Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra's Christian Nutt plays the 1997 original and considers what lessons the nearly 20-year old game, soon to be remade for its anniversary, holds for the game developers of today.

Over the holiday, my husband and I played through a nice big chunk of Final Fantasy VII -- the original 1997 PlayStation release. My reaction, and I was skeptical to it at first, was that this is a very good game that is still a pleasure to play; the next thought that came once that realization sunk in, however, was that it's going to be a real challenge to reproduce what makes this game great in that HD remake slated for 2017.

Sitting down to give the game serious time and undivided attention gave me the chance to reflect on not just what it accomplished creatively and technically at the time, but how it holds up, as a game, irrespective of when it was made -- or its landmark status in the industry.

That is, naturally, hard to put to the side; however, it's a lot easier to do it when I flash myself back to 1997 and recall that, at the time, it had to earn its reputation. Taking the game at face value, rather than viewing through a lens of nostalgia and consensus, is essential. And it's a lot more fun than carrying a bunch of baggage.

Final Fantasy VII makes a good first impression. The game's in medias res intro sequence -- it begins with an infiltration mission, underscored by a dramatic soundtrack -- is among the best in not just the genre but in games, even now; it's a game that that entices you to play from moment one. It only slows down once it firmly establishes itself.

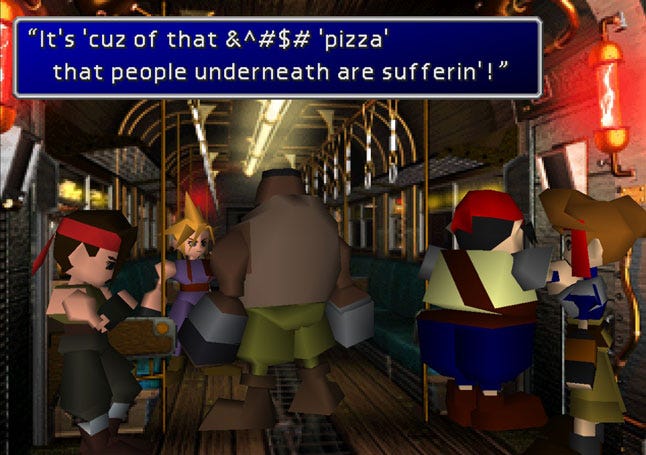

While the plot has a reputation for being esoteric, I think the latter-day Final Fantasy VII spin-off projects of the 2000s are what muddied the waters. The original game is, actually, quite easy to understand. Take the intro: Members of a resistance group called Avalanche conspire to plant a bomb in a power reactor with the help of an elite ex-soldier, Cloud Strife, controlled by the player; he doesn't care about their politics, but he's willing to help out for the money, and, it later becomes clear, because a childhood friend roped him into it.

The cause of his alienation from his former employer, the Shinra Electric Power Company, quickly becomes apparent. The clarity and purpose of the storytelling is striking. Triple-A games too often either boil things down way too far in attempt to make them comprehensible, or complicate things unnecessarily. The former is usually based on the assumption players don't care and won't remember the plot; the latter speaks to an infatuation with setting ("lore"). Final Fantasy VII's setup, meanwhile, is rich enough to be interesting but simple enough to follow with ease.

This screenshot is from the PC version of Final Fantasy VII, as are all the large images in this piece.

While the setting is surprisingly robust, especially compared the baroque and increasingly nonsensical backdrops of the last-gen Final Fantasy XIII trilogy -- try getting anything useful out of the intro for Lighting Returns -- it's easy to get lost in.

And in an era of real-world income inequality and ecological crisis, it's also surprisingly potent and directly relevant in ways mainstream game stories rarely are. It's not hard to imagine downtrodden ecological warriors taking on an exploitative power company that's destroying the planet. We may be headed there ourselves.

What's fun to recall is that the game's opening was generally considered strange in 1997: The player can't get out of Midgar, the city where the opening chapters of the game take place, for several hours. It was viewed as highly un-RPG-like to not let the player explore the world for so long.

Yet what you see of the city itself, and how the underclass of Midgar lives, helps the setting come to life in a way that's still rare. Nowadays, spending time and care to develop a single location doesn't seem strange at all, but the way in which Midgar is evoked is something we could use more of.

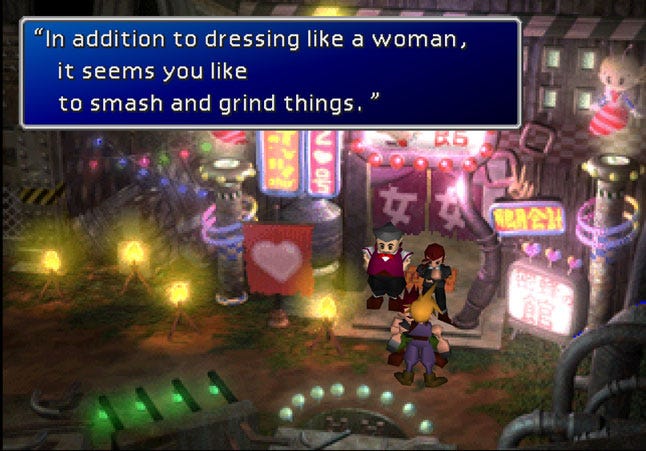

The Wall Market's brothel.

