Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In today's cover feature, Gamasutra catches up with Harvey Smith (Deus Ex franchise, now at Midway Austin) on what next-gen might bring, collaborative versus competitive play, and what gaming can learn from MySpace and Digg.

With a long history working for some of gaming's most celebrated developers like Origin and Ion Storm, designer Harvey Smith has had roles on a laundry list of notable PC games such as Ultima VIII: Pagan, System Shock, Deus Ex, Deus Ex: Invisible War, and Thief: Deadly Shadows.

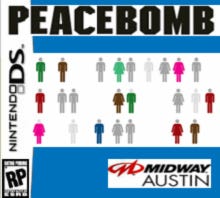

Most recently, Smith made news with his participation in the 2006 Game Developer Conference's Game Design Challenge, where he faced off against Gears of War designer Cliffy B and Katamari Damacy creator Keita Takahashi to create a game that might win the Nobel Peace Prize. His challenge-winning entry, Peacebomb!, was a DS game that organized players to take part in real-life peace and community activist flash-mobs by setting them in a fictionalized game-world underground movement rising up in revolution.

Now a creative director at Midway Austin, we sat down to catch up with Smith on what the next-gen might bring, life at Midway, collaborative versus competitive play, avatar psychology, and what gaming can learn from social community-driven sites like MySpace and Digg.

GS: As we're standing on the cusp of the next-generation, what are you most excited about in the coming years? What more can you do with the technology as a designer now that you couldn't do before?

HS: In the past, I've said "speech synthesis." I've always been so excited about empowering AI's with a wider range of verbal expression, and I still think that'll be meaningful to game designers and AI programmers in the near future. But right now it's a toss up between several things. First, it's exciting to me that some games are moving toward needs-based AI. Especially shooters and RPG's.

Harvey Smith

Second, seamless online elements in games, so that the game assumes that the player is online all the time. I still think there are small roles for all of us to play in one another's games, even in traditional types of games where one player is the center of the universe. For a long time, I've been using the examples of players in a chat lobby being pulled into shooters for micro play sessions, playing the parts of throw-away enemies or even the player-character's semi-autonomous rockets. I've also used the "cell phone players are the butterflies in MMO's" example. Some of that is starting to happen, which is cool.

Finally, for lack of a better term, I'm continually excited about participatory culture's influence on game design. One of the coolest, watershed moments in my career was seeing mod makers create Deus Ex missions, then hiring one of them, Kent Hudson. We're still working together and he's the design lead on one of our projects here at Midway Austin.

And, even as a fan of hardcore PC and console action games, I still hold the often-maligned view that handhelds are the dominant platform of the future. Someday I want a handheld device with a completely realistic screen; something that looks like a little portal into a strange place.

GS: Without divulging classified info, what kind of overarching thematic areas are you exploring with the work you're doing now?

HS: As always, I spend a lot of time split between gameplay and fiction. My role at Midway allows me to bounce around some between a couple of games, though I am also super committed to developing an idea of my own in the background. I've been building up a staff of game designers here in Austin, mentoring the lead designers, setting up the culture, and framing our games. I get to dive in at a lower level from time to time, but my goal is always to make the people around me as autonomous as possible; to align people to a specific vision for a given game and to impart what I consider good, player-centric gameplay values. I've worked on innovative titles like FireTeam, Technosaur and Deus Ex, but I've never really executed with a high degree of polish. I really admire teams that can do that, so my goals right now involve polish and execution.

Thematically, I'm still wrestling with what's going on in the world, in terms of conflict, intolerance, fear and control. So our games reflect that. And, as always, I love playing around with gameplay ecologies; I'm fascinated still by inter-relationships and rule sets that facilitate improvisational gameplay. Doug Church's late 90's talk on Intentionality is still one of my favorite "game designer lessons."

GS: Does your role as creative director even allow you that kind of freedom to set those themes? Or are you more involved with higher-level management?

HS: Management. Ha. I'm a terrible manager. I tell stories. I develop a shared narrative, whatever that means. I sometimes inspire people, sometimes piss people off. And I'm a game designer. Yes, I'm free to set the tone at a high level or go in at a low level and redraw a level layout. When I have to do the former, I'm doing what I'm supposed to do. My goal is to empower people who are in alignment (and can take me farther, teaching me something along the way); working side by side with Jim Stiefelmaier, Kent Hudson and Ricardo Bare (our design leads) is a challenge and the best job I've ever had. They're amazing, strong personalities. When we're in agreement, it's electric. When I have to do something like redrawing someone's level layout on a whiteboard, I go into teacher mode and it generally implies a process failure. But secretly I have the most fun during those times.

GS: Are you satisfied with where you're at in your career right now?

HS: Yeah, totally. We're pushing ourselves hard as part of Midway's new wave. The first next-gen Midway game is Stranglehold and it's stunning. Our games will follow that as part of David Zucker's turn-around. Also, in the background, I have a revolutionary game idea and a cool fiction that I want to work with that is literally keeping me awake at night.

I'm a really lucky guy, given my background. The thing that keeps me most excited about the future is, oddly, the presence of a couple of production leaders at our studio. Denise Fulton, my boss, and Brett Close (from the Medal of Honor games) are, respectively, our Studio Head and Production Director. And my chemistry with them is very motivating.

I'm learning a lot. A lot of satisfaction is related to how you see yourself, personally; how happy you are with yourself; and where you've come from, relatively speaking.

GS: You've previously mentioned that you've got strong opinions on developer-publisher relations. What were they? Have they been mitigated by working for a company that acts as both?

HS: I think it's only a matter of time before online distribution is king. I think some publishers are too risk averse. I think "developing new concepts" is the lifeblood of the industry. Midway is in the middle of something good. You can feel it, working here. There've been turbulent times, of course, but the team surrounding the top execs is really, really interesting. They are on a mission, driven, and they make more sense to me than any previous group of execs.

