Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A hostile and vocal subset of gamers is threatening to boycott the game industry if it makes hardcore games more accessible to women. This article examines the numbers to see if this warning represents a serious danger to game sales.

The topic of institutionalized misogyny in game culture is finally getting the attention it deserves, and the situation is grim. Once again we embarrassed ourselves at the Electronic Entertainment Expo with a parade of booth babes and an Xbox One launch that featured a rape joke and not a single female protagonist among its launch titles. Try pointing this out to many industry executives and you’ll get a collective shrug. Try pointing it out in online gamer spaces and you get howls of outrage and a torrent of vile abuse from a small number of very angry men. The attacks get worse if the person who points it out happens to be a woman: death threats, threats of sexual violence, character assassination and cyberstalking are commonplace. Jennifer Hepler, a writer at BioWare, recently received explicit death threats... not to her but to her children, a new low.

The haters are simply infuriated at the suggestion that games might be improved by making them more appealing to women, and they’re warning us that they’ll do something about it. Apart from the abuse and threats, they say that they’ll stop buying games if the industry changes anything to make them more popular with women, and we’ll lose a lot of money. I decided to find out if we need to take this seriously, not just by arguing hypothetically, but by looking at some real numbers.

So who is asking for a change, and what exactly are they asking for? I’m going to call them “progressive gamers,” for want of a better term; they’re both men and women. With respect to gender in games (the treatment of racial minorities or under-represented sexualities is a separate, but related issue), their requests are simple and few:

More opportunities to play female protagonists in AAA titles.

More female characters—especially protagonists—who are not hypersexualized and whose clothing is appropriate for their activity.

More female characters portrayed as strong and competent people rather than victims, trophies, or sex objects.

Now let’s take a look at what they’re not asking for.

They’re not proposing to turn Duke Nukem female.

They’re not proposing to ban or censor Dead or Alive: Extreme Beach Volleyball.

They’re not proposing to kill off Princess Peach. (Well, most of them aren’t. There might be a radical wing that is.)

They’re not proposing that games should suddenly all be about traditional female role activities such as cooking and sewing. It shouldn’t even be necessary to say this, but there are a few dimwits around who seem to believe it.

In other words, progressive gamers are not trying to force designers to do anything. They’re asking for new games that they would find more enjoyable than the existing ones. It’s simple consumer activism, requesting products that better meet their wishes.

The players who oppose this, on the other hand—I’ll call them “reactionary gamers” because they want to keep things they way they are—are exclusively male. They say that they’ll boycott the game industry if it accedes to the requests of the progressive gamers. I’m both a progressive gamer and a game developer, so I have an interest in seeing more female-friendly games, but I also have an interest in making money, so I need to know if this threat amounts to anything.

Before I get into that, though, we’d better see if there really is a problem in the first place. Some people claim that there are plenty of female protagonists already, so there’s no need to do anything about it. But is this true?

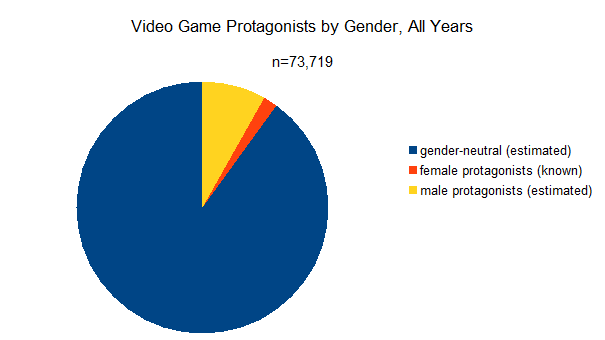

MobyGames is one of the largest databases of video games in the world. At the moment that I’m typing this, it contains records for 73,719 games. The data are entered by the community (with moderation from the site’s editors), and the site also includes the ability to add games to user-created groups of various sorts—effectively, a sort of tagging. The Protagonist: Female group documents games that only have female protagonists. Unfortunately, there is no group documenting games that only have male protagonists, so we’ll have to do some back-of-the-envelope calculations.

