Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

For most of the time that I spent developing it, my Holmes Cryptic Cipher game was in the "almost done" phase.

"The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time." - Tom Cargill, Bell Labs

In my previous post (First time publisher, long time player) I discussed my background as a life-long game player and my career as a web programmer. Today I will begin to discuss how Holmes Cryptic Cipher came to be.

I guess it was around nine years ago. I had moved to a new country where I didn't know many people. This was OK, because I'm a naturally introverted person and I prefer to spend most of my time playing strategy games. I don't remember where the idea came from, but I got to thinking about codes. Specifically simple ciphers where letters are replaced with other letters.

QW ERT YUI OPUA SDQF GRRA WRO ERT

I knew Javascript and HTML pretty well, so I started messing around with a web page where you could swap letters in a puzzle to try to solve it. I built it with no libraries, probably no CSS, and two rows of clickable buttons where you could click an F in the top row followed by a J in the bottom row to swap the two letters in the puzzle. It looked ugly and I didn't think anyone else would want to play it. It was mainly an exercise and proof of concept for me. I promptly forgot about it for nine years.

Where did I leave that great idea?

Fast forward to January of this year (2015). With much more web programming under my belt but still no complete or published games, I attended my first ever Global Game Jam, dragging my neighbour Bill along. In the days leading up to the Jam, I started feeling inspired and suddenly remembered that puzzle game from so many years ago. I didn't have the code or that machine anymore, but I figured that with jQuery and some other things I've learned along the way it would be easy to recreate it and even improve on the original. At the Jam I showed my working prototype to Bill and he was impressed. I told him that I really wanted to make it into a mobile game, but I don't know how to develop mobile apps. My Java skills are extremely rusty and I had never written a line of Objective-C in my life. Bill told me there are systems out there which wrap web pages in app-stuff and that I should investigate this.

We ended up building a prototype of a completely different game in the Jam, but afterwards I looked into what Bill had spoken about, and found Cordova and its more popular sibling, PhoneGap. Cordova promised to be just what Bill had described: a relatively painless way for a web programmer to build native mobile apps. Equally importantly, Bill was happy to work on this with me. The Holmes project had begun.

You might think that going from a working prototype to a finished game isn't so difficult when we're talking about a simple cryptogram puzzle game. You don't need fancy art or level design and there aren't so many moving parts to build or break. Still, it took about a month of the two of us sitting evenings and weekends to figure out how Cordova works and how to fit our square peg web page into the round hole of mobile apps. Thankfully I was unemployed and Bill and I are both crazy enough to program for fun, so evenings and weekends it was.

Money was also an issue (see unemployed above). I didn't want Bill to put any money into my crazy idea, and I didn't want to spend too much when I was unemployed. You might think we wouldn't need to spend anything. And you'd be right. Unless we wanted to support Apple devices. Or Android devices. Considering these two platforms combined make up over 95% of mobile devices, we sort of wanted to support them. For Android there's the Google Developers program, which costs a one-time $25 lifetime fee. For Apple, there's a yearly $99 fee. You pay these fees for the priviledge of building and selling apps on their platforms. Without paying the fees, there's no way to push your product.

Anybody want an app?

This isn't a huge investment for a guy who's normally employed as a web programmer, but when you're unemployed and have no expectation of making your money back, it's not a trivial expense. The other challenge was that Apple made it virtually impossible to develop an Apple app without an Apple computer, something neither Bill nor I own. Luckily I have a very generous friend who bought himself a MacBook Air solely to show his wife that he supports her dream of eventually publishing her own mobile game. "Borrow it for as long as you want. I only turn it on once a week to make sure it still works," were, I believe, his exact words.

So now I had a partner. I had equipment. I had a platform. I had invested money. What could possibly go wrong?

I think I spent an entire day trying to wrap my stubborn head around this one, and it still bothers me. In standard old-fashioned web development, your basic unit of measure is the pixel. A pixel is an absolute, indivisible measurement, you believe. You build everything with sizes and locations set in pixels and that keeps it consistent across different machines and browsers. Then you ask the designer how big something is supposed to be and she responds in points and you bang your head against the desk.

Responsive design comes along and says you have to deal with lots of different browser sizes and resolutions, and that's fine. You can deal with that in many ways. But then along come retina displays and device-pixel-ratios and now there are half pixels and two-thirds pixels and even 13/5 pixels!

For example, the iPhone 5's display is really 1136 by 640 pixels, but because of a device-pixel-ratio of 2 on the iPhone 5, css treats the display as a measly 568 by 320 pixels. That's a tiny box to work with.

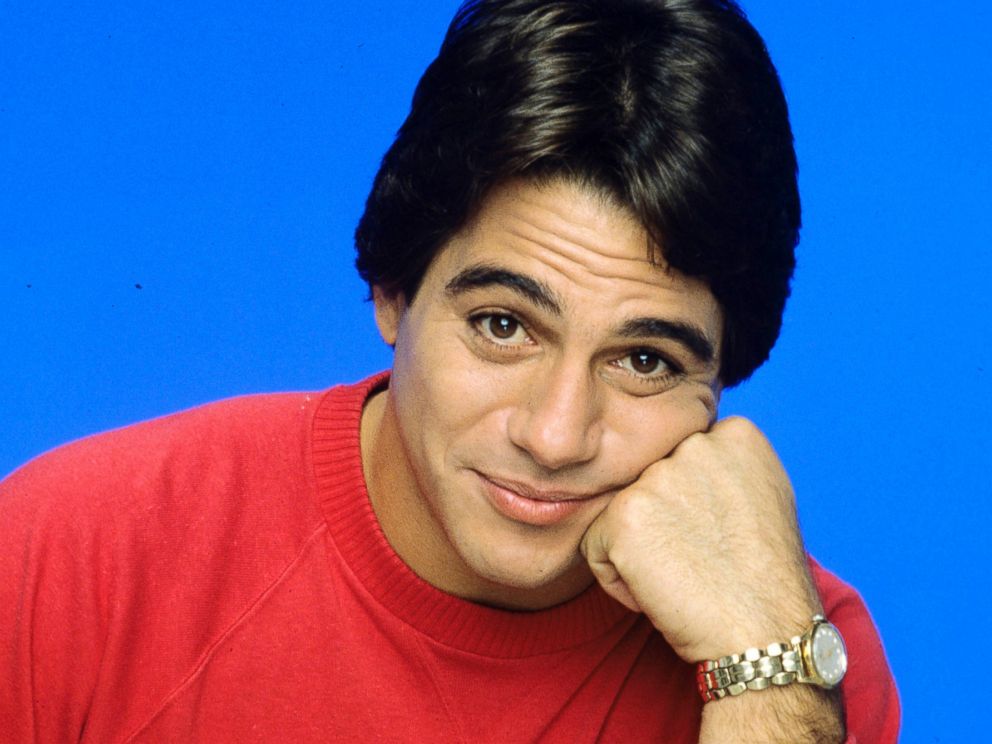

Even this Tiny Danza wouldn't fit in 568 by 320

What I wanted was a setting where you could specify "use real pixels in CSS styles instead of the double pixels" but no such setting was to be found. What ended up working well was forgetting pixels, and using ems to size and position just about everything. A few media queries for some targeted ranges of display size, plus some strategic font size choices (these in pixels) meant that I could use ems to get all the fake half pixels I needed.

Tune in next time when I discuss agonizing adventures in sound.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like