While the developers of the forthcoming remake of the game are still being coy about whether or not it'll be an open-world RPG, the strength of Final Fantasy VII is that Midgar comes alive in a highly impressionistic and idiosyncratic way; you can visit only a small slice of the "rotting pizza" that makes up the metropolis.

Rather than spend time modeling dozens of buildings and the ebb and flow of the crowd, under influence of Assassin's Creed, I'd rather see the developers of the new game spend time figuring out how they can recapture the colorful neon glow of Sector 6's Wall Market. In the real world, we generally only know neighborhoods well, not whole cities, after all. One tragic, crumbling section of Midgar would be a real artistic achievement.

Final Fantasy XV lead Noctis. "I smolder."

Mentioning the Wall Market makes it a good time to discuss something significant, which is easy to forget, these days, as Final Fantasy XV lead Noctis glares at us. Final Fantasy VII is a funny, lively, and very random game; the Wall Market is the setting of the infamous scene where Cloud dresses as a woman to sneak-attack a notorious womanizer and save his friend Tifa.

But is a scene like that even possible in a modern retelling? I don't mean because it's out-of-step with today's social mores (though this is, of course, significant.) I mean it in the sense that the original game's theatrical style and comic spirit seems most likely to be jettisoned in an attempt to make a more photorealistic game, and to live up to the series' current-day, self-serious image.

The Final Fantasy of the 1990s was steeped in humor, both gentle and overt; of late, the games have gotten more bombastic and pompous. The majority of the humor in the largely nonsensical 2005 Final Fantasy VII film, Advent Children, was inadvertent. If anything, things have gotten worse since then. What little comic relief there is, is generally cringe-worthy, even perplexing.

I'm talking about humor here, but what I really mean is broader than that. What I'm talking about could be called "humanity," maybe -- spirit and verve. Final Fantasy VII has a lot of all of that, and it comes across in a lot of different ways. With its tale of a world divided, the original Final Fantasy XIII tried to recapture the tragedy of Midgar, but it got lost amidst a tremendously artificial setting that did a great job of painting hallways of frozen crystal and glowing trees but completely failed to portray any cohesive (or comprehensible) world at all.

At least it's pretty.

Sure, Cloud is as cool as frost, and he's definitely got fabulous hair, but without photorealistic rendering, the focus in 1997 didn't zero in on the protagonist and his party. An eclectic spirit underpins the creativity of Final Fantasy VII; Final Fantasy XIII director Motomu Toriyama told me how the studio finds the democratic, collaborative development style of the older games nearly impossible to execute in its modern, huge-scale productions, but it's going to have to figure out a way to do so, or a remade Final Fantasy VII will end up as simply another fashion show. Without humans, there is no human element.

Playing the game today, I was struck by something else. In 1997, I took for granted the creative through-line of the Final Fantasy games. The high-spirited, character-driven storytelling style pioneered by Final Fantasy IV became the beating heart of Final Fantasy VI; its ambition is clear, yet clearly bounded by the limits of the Super NES. Final Fantasy VII was the direct inheritor of that mode of storytelling, with vast and rapid improvement coming simply by freeing it from those limitations. Final Fantasy VIII was, of course, a simple refinement of what began with VII.

The lesson of Final Fantasy VII, then, is that it was possible to revolutionize a franchise, and what it accomplished creatively, yet stay in step with where it had been in the past. It's good advice for anyone who's working on a game in a long-running series.

That would include Square Enix's developers, though it's hard to see how that's remotely possible for Final Fantasy now, since instead of a steady march, the franchise's last decade-plus has been a cacophony of distinctly different voices.

