Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

These days, many games feature a blend of action and RPG elements -- is there any way to determine whether a blend is effective? Is there any way to think about the specific target you're aiming for? Game design analyst Josh Bycer takes a stab at it.

[These days, many games feature a blend of action and RPG elements -- is there any way to determine whether a blend is effective? Is there any way to think about the specific target you're aiming for? Game design analyst Josh Bycer takes a stab at it.]

One of the key areas of evolution in game design has to be the merging of genres. Games like the Uncharted series combine shooting, puzzle, and adventure elements together.

Besides expanding the gameplay, this serves another purpose; it opens up the game to more people.

Two genres that have been working the hardest to do this would be action games and RPGs. The determining factor is the abstraction of skill and how each game handles it differently. This has lead to the term "skill abstraction." It's defined as:

The degree of which player skill (or input) has an effect on the gameplay.

In their infancy, both genres existed on complete opposite ends of the spectrum. Slowly, over the years, games designed for both genres have been moving inward. Action games have been adding more RPG elements; RPGs have become more action oriented.

On one hand, this has opened up the respective genres to more gamers. However, to quote Abraham Lincoln, "...you can't please all the people, all the time."

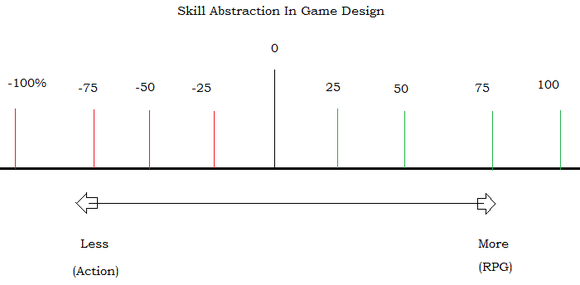

Before we examine this, here is a chart showing this abstraction:

-100 percent refers to games with zero abstraction of skill. These are games where player skill is the only determining factor in beating the game. For instance, early shooters didn't deal with the concept of in-game accuracy; if your cursor was on the enemy, you were going to hit them. Gun games, popularized in the arcade scene, are another great example. How well the player can aim the gun and prioritize threats were the only factors that separated victory from defeat.

-75 percent brings us to modern day shooters, where factors like the characters accuracy and movement now play a role. You can't expect your character to fire well while running and jumping, this also gave rise to the importance of cover. Skill is still important, but now the player must balance their skill with the additional factors of the character.

-50 percent is where all guns are not created equal. Games like Stalker, Call of Duty, and even Team Fortress 2 feature a variety of weapons. In Stalker, there are multiple pistols, shotguns, and assault rifles, but they are not only differentiated by type. Guns vary in terms of how much damage they do, their accuracy, and so on. Even though the player may be a crack shot, if their gun has poor accuracy, they may not be able to hit enemies or do enough damage to kill them.

Team Fortress 2 has embraced this concept, with all kinds of equipment available. Different guns for the classes have different effects, and give the player more options on their classes' load-out.

-25 percent has been recently popularized thanks to Borderlands. Billed as a "role playing shooter," the game features the same kind of weapon diversity seen in games at the -50 percent mark. Combat is still twitch-based, and getting a hit on the weak spot of an enemy will cause more damage. The key difference is that now the player has their own experience level to contend with.

The leveling system works like this: if both the player and enemy are the same level, then there are no modifiers done to damage on either side. If the player is a higher level, they will receive a damage bonus based on the difference in levels, and the enemy will receive a damage penalty when attacking the player. The effects are reversed if the player is a lower level compared to the enemy.

The other end of the spectrum:

100 percent abstraction. The first CRPGs and tabletop games fall into this category. Here, the only interaction the player has with the game is issuing orders to their party or character. From there, equations and the character's and enemies' attributes determine the outcome of the battle.

75 percent is the standard combat model for MMOs like World of Warcraft or EverQuest. Players can control the movement of their character as in an action game, but all combat and interacting with the world is abstracted by the game.

Players are still restricted to just issuing commands to their character and then watching how everything plays out, but at a quicker pace then the 100 percent titles, due to both parties performing their actions at the same time.

50 percent is where more action elements begin to seep into the design, as evident in games like the first The Witcher. Players can control their characters freely, and this has a greater impact on how combat plays out.

In The Witcher, they can time mouse clicks to form basic combos. Most of the design is still abstracted; the character's attributes, weapons and level are still the prime factors in how combat plays out.

Many JRPGs, such as the Mario RPG series, have also gone this route. Players can influence their offensive and defensive abilities with timed button presses during combat. Combat is still abstracted, with the stats and equipment of the characters the determining factor.

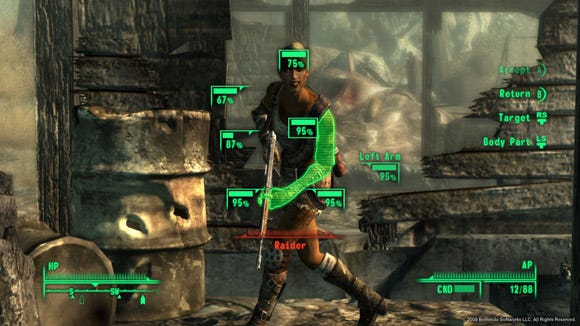

25 percent titles cover a very specific type of RPG. This category includes European RPGs like the Gothic series and has been popularized by Bethesda Softworks with The Elder Scrolls series and Fallout 3. In these titles, the player controls their character much in the same way as in an action title. Combat is real-time, requiring the player to dodge projectiles as they would in an action game, while targeting enemies with their attacks. Once the player makes an action, whether that is firing a pistol or trying to pick a lock, the game abstracts those results.