Let’s assume, very generously, that 90% of the games in MobyGames are gender-neutral. They either have no protagonist at all (e.g. Tetris), allow the player to choose between a female and male protagonist (Mass Effect), or allow the player to build a character from the ground up, including choosing its sex (Skyrim). I’m sure that’s an overestimate, but I’m giving the reactionaries the benefit of the doubt.

That leaves 7,372 games that have either a male-only (Max Payne) or a female-only (Mirror’s Edge) protagonist. Now, the number of games in the Protagonist: Female group at MobyGames stands at 1,327, which runs from the 1980 Apple II game KidVenture #1: Little Red Riding Hood to the 2013 version of Tomb Raider. In other words, only 18% of the total number of games with fixed protagonists have female ones. That looks like a problem.

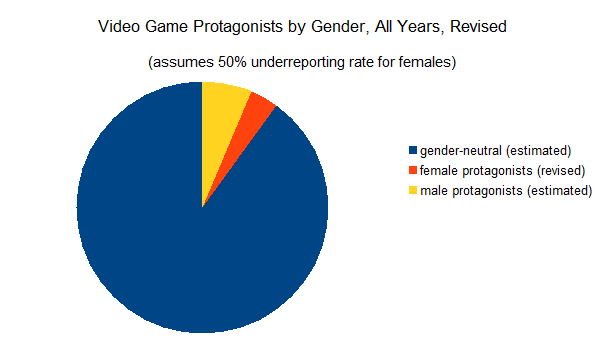

But the data comes from the player community, so it’s possible that the players haven’t put all the games with only female protagonists into the group. Let’s again be very generous and assume that the players have just documented half of them. This would mean that there are, in reality, 2,654 games with fixed female protagonists, or 36% of the total. 64% have fixed male protagonists. Still not good.

At this point someone is bound to argue that video games are aimed at men and so this imbalance is appropriate. But that’s not true; video games are not aimed exclusively at men and never have been from the very beginning: girls and women have played games from Pong onward. The game industry is not Playboy, despite occasionally resembling it. In any case, we know from the latest Electronic Software Association “Essential Facts” data sheet that the ratio of male to female players is 55% to 45%, not 64% to 36%.

In fact, I’m sure the discrepancy between the proportion of games with female avatars and the proportion of female players is much worse than that. I have bent over backwards to slant the numbers in favor of the “there’s no problem” viewpoint. So it’s pretty obvious that over the entire history of the game industry, games that offer a female protagonist are under-represented

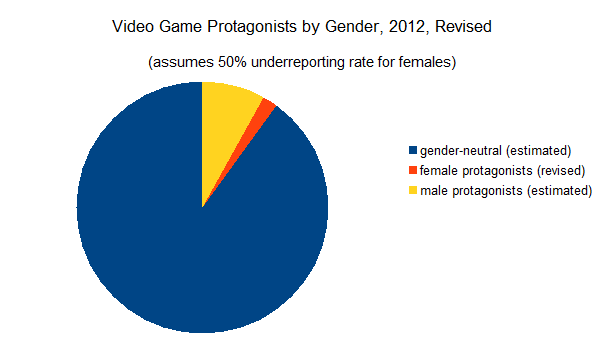

What about the current state of affairs? Again using data from MobyGames, in 2012, the industry made 1,749 games. Ruling out 90% of them as gender-neutral as I did before, that leaves 175 games with fixed-sex protagonists. The number of 2012 games listed in the Protagonist: Female group is 17, or 10%. Doubling this to account for any female-only protagonist games that got missed, we have 34 games or 19.5%.

In other words, the discrepancy between the proportion of female players and the proportion of fixed female protagonists is greater now than it has been over the whole history of the industry. If anything, we’re going backwards—from 36% over all to 19.5% in 2012. Yes, there’s a problem.

The reactionaries will also undoubtedly argue that there are lots of games that are gender-neutral, and women can just play those. (This is that 90% group that I hypothesized.) There are plenty of RPGs in which you create your own character, male or female; isn’t that enough? Or Bejeweled. No protagonist at all in puzzle games, so no problem, right?