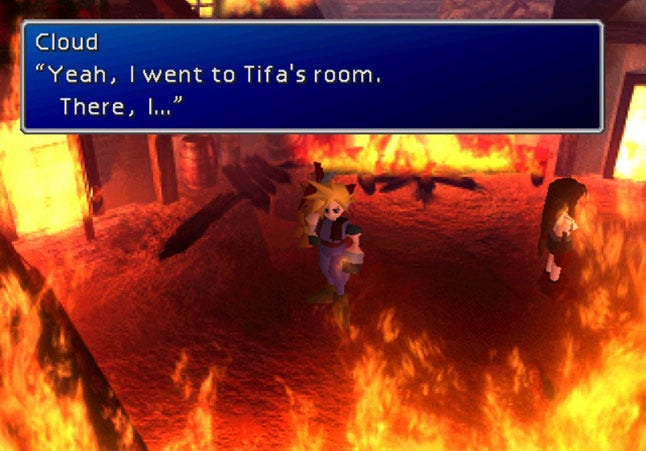

I haven't finished talking about the things that made me sit up and take notice. I talked about Final Fantasy VII's very beginning, and how effective it is, but the first significant sequence after you leave Midgar, in which Cloud recounts his memories of the Nibelheim incident, where Sephiroth goes on a destructive rampage, is also clever and effective storytelling in a different way. It sets up the big bad and his motivation, of course; it provides context, shading, and motivation to Cloud and Tifa, too.

Cloud's memories unravel.

But it also plays with the subjectivity of the narrator and interactive narrative in surprisingly effective ways. Cloud is an individual, and his experiences are his own; his memories of them, as he recounts what happened five years before the events of this game, are necessarily limited and unreliable, too.

The game communicates that through play. There's a point where you, as Cloud, can make a joke (in the form of a humorous lie). There's another part where Tifa corrects something Cloud misremembered. There's also part where you enter a house and then realize you never even went there at all. And in the midst of all of that, the game tricks the player, too, in a much more significant way -- that only becomes clear much, much later.

We need much more of that kind of storytelling in games -- personal, fragmentary, and related as experience. In fact, the game's frequent mixture of in-engine, on-the-fly storytelling with animated backdrops and relatively rare full-video cutscenes results in a livelier pacing that has fuzzy borders between narrative and play, and which flows much more naturally. In fact, it helps deliver storytelling that works much more like film than the "cinematics" we're so used to seeing, but which owe little to moviemaking.

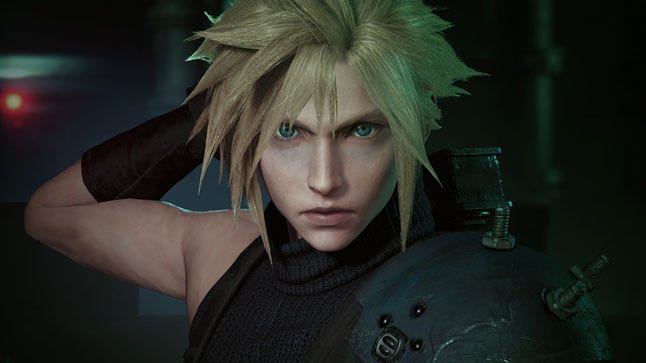

Cloud, circa 2017.

Years ago, I wrote about what Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII got right. To be blunt, as a game, it's not great. It's simplistic, easy, barren. It certainly can't compare in scale or scope to Final Fantasy VII. Somehow, it's still the best Final Fantasy game released since the PlayStation 2. That's because it didn't forget that characters are the soul of the franchise, and tied their stories directly into its gameplay.

No matter how repetitive its dungeons were, or how irritating and superfluous its antagonist, Genesis, was to Final Fantasy VII -- and how all this presaged the creative downturn of the franchise, since it's at cross-purposes with its strengths -- Crisis Core still managed to strive for something. Leaving all its weaknesses to the side, Crisis Core's climax was unforgettable, and worthy of the franchise's creative heights, in a way that nothing since has been.

It's very hard for most of us to remember a time before Final Fantasy VII. Hell, it's getting hard to remember the time before "triple-A," before big games were expected to tell big stories. In that light, it's almost funny to think that the original Final Fantasy VII kick-started the industry's infatuation with cinematic storytelling -- because these days, I think the lessons it would best offer modern game developers would be to pare down, to get looser, to be less worried about visual panache and more interested in creative texture and less interested in cinematic narrative tied in a tight bow.

Two screenshots of the original PlayStation game, sourced from websites whose image galleries still stretch back to 1997: GameSpot and Shacknews.

Take, for example, the game's battle graphics. They're still beautiful, actually, and that beauty is much aided by the fact that the developers couldn't get within spitting distance of any kind of photorealism. The characters and enemies are barely textured, constructed in flat colors and mostly simply shaded.

Final Fantasy VIII: A little harder to take. Images from GameSpot's gallery.

Because Final Fantasy VIII strove to look so much more realistic, it's harder to take seriously now -- even if it was a big step forward at the time. VII, meanwhile, retains a rough-hewn cartoony spirit, with gentle curves; details are saved for the features that most make the characters stand out. They all have unique silhouettes.

In fact, I'd even argue that the hi-res version (for PC and PlayStation 4) which reduces the roughness of the low-res polygons (and loses the PlayStation's signature Goraud shading) actually degrades the game's visuals. We ended up giving up on that version quickly and retreating to the original, however imperfect it might seem today.