GS: You've also expressed interest in the past in independent development, which has been heavily in the spotlight lately with Microsoft's XNA Creator's Club, Manifesto Games, and more accessible tools in general--

HS: To me, my technical status as an independent or not has never mattered. It's what I can do that matters. I'm creatively engaged right now, with some very ambitious goals. I'd rather be doing that than working at an independent company doing ports (just to choose an extreme example). For me, it's not about the status of ownership; it's about creative fulfillment and the people I'm working around.

GS: Is indie development moving in the direction you'd like to see? Is this sort of power-to-the-people game creation what you were talking about, or was it a more personal message about leaving Ion Storm and looking for a new career path?

HS: For me, things are generally meant personally. I don't have strong opinions about the way "the game industry" should go. There's a Darwinian dynamic that will drive that. I think, wherever I'm at, people around me and above me have to understand that the best games spring from vision. In short, because someone (or more likely some group) burns to do something for no reason other than finding that thing interesting. There is no better reason to do something than that. Passionate vision, with good execution, will always produce the best games. I think that "good things happening for the industry" will be a second order consequence of creative people doing what they love.

GS: Have you received much feedback about your Peacebomb! proposal from GDC? Have you given it much extra consideration as an actual commercially viable title?

Peacebomb! Mock-Up

HS: Yeah, a lot of feedback has come my way. I can't talk about it, but there's been some cool interaction with a non-profit organization around the subject. After Peacebomb!, I got written up in the NY Times, the Wall Street Journal, and a short time later I was on MTV, doing an interview with Will Wright, Cliffy B., and David Jaffee. I put some pics up and a link to the MTV segment here.

GS: We've seen gaming edging slowly a bit more toward collaborative social and communal experiences -- what more can game designers do to continue to influence this in a positive direction?

HS: Team play is still one of my favorite things. Speakerphone co-op Doom is still one of my favorite experiences. We're including features in our games now that try to facilitate some of those same feelings between players. FireTeam was all about that too. I really think that there's money to be made and good feelings (among players and developers) to engender by specifically building games around features that allow players to aid one another, to build one another up. Beyond giving each other resources or participating in group raids (which are both great, by the way), there's a lot that can be done in games where players specifically, asymmetrically aid one another in having a better play experience, even in action games.

Also, to get to the implicit politics in your question, I think we can score (financially and creatively) by trying to model more diverse subject matter. Okay, we know how to model gun play. Cool. I love it. Guess what, there's a lot of competition there. Maybe we should spend more time advancing models related to social structures: What happens if a handful of players were put in a persistent small town with persistent, memory-driven AI's and the ability to act socially or anti-socially? What would happen if we started modeling more subject matter with universal appeal, requiring less esoteric subject matter; Romeo and Juliet instead of Tolkien. I wish more people would model political or social trends. Or at least we could keep modeling gun play and add some interesting new collaborative tactics; throwing another player an ammo clip in a team-based shooter would be a huge win.

GS: Can gaming take any lessons from MySpace and Digg?

HS: Have you been spying on me? I've been pushing these things (from Friendster forward) as interesting user-driven communities, with far more interesting social interactions than most games. Still, in the end, I love games and simulations. I want to see The Sims meets an immersive action game meets MySpace. Some of the pseudo-MMO's are trying to do this, but aren't there yet. Games can learn a ton from these services or spimes or whatever they are.

At the game writers' conference in Austin recently we talked about avatars and psychology. I found like 12 different Marlon Brando avatars in various chat rooms, each that allowed a user to express something totally different. The self-expression symbologies behind Brando avatars are personal, not globally-significant. Whether people are using Brando-as-Kurtz, Brando-as-Godfather, or Brando-as-Moreau, each user is filling the avatar vessel with personally-meaningful mythology. Games should facilitate more of that human drive, which is the stock and trade of sites like MySpace.

Deus Ex: Invisible War

Deus Ex: Invisible War

GS: Will Wright has recently been talking more about conveying deeper messages in games; how much responsibility do designers have to consider social messages in their games?

HS: I had a super influential conversation one night in a pub in Australia with Ian Bell, creator of Elite (the space trading game). He helped open my eyes to the implicit politics in games. In Deus Ex, the politics we considered were mostly overt, but (importantly) we tried to let the player choose sides. (Later games, like Knights of the Old Republic and Black & White, have also done this.)

But Ian is a smart guy and talked a lot about how Elite reinforced a capitalistic view of profit-as-sole-value, which I thought was super interesting. Even as someone who believes in (moderated) free markets, I don't want to support profit as the only (or even most important) value. That led me to consider military shooters, where an authority figure gives a briefing, as implicitly supportive of bureaucratic, patriarchal systems. And a ton of similar things. It's not necessarily that I'm against all of that all the time (since I'm not really an extremist and I think there's a time and useful place for most things), but damn, I at least want to consider all the angles before I support one view or another; I at least want to be aware of what I'm saying (overtly or otherwise).

GS: Is there a boundary as a designer between stretching a game design to convey a specific message over considering its pure entertainment value?

HS: I agree with Marc Leblanc's model of games as pleasure. People enjoy games on many levels: Sensation, Fantasy, Narrative, Challenge, Fellowship, Discovery, Expression, Pastime. People sit and throw rocks into water and have fun. They whittle sticks, play Solitaire, chat with IM programs until 3AM, or try to spit on ants. (Admit it, you've done it.) People find a lot of stuff entertaining. Shakespeare is entertaining, even when the story is about death and betrayal. So, is there an inherent conflict between making something entertaining and conveying messages? Not for me. As Will Wright said when we were at Gallery1988, "That's the design challenge."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like