No, and here’s why. Interactive storytelling is hard enough to do well when the player can influence the plot (which is why many games still tell linear stories), but it’s extremely hard to do well when the designer knows nothing about the protagonist, including its sex. This is why adventure games, in which story is paramount, almost always have a predefined protagonist. The stories in games with a predefined protagonist (such as the Silent Hill series) are generally better than those in games with generic avatar. Telling female players that they have to be content with gender-neutral games consigns them to a second-class status in which they don’t get the best stories.

The next question is whether we should do anything about the problem. If you visit YouTube or the gamer message boards frequented by reactionary players, you encounter, again and again, the same set of arguments for not building any new games that the progressive players might like. I’ll summarize them here:

Dismissive: They’re only games; they’re not important, so it doesn’t matter if there aren’t many women or their portrayal of women is unrealistic.

Male chauvinist: Feminazis are pushing their way into the game industry with their political correctness, and they’re going to ruin games and (male) gaming culture.

Ignorant: Asking for female protagonists in games is a violation of game designers’ freedom of speech.

Misogynist: “Wherever there are happy men there will always be a woman there to ruin it.” That’s about the mildest quote I could find.

Financial: Male players don’t like to play female characters, and they like to see the women in games eroticized. The game industry will lose a lot of money if it stops catering to those men.

We can write off the first four arguments pretty quickly:

Dismissive: If the content of games doesn’t matter, why are you objecting to some new ones?

Male chauvinist: This is identical to the argument that people used to use to keep Jews out of the country club, and it deserves the same response. If gaming culture will be “ruined” by making it a little less hostile to female players, then what you value in gaming culture—bigotry and exclusion—is not worth preserving. Let the ruination commence.

Ignorant: Asking for female protagonists in games is an exercise of freedom of speech. Consumer activism is not censorship.

Misogynist: Please join a monastery where you can lead a completely happy, woman-free life.

That leaves us with the financial argument, which is the only one that deserves serious attention. Let’s assume for a moment that the game industry is ruled entirely by money, and that profits are our sole consideration. Does the game industry stand to lose a lot of money by alienating men who don’t want games to have strong female protagonists?

To start with, the games that the reactionary gamers say that they’ll stop buying are avatar-based action games, RPGs, and shooters. They aren’t talking about aerial-perspective strategy games or Farmville. I know this, because if you point out that the casual free-to-play sector is making money hand over fist with very few hypersexualized female characters in it, they’ll say that those aren’t “real games” and their players aren’t “real gamers,” so they don’t count. However, to the game industry, every dollar counts. A dollar is a dollar regardless of what kind of game it was spent on.

The web site VGChartz.com documents global retail sales figures for the entire game industry since its beginning. They aren’t perfectly accurate, but they’re a good way of establishing the relative values of different titles. When sorted by lifetime global unit sales, the first fifteen games on the list are all casual or gender-neutral games and don’t contain anything that would discourage female players (a few might complain about the damsel-in-distress motif of Super Mario Bros., but it’s hardly Scarlet Blade). The top 15 includes such titles as Tetris and Wii Fit. The first hardcore game on the list, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, is at #16, and the next one after that is Grand Theft Auto: Vice City at #23. Five of the Call of Duty games are all clustered between #30 and 35. Or to look at in relative terms, Nintendogs has sold twice as many units as Call of Duty: Black Ops, and Black Ops has reached the end of its shelf life, so it’s unlikely to improve on that.

It seems pretty clear that if hardcore male-protagonist-only games were to disappear entirely—which they won’t—it might be painful to particular companies, but it would not be a financial disaster for the game industry as a whole. And the VGChartz data doesn’t even include all the Facebook games, electronically-distributed games, and mobile games, the vast majority of which are not hardcore. Hardcore games are an even smaller segment of the market than the data suggest.

Why do hardcore games seem so much more important than they really are? Because they are hyped, and get press coverage, entirely out of proportion to their overall financial significance. The midnight releases, the wall-to-wall coverage in magazines, and all the rest of the PR machine serve to create an illusion that hardcore games are the industry. Those games are expensive to buy, and publishers have to spend a lot to persuade people to purchase them.

Farmville and Angry Birds, on the other hand, don’t need a massive PR machine. They use a more effective and far, far cheaper way of attracting gamers: social networking. Social networking is largely invisible because it’s person-to-person rather than broadcast, and there is no need for midnight releases of a free-to-play game.