The fact that the developers of Super Smash Bros. chose to base their portrayal of Cloud most on his original Final Fantasy VII incarnation makes my argument for me, I think; it's not just nostalgia, but a recognition of the effectiveness of that first incarnation of the character. Sure, they acknowledge what came later through myriad small details, but the bearing of Cloud Strife in Smash Bros. is that of the original.

The fact is that the original game achieved an uneasy sort of perfection by being at the intersection of the old and the new -- the original PlayStation opened up wide new horizons for game creators, but those creators were not, themselves, blank slates.

I want to see Square Enix fight, again, to give the series heart and hope and light, all of which are sorely missing from it these days. They've been replaced with a sort of lazy self-confidence that somehow never seems to be shaken no matter how bad things get. When the next numbered game in the franchise was announced 10 years before it ships -- even accounting for the fact that it must have been started over from scratch during that period -- things have gotten bad to a degree that is essentially unprecedented in the game industry.

But I think the thing I most want to call attention to is the fact that Final Fantasy VII is fun. It is simply fun to play. It's fun for reasons I've already discussed (the narrative being speedy and well-integrated with the gameplay is one; the game's sense of adventure and panache another two) but also because it is, at a basic level, a video game.

Though it is Patient Zero of the cinematic pretensions of modern video games, it turns out that Final Fantasy VII is anything but a movie briefly punctuated by interactivity; it's an accessible RPG that has just enough gameplay depth to sustain itself and is fast-paced enough that you won't get bored with that simplicity. For all of its awkwardness -- and yes, we perceived this awkwardness in 1997, too -- it is quick when it counts.

I can't help contrasting that against the awkwardness of Lighting Returns; the developers tried to bend the by-then creaking and groaning Final Fantasy XIII engine, which was never very flexible, to new gameplay ends -- stealth and action among them. The game would have been better served if they'd tried to cook up a more straightforwardly simple RPG adventure that capitalized on what that engine could do, reliably, which is not much. The best course would have been to slice off the fat, in other words -- not slather on sauce.

If there's a lesson to learn, I think, that could apply not just to Final Fantasy but any game -- maybe any creative project -- it's to understand what you have on your hands and how to play to its strengths as you build it out. Identify what your game does and, from that, what it should do. This is not a technical question, really. After all, the Final Fantasy VII remake is going to be built in Unreal Engine 4, so there's little doubt that all possibilities are on the table. No, each creative project has its own spirit, one that should emerge through its creation, and that should be listened to.

Each team member has talents. A game's setting has a mood. A game's characters have their voices. It's easy not to listen. In game development, things come together in pieces, and slowly; it's obviously necessary to just push forward and keep building, hoping the project will cohere but being unaware, oftentimes, until very late, whether it will. Final Fantasy VII is, in fact, such a project, in a very obvious way. It doesn't have a consistent look, and segments of its story miss the mark completely. It's a hodgepodge of a game if ever there was one.

But a whole did emerge, and it emerged from a relentless effort to create something fresh. In this era of huge budgets and huge teams with tight specialization, it's difficult to offer developers the same kinds of freedoms. But the right place to start would be to recognize the true strengths of this game from 1997, to truly understand and embrace them, and to make creative decisions with that spirit in mind. I don't mean just for the developers of the remake. I mean for anyone. Sit down and pick up a game that you barely remember, but you know is good, and play it with eyes afresh. Analyze it.

The original Final Fantasy VII had a scope that allowed for experimentation on a scale that is simply impossible in the modern, triple-A era. I think that an argument can be made, consequently, that the right direction for Final Fantasy isn't triple-A in that sense, but it's clear that ship has sailed, and the dock has been burnt down, too. So instead, what is deeply necessary is that the developers take the lessons of the past to heart, think critically, plan carefully, and then allow themselves whatever creative opportunities are actually possible as they arise.

Taking into account that Final Fantasy VII's director and the series' current main producer, Yoshinori Kitase, has been priming us for the fact that a true remake of Final Fantasy VII would be impossible for years, and considering the games that the franchise has produced of late, it's obvious that whatever hopes we might have for this new version must be scaled to match reality rather than our dreams. But that doesn't mean the creative ambition of the team must be. There's pragmatism, and there's just giving up. Lately, Square Enix's games feel more like the latter.

If there's something I'd take away from playing Final Fantasy VII again, it's this: Don't lose sight of your past when you're building your future, and don't forget what games can be as both an expressive medium and as games, constructed of numbers, rules, and systems.

Final Fantasy VII has a lot to teach us, if we're open to it. There's a reason it struck a chord, and it goes beyond the fact that it brought cinematic melodrama to video games on a grand scale for the first time. Its balancing acts -- technical, game design, narrative, and more -- offer suggestions of the form games can take, not just the form they briefly did nearly 20 years ago.

You May Also Like