Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

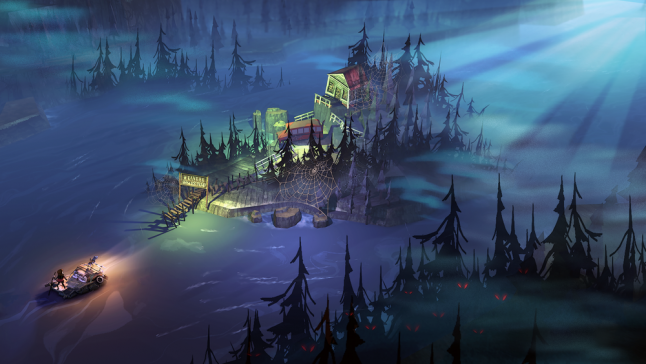

The Flame in the Flood takes players on a river raft journey across the backwaters of a post-societal USA, tasking them with surviving the wildlife, natural disasters, and rapids of their journey.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

The Flame in the Flood (TFITF) takes players on a river raft journey of danger and survival across the backwaters of a post-societal America, tasking them with surviving the wildlife, natural disasters, and rapids of their journey. With only a dog companion by their side, players will need to forage for the tools, food, and items needed to stay alive in this world of constant danger.

The Flame in the Flood put its sound and visual styles to work strengthening the experience in different ways, setting the mood with music and creating a sense of contrast between the harshness of survival with the game's lighthearted look.

These thoughtful decisions involving audio and video earn TFITF nominations in both categories from the Independent Games Festival, and Gamasutra spoke with Forrest Dowling, lead designer on the project, to talk about how the team deepened the mood of fear and hope through sound while also making a difficult adventure easier to take with visuals.

I’ve been making games professionally for the last 10 years, and made mods for a bunch of years before anyone was willing to pay me to make them professionally. Most of my career was working on big, expensive shooters: Frontlines, Homefront, and most recently BioShock Infinite. I’ve been a level designer throughout.

The concept was born from 2 simple ideas: I wanted to make a pared down survival game that focused on the mechanics of real-world survival, and Scott Sinclair (Sinc), our art director, wanted to make a game that was based on the idea of exploring tiny worlds. Those two things were merged and developed into the final game, with the tone, setting, and music all coming together to support those initial goals.

We used Unreal Engine 4 for the game, along with FMOD for audio. Outside of that, it’s the usual suspects: Adobe Creative Cloud, Max and Maya. Our animation and rigging was all Maya, and all the modeling was done in Max.

We spent about 20 months from inception to ship, and have spent a few more months in total post ship with additional support and patches.

Part of the initial idea for TFITF was to bring Sinc’s illustration work to life. Prior to working on games, Sinc was an accomplished editorial illustrator, and has always pursued painting outside of work. TFITF is probably the closest realization of his personal style in a game thus far. We also wanted to contrast what we knew was going to be a pretty grim experience with a colorful presentation. I’ve always been a fan of that sort of contrast, and felt that it would help prevent the overall experience from feeling too oppressive or depressing for players to spend hours inhabiting.

Our approach to the soundtrack was to work with an artist who was already in the tonal range that we were looking for, and give them free reign to work within the thematic area of the game. We gave Chuck Ragan (the musician who wrote and performed the soundtrack, along with a group of his regular collaborators) a word cloud of the sorts of things we wanted to invoke in the game, the feelings and experiences, and he used that to write everything.

A lot of the feelings we wanted to invoke revolved around the central premise of being lost in the wilderness. Some tracks were intended to capture the intensity of bombing through rapids, others the desperation of feeling your supplies diminish as the world ceases to provide.

The addition of the dog friend had less to do with survival and more to do with combating the loneliness we thought the player may feel, and because we felt right from the get go that playing as a girl with her trusty dog friend was the sort of iconic experience that we wanted to capture. There probably aren’t great logical reasons behind it, just more emotional ones. Sinc & I both have and love dogs, and it just felt right.

I think there were a lot of challenges there, some that we tackled better than others. I put a constraint on myself early on that everything needed to be grounded in real world survival, which we needed to veer away from in certain instances where there is no real world solution. If you get bitten by a water moccasin in the wilderness, you mostly just need to hope for the best and probably die. That’s not really a good experience for a player.

Given the limits on the available tools that this approach created, the biggest challenge was figuring out an ecosystem of solutions for given problems, but ultimately they all need to make sense to some degree, and feel natural based on a person’s understanding of the world and how wildlife works.

Looking through the list, I’m realizing I’m a bad person in that I’ve only played Inside, although there’s a lot that I’ve wanted to check out. So to comment on the only one I played: Inside was a masterpiece in every way. As someone who’s career is grounded in level design, the tightness of the scripting that was on display was a thing of beauty for me… specifically the numerous perfectly engineered near-misses and moments of tension that are player-driven but utterly perfectly authored.

I think the biggest hurdle is getting noticed in a sea of constantly releasing games - against an ever growing back catalog of great titles. People only have so much time and money, and the rate that games are releasing is increasing dramatically while the audience is not. It’s tough and I don’t have answers for any sure-fire solutions, aside from make the best possible stuff and look for gaps in genre that are presently underserved or non-existent.

As far as opportunities, I would say that if one is willing to trade independence a bit, there are growing opportunities in the mid-tier of budgets that bottomed out for a while midway through the x360/ps3 cycle, during which the only game being made were sub-$1 million budget or over $50 million. I think publishers and consumers are starting to embrace titles that are interesting and innovative, but maybe lack the ultra-polish of a major AAA release.

You May Also Like