Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

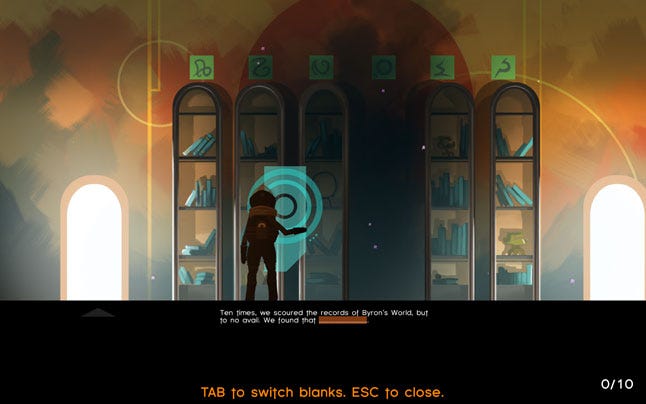

There's an awful lot of discussion about the right approach to narrative in games. Elegy for a Dead World's approach is striking. It asks the player to collaborate in the creation of its story.

There's an awful lot of discussion about the right approach to narrative in games, and several of this year's IGF finalists earned their place among those ranks because of their approach to narrative.

Elegy for a Dead World's approach, of them all, is striking. It asks the player to collaborate with the very creation of its story -- by typing directly into the game and thus shaping its very subject matter.

To find out just how this works, Gamasutra spoke to Ziba Scott and Ichiro Lambe for a window into the creative process.

What's your background in making games?

Ichiro Lambe: I started creating games as a hobby in the early '80s. I had a TI 99/4A, which I eventually took apart when I moved on to the Atari 800. During college, I worked in the industry on and off, eventually founding Dejobaan in '99. We're probably now best-known for our BASE jumping game, AaaaaAAaaaAAAaaAAAAaAAAAA!!!, our first-person bullet-hell shooter, Drunken Robot Pornography, and now Elegy for a Dead World.

Ziba Scott: Playing games turned into studying computer science, which turned into Linux consulting and web development. Linux and web dev made me boring at parties. Talking about your struggles writing financial forecasting software isolates you from people. I wanted to come home from work and tell my wife I was able to get 75 percent more lizard-men on screen. So I took night classes and got a Masters in "Serious Game Design." I quit my job in 2010 and have been the sole proprietor of Popcannibal ever since. I love playing violent games, but I'm not that keen on making them. So I've focused on more novel forms of interaction like happiness and writing.

What development tools did you use to build Elegy for a Dead World?

ZS: Unity. Spine for animation. Photoshop. Gimp. Git. BitTorrent Sync. Dropbox.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

ZS: About a year on and off.

I'd love to know how theme played into the game. In other words, why did you pick the theme you did, and was it designed to get people into the idea of writing?

ZS: The kernel of Elegy formed around the idea of wandering through an abandoned place (like in Rendevous with Rama). We drew from Romanticism (British, specifically) to give us coherent, but varied feelings across our worlds. Romanticism is about nature and the sublime. Shelley, Keats and Byron each wrote about end times. Specifically the end of a kingdom, a life, and a world. William Turner's paintings like "Wreckers Coast of Northumberland" have a quality that inspire a strong feeling of place while inviting your interpretations.

How did you come up with the concept?

IL: Elegy started off as an urge for Dejobaan to take a break from two larger projects (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby and Drunken Robot Pornography) and to work with Popcannibal. Over the course of a week, we prototyped a side-scroller where you simply walked to the right and took in scenes of long-dead civilizations. It was Ziba's idea to draw from British romantic era poetry, as the themes of the above poems fit ours nicely.

How possible is it to turn writing into a game mechanic?

IL: This is where cross-pollinating with other game developers is invaluable. We were sitting in the kitchen of Michael Carriere's Indie Game Collective by Michael Carriere (the Collective being a sexy game dev co-working space in Boston), sketching out game scenes on 8.5"x11" pieces of paper. We bodily pulled aside a fellow developer, sat him down in a chair, and showed him our sketches sans descriptive text. We then asked him to tell the game's story based on those sketches, figuring that he'd pretty much tell us our own story back to us. He totally didn't.

Instead, he spoke aloud, interpreting everything in context, weaving his own (internally consistent) narrative. This statue over here was obviously a popular politician. That machine over there was obviously a weapon. It slowly dawned on us that we should be creating a game where the player is the one telling the story.

I'd love to know how successful this project was — however you define that. How close did the game come to your initial creative goal, and how did people respond?

IL: We did a lot right, and some things wrong. Our Kickstarter hit 150 percent of its goal, and resulted in a game that launched three months ahead of schedule. The press covered us consistently through development, and we received nice pieces from Wired, the LA Times, and many more. Heck, Hulu had our trailer up there right next to Call of Duty, Alien Isolation, and Grand Theft Auto V. Not too shabby.

Reviews were mixed. Some reviewers absolutely loved the idea of a title with nontraditional play, while gameplay-centric folks didn't care for the lack of explicit mechanics. Had we to do it over again, we might have tried harder to satisfy that crowd more. However, Elegy's received a generous portion of critical acclaim, having been a GDC Experimental Gameplay Workshop and IndieCade E3 selection, IGF 2015 finalist, and so forth.

As for our initial creative goal: the original vision was to create a game where you walked around and took in the scenery, and we ended up with a game you play by writing fiction and sharing it with the world. That evolution was really satisfying.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

ZS: I've not played nearly as many of them as I'd like. Especially since those that I have played really shine. (Desert Golfing, Bounden, How Do You Do It?, Ephemerid, Framed)

IL: If Bounden were to trounce us for Nuovo, I wouldn't be mad. It's a game about dancing ballet, and Adriaan de Jongh is a badass genius for making it.

What do you think of the current state of the indie scene?

ZS: From my limited vantage point, I see it growing and changing. Which is the best way for most things to be. There is more uncertainty, anxiety and disappointment than I'd like there to be. But the overall feelings of support, common goals and good will that I get from other developers more than makes up for that.

IL: Call it the "Third Age of Indies," first with the shareware days leading up to the mid '00s, and then a golden age with iOS and Steam first on the scene in the late '00s and really evolving in the early '10s. Now things have matured to the point where gamers are comfortable with the concept of smaller games, and the major marketplaces are opening up to accept many more creators. I think we'll see increasingly divergent groups of a) bedroom developers who just want to create things, damnit, and b) independent studios who look at things as a small business first and foremost.

You May Also Like