Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"I have always been interested with those moments in time where we have seen the greatest kindness in humanity combined with the most atrocious acts of hatred. How can I capture that in a game?"

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday casts players as Reza, a photojournalist during the revolution in Iran. Players are asked to guide the young man's actions during this time, from his behavior among family and friends to his relationship with the rebels to his acts when the people are under attack, letting the player immerse themselves in the normal lives of people affected by this conflict.

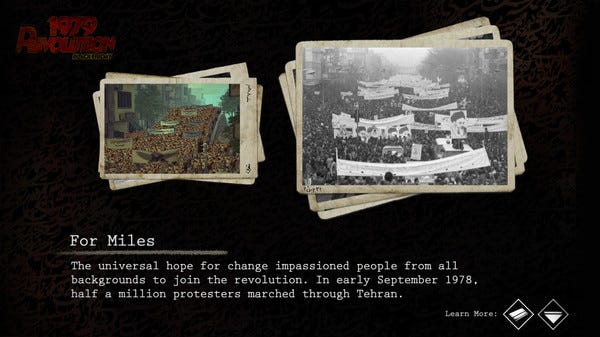

Drawing from interviews with those who'd experienced the revolution, in-depth research, and actual photographs from the time, 1979 Revolution: Black Friday captured the look and feel of the period, letting the player soak it all in while letting them make choices based on the events they witnessed. By placing them in this world informed by the realities of history, its developers sought to make players feel it, rather than just read about it.

This approach to design and capturing history earned the developers at iNK STORIES a nomination for Excellence in Narrative from the Independent Games Festival. Gamasutra spoke with Navid Khonsari, 1979 Revolution: Black Friday's director, to learn more about how the team created that living history, and how games can help people internalize history and world events through choice.

I actually started in film. I did my first feature with Billy Dee Williams right out of film school, and then moved to NY where I met the founders of Rockstar. They were looking for someone to bring cinematic elements that were essential to their vision on GTA 3, and that's how I started off at Rockstar Games - as a cinematic director.

I played a lot of games growing up, and in many ways it was instrumental in me connecting with other kids when my family first moved to Canada from Iran. I stayed at Rockstar for 6 years and got to work on everything. It was amazing. After leaving Rockstar, I went on to make documentary films while still directing games like Alan Wake and Home Front, and today I am super excited about the work I did as the cinematic director on Resident Evil 7.

I have always been interested with those moments in time where we have seen the greatest kindness in humanity combined with the most atrocious acts of hatred. So, that was the catalyst - how can I capture that in a game - because my experience has shown me that games are the most powerful way to leave an impression on a person. So, seeing that I had lived through the Iranian revolution and had seen the spectrum of joy, sadness, grief, and rage I felt I would aim to tell this story in an interactive way.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday was developed using the Unity Engine - a highly customized version of Unity that could do the things we needed it to do, create "cinematics" that were playable in game, and we then built a lot of additional plugins for Unity that helped consolidate and implement the narrative, choice-driven elements of the game.

Beyond programatic tools, we shot the entire game in Motion-capture with the actors who also voiced the characters in game - a full Iranian cast. This was something indie-games never do, and it was important for us because it infused the characters with their performers even more, and gave us a really great, complete set of animations which we used to build all the cinematics and miscellaneous crowds in the game.

The game was in the works since 2011, but the actual production cycle, from pre-production to release, was about 18 months. A lot of that pre-production went into the research process for developing the game, during which we did over 40 interviews with different types of people who had lived through the Revolution - and these interviews ended up greatly informing the narrative and characters we developed for the game. They gave a great deal of additional context and authenticity to the experience of the game, and that was really, really important for us, to have all these elements of gameplay and narrative growing out of the actual history and real events - to combine the elements of a documentary into the design of a game.

The 1979 Revolution is one of the most defining moments of the 20th century - we are dealing with the impact of that revolution today, so for me it was very relevant, and through experience in the past, we might be able to understand the present. As I mentioned, I lived through the experience personally, but also was seeing what was taking place with the Arab spring, with Ukraine and Turkey, and felt that there was obviously a contemporary element of history, and history repeating itself, where we could bridge the gap between the past and the present in this virtual form.

Telling a historical story in a video game -- you face similar complications that you do in other mediums -- same as books, films, etc - in that you run the risk of oversimplifying events to tell the story. In making 1979 Revolution, our mission was to tell the story of the people - not recall the top down events revealed in headlines - Shah vs Khomeini - that people already know. In telling the “people’s” story, we aimed to reveal the complicated events, family dynamics, unraveling of social fabric that is often under-represented in history.

