried before as well.

“With this full implementation, I have successfully and seamlessly played Way of the Passive Fist one-handed with my left hand and with my right hand and without the use of my hands by mapping all movement and actions to the thumbsticks directions. It’s the most freedom we can provide within the context of our game,” says Canam.

And all of this, again, is thanks to Lexa’s advice, and Canam’s desire to listen. “I knew that I wanted to have remappable controls, and Lexa was once again able to provide valuable insight. He informed us that there are players who hold controls in non-standard ways so you really have to keep that in mind. It’s one thing to allow face buttons to be remappable, but if the player holds the controller vertically then you’re not providing what them with a full solution, it’s just a half-measure,” says Canam.

“With that in mind, we made sure that we would allow as much of the controller as possible to be remappable: all directions on d-pads & thumbsticks, as well as all face buttons and shoulder buttons.”

In setting out with this mindset, Canam was in no way compromising his vision. Rather, he was broadening it and taking it in new directions, both to help more people be able to play it, and also to grow in new play directions, as a developer. In doing so, Way of the Passive Fist is paving new ground in brawlers, and giving players some new experiences that will invigorate the genre and give future developers new things to consider.

“This project has reinforced and strengthened my opinion that design and accessibility work best when both are given equal weight and dedication," says Canam. "In our case, an accessibility-focused mindset informed and improved designs with absolutely no loss to the game. There were no compromises made.”

You May Also Like