Fallout 3

In Fallout 3, once the player has their gun lined up with the enemy and fires, several factors come into play: the character's skill with the type of gun and the accuracy of the gun itself both determine if the bullet hits. Once the bullet hits, the enemies' resistances and armor determine how much (if any) damage is actually done.

The player has a variety of choices on how to handle situations, such as convincing someone to help them, or picking a lock. However, once the action has been selected, the rest is up to the stats of the character. For instance, the lock picking mini-game in Fallout 3 is not accessible unless the player has a high enough lock picking skill to begin with.

Before we talk about 0 percent on the chart, it is important to point out the similarities between the two 25 percentile groups. Both types of titles give the player freedom when it comes to movement and setting up combat. The difference is where the abstraction comes into play. Both of our example games, Fallout 3 and Borderlands, abstract damage based on the weapons fired and who is being attacked. Where they diverge is that Borderlands relies on player skill to the point of impact, whereas Fallout 3 is requires only that the player lines up the shot.

As we move to 0 percent on the chart, the lines between the genres begin to blur. Games like The Witcher 2 or the ultimate direction of the Mass Effect trilogy are examples of this. At this point, the traditional description of the genre is not enough to describe these games.

The Witcher 2 uses both skill and abstraction throughout its design. During combat, the player has complete control of the main character, Geralt. Whenever the player lands a hit, either by sword, item, or magic, the game will run calculations to determine how much damage was done. The majority of Geralt's abilities are locked behind the leveling system, such as adding more functionality to his spells, or the ability to counterattack.

Leveling up allows the player to choose which skills, or traits, to improve which will affect his abilities in combat. During conversations, the game will abstract the results of choosing different negotiation options like threatening or mind control. These skills will level up on success and increase the success rate for future choices. Combat is where the bulk of the gameplay is, while the interactions with the characters of the world determine how the plot plays out.

For a game like The Witcher 2, or with how Mass Effect 3 is shaping up, do we refer to them as action games with RPG elements, or RPGs with action elements?

By casting a wide net with their designs, developers and publishers are chasing the dream of creating games as close to 0 percent as possible. However, as designers move away from the extremes, they risk alienating their core audience.

Times have changed in the industry, thanks to games becoming more mainstream. Core gamers, or the ones who want either -100 or 100 percent abstraction, are no longer the majority. Instead, they have for the most part been moved into a niche market, as most triple-A titles are aiming for greater appeal.

Most skill-based games are aimed at the -70 to -50 percent crowds, while RPGs are aimed at 70 to 50 percent. A distinction has to be made: it's not that these fans are going away; instead, they are a drop in the bucket compared to the fans of more mainstream games.

When developers and publishers see series like Call of Duty, Mass Effect, or The Elder Scrolls on the top of the bestsellers list, and recipients of numerous awards, that has to catch their attention. This has led to the challenge of creating games that appeal to everyone. However, if there is one lesson to take away from this article it is this:

You cannot make a game that has universal appeal.

Design-wise, it is impossible to create a game that relies on 100 percent player skill and at the same time completely abstracts character interaction and expect it to appeal to everyone.

Skill-based gamers don't want to have to grind levels so that their headshots will do damage. Conversely, RPG fans want their character's dexterity, not their own, to determine outcomes. Something has to give; one side has to be given priority in the game space -- and when that happens, someone is not going to be happy.

As a designer moves closer to 0 percent, they need to realize that genre conventions and mechanics will either not fit, or have to be altered. A UI for a -100 percent game doesn't have to be complex. With Bulletstorm, the only information on screen is health, ammo capacity, and score. As more abstractions are added to the design, the UI needs to be redesigned to accommodate them -- such as an indicator for accuracy, and even an inventory screen.

Strict control of a party in a RPG becomes harder with less abstraction. A player simply cannot give the same complex orders when everything is real-time. This requires the designers to give more AI control to the party, or change the player's role during combat, from tactician to fighter.

Another challenge is that players have expectations for the respective genre. Action games are about presenting information as cleanly and easily as possible to keep players in the action. On the other hand, in a RPG where managing attributes and information is necessary, the player wants to slow down and examine the data. As the design moves to 0 percent, these two polarizing views will have to be dealt with -- and if it isn't done right, it will annoy fans of each specific genre.

The Witcher 2

Take The Witcher 2, as an example, in order to find information relating to the RPG side of the design, such as the level of their conversation options. The player has to go through at least three different screens' worth of information. This slows the game down dramatically, and is a sharp contrast to how responsive combat is.

The Stalker series, on the other hand, developed a UI that achieves a greater balance between action and abstraction. The inventory/status screen gives the player all the information they need about their character, including details on their weapons. This allows players to find what they're looking for, make any changes, and get back to the action as quickly as possible.

Mainstream game design has become a game of tug of war between keeping the fans (or core gamers) happy, while expanding the appeal of the game with the designers caught in the middle. Pulled too far one way and you have a game that keeps the fans happy, but has limited appeal. Go too far the other way and the designer can have a worse situation: a game that is too watered down for fans to enjoy, yet too inaccessible to attract a larger audience.

The industry is now at a point that it has entered the mainstream, much in the same way that comics and rock music have done before. In this new reality, it will be up to designers to strike a balance between old and new fans.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like