But of course, hardcore games aren’t going to go away, nor do the progressive gamers want them to. In fact, what progressive gamers want is more hardcore games, just with more appealing female characters. This is an opportunity to grow the hardcore market, and bring new players into it.

This claim is central to the reactionary players’ argument. They say that not only the reactionaries themselves, but men in general, will abandon video gaming if presented with female avatars.

This is obviously false, as Lara Croft proved long, long ago. All the way back in 2000, Eidos estimated that as many as 25% of the players of Tomb Raider might be women—in other words, they figured at least 75% of their players were male! Now, Lara was designed to appeal to the male gaze, and there’s not very much that’s conventionally feminine about her—she’s doesn’t put men off by being sweet and demure. But that’s just the point: she’s a female character in a heroic role, which is exactly what the progressive players are asking for. She’s nobody’s trophy or victim.

Nor do female avatars have to have Lara’s physical proportions to be popular with men. We have only a handful of examples, but they include Samus Aran, Chell from the Portal series, Lightning from Final Fantasy XIII and American McGee’s Alice. None of these women are simply sex objects or outrageously dressed, so the claim that men won’t play as women unless the women are eroticized is pretty clearly false.

Recently, Marcis Liepa of the University of Gotland conducted a study of 91 male gamers over the age of 18 that addressed exactly this issue. She asked them, given the choice, whether they would play with male or female avatars and how often. She found that only 10% of men would play solely with male avatars. 46% play as a female character at least half the time, and 5% choose female characters all the time. This clearly refutes the assertion that male players don’t like to play as female characters.

Liepa also asked specifically about the progressives’ proposal: what male players’ reactions would be to the game industry producing more games with heroic female protagonists. 71% said it would be “good” or “very good.” The remainder had no opinion, and—here’s the kicker—not a single respondent said it would be “bad” or “very bad.”

Now, Liepa’s participants were all Swedish males, and the majority of them were young. It can certainly be argued that they don’t represent a complete sample of male gamers worldwide, or even in the West. It’s also possible that some of them said what they thought the interviewer wanted to hear rather their own true opinions. However, the reactionary gamers are not at all shy about sharing their feelings on this subject, so I have to assume that if there had been any in Liepa’s sample, they would have spoken up. Furthermore, none of Liepa’s 10% who only choose male avatars said that it would be bad if the industry produces more games with female protagonists. There’s no shortage of games that meet their preferences, as I showed above.

By this point it should be clear that if the reactionary players leave in a huff, it won’t do us any real harm. Like all extremists, they wildly overestimate the number of people who agree with them, and the sales that they represent are too small a fraction of the overall numbers to worry about. They are noisy and obnoxious, but financially irrelevant. We don’t need the haters.

The only companies in the industry that are at risk are ones whose business depends on selling games to these clowns. It’s kind of stupid to alienate a large audience in order to serve a small one, and as our markets continue to grow, they will end up in a strange, pathetic little niche like strip poker games.

I haven’t even addressed the upside of making more games with heroic female protagonists: more sales to women. This one is difficult to predict, but I’m pretty confident that the number of women who would buy the new games that the progressives want would be greater than the number of reactionaries who would refuse to buy them.

Our biggest problem isn’t the haters at all; it’s conservative game industry executives who believe—on the basis of precious little evidence—that AAA games with female protagonists don’t sell. This is a self-fulfilling prophecy; if you don’t give them any marketing because you don’t expect them to sell, they certainly won’t. Furthermore, it’s illogical to blame poor sales of games with female protagonists on the protagonist alone, while blaming poor sales of games with male protagonists on everything but that. I don’t have time to go into it now, but David Gaider developed this point at length in his brilliant 2013 GDC talk “Sex In Video Games,” which you can see here. Well-made games sell well regardless, as the better Tomb Raiders have shown.

If you want to make a game with a female protagonist and you need some inspiration, I’ve started a Facebook page called Heroic Women to Inspire Game Designers. I also have a categorized collection of the same women on Pinterest. Every time I hear of a particularly brave or adventurous woman (or group of women), I add her to the page with a link to her story on Wikipedia. You don’t need a Facebook or Pinterest account to view the content.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like