This nuanced perspective of the “experience”, the humanity inside the revolution is more about revealing the larger “TRUTHS” of the revolution. 1979 Revolution follows the actual trajectory of the real events between 1978-1980, while the character’s narrative is shaped by the players own choices.

By making this a game experience as opposed to any other form of media, we were giving ownership to the gaming audience of these events. Most people have little to no knowledge of these events, and by forcing players to make choices, and then reckon with the repercussions of those choices through the narrative and events of the game, it felt like it was the best way to portray the sort of "cause-and-effect" chaos that happened all too often during the Revolution itself, and showed how things that begin one way, in a very small decision, can grow and spiral in unpredictable directions.

We took great lengths in our research (using primary resources -- conducting our own interviews - in addition to secondary sources), in our choice of advisors (we were fortunate to find the best in the world from scholars who study the patterns of revolution, like Jack Goldstone, to Political Scientists like Karim Sadjadpour, to Photojournalists who were on the streets during the revolution like Michel Setboun).

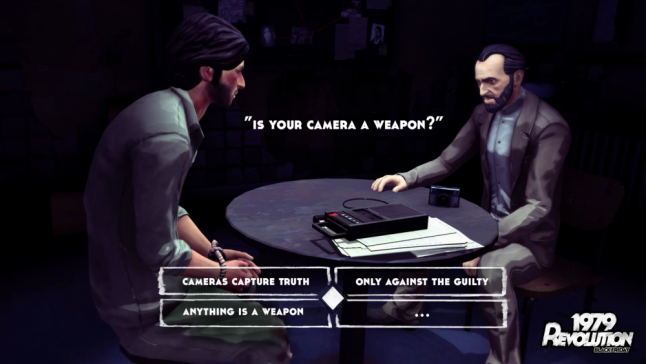

Our environments, art, characters, photographs, stock footage, graffiti, speech recordings used in the game are all either the actual/original assets or they are used to be specific references. Because we did this, we felt like making the player a photojournalist was a really strong gateway into this world we had collected so many archival resources about - not only could we bring these into the actual design of the game, and thus show people that they are playing through these real events, real streets, real days and so on - but we could give them an "objective" point of view, slightly detached at first, and let players wrestle with the choices of objectivity vs subjectivity for photojournalists.

When do you put down the camera & pick up the rock? Or is a photo a stronger weapon than a gun? All of these were really philosophical/moral questions we felt were really juicy and interesting to give the players real agency and drama in the storytelling.

Choice is probably one of the strongest elements of engagement you can use, and it's one of the reasons gaming stands above other forms of media as the ultimate personal experience. For us, the elements of player agency and choice were counter-balanced with an actual emphasis on the "real events" of 1978-80 occurring, and so the choices you were making had to be a on a much more personal, micro level than impacting the entirety of the course of the Revolution.

In the end, we think this was a much stronger choice than going "big" because it meant you could impact the relationships/fates of friends and family you care about, who in turn, are sort of representations for the larger groups and societies of Iran at the time. By making these symbols evident as personal characters you grow to care about and fight with at times, it felt all the more engaging. And by letting players bring their own moral barometer's into this world and "role-play" as Reza, and think how they would have navigated and survived this tumultuous world, it brought more ownership to the narrative, and gives every player the opportunity to craft their own story in this true world, and have their own fates they have to reflect on, and wonder how/what they could have done differently.

Inside - Big fan of the work of PLAYDEAD. Old Man's Journey - We were with them at PAX 10 and really happy to see the game get recognition. Hyper Light Drifter - Was with us at Indiecade and is just this really good, energetic game experience.

Digital Distribution has been key in bringing more indies to the market. The gate keepers in distribution and the need for actual physical games are no longer needed. That, combined with more and more gamers embracing the fresh content and approach to design that we are seeing in the Indie world is making this still a great time to take risks and break new ground in gaming.

As for hurdles, that hasn't changed - it's still finance and marketing. You need time to craft something that is going to have impact - so you need the runway to do some proper R&D - to make mistakes and to grow from it. Once you have made something you need people to know about it so they can try it. Getting it in front of people has become a huge challenge and with the huge $$$ being thrown by user-acquisition focused apps and the big marketing budgets of AAA, it makes it very hard to get access to that limited time that folks have dedicated to games.

I think for us, personally pushing our real world/middle east focused content has been challenging as we are the first to introduce people to a new genre and then the actual content that we are making. Having a large publisher like Sony and MS making diversity content as a mandate will be key in allowing the indie scene to expand its reach and allow it to become a truly global community.

Overall I am optimistic - 1979 Revolution: Black Friday started off slowly but has gained much momentum thanks to Indiecade, PAX 10 and other supporting Indie advocates and fans.

You May Also Like