Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

As game designers, how do we encourage players to play better and longer in our games? One effective way is to design countermoves— emergent solution to specific problems.

A skill-oriented player in PvP games, when looking at a new game, would ask the following questions:

How do I play it?

How do I play it well?

How do I play it even better?

Players will start to learn the controls, and, in the meanwhile, try to figure out a strategy. That’s obvious. But what happens underneath the player’s consciousness? As game designers, how do we encourage players to play better and longer in our games? One effective way is to design countermoves— emergent solution to specific problems. In this post, I will talk about what they are, how they work and use card games as an example of how to design them.[1]

Before we define countermoves, the most important thing to look at is the control. When we say somebody is good at the control of a game, we mean that his or her input is precise and fast. Obviously, there are two ways you can challenge the players: make them unable to see correctly, or unable to act correctly.

Players “can’t see” because the game throws redundant and complex information in a short amount of time. They can solve this problem by:

Analysis

Relying on experience and memorizing levels

Muscle memory that triggers reflectively

Players “can’t act” when they know what to do, but just can’t do it correctly or quickly, because the game requires the player to input a series of commands consecutively, or be strict on the timing of their input. They can solve this problem by:

Familiarizing themselves with the hardware and control scheme

Focusing on fewer things

In trying to focus on fewer things, the players summarize and abstract their experience of trial and error, and compile multiple steps into one simple solution in their mind. Then they discover a countermove.

Countermoves provide players with the following advantages:

Faster reactions, because they shorten the overall time needed for multi-step control.

Greater chance of success, because they increase the chance that the players performed a right counter to a particular move.

Greater ability to multitask, because they save the players the energy to do more.

Now that we know where countermoves came from, and how players can use them, we can design them for the players to discover.

What’s the difference between a strategy and a countermove?

Players form a strategy when they put game elements together according to the rules of the game to gain a larger advantage or to find an optimal solution to the whole game.

On the other hand, countermoves are optimal solutions under particular, specific situations. They are the adjustment or backup plan when trying to play according to a strategy.

In short, we think about strategies before the game, and about countermoves during the game.

Since countermoves are reflections under the dome of a strategy, usually, the more strategies a game has, the more countermoves there will be.

If strategies pair countermoves one-to-one, it doesn't encourage players to think about countermoves. It only forces them to memorize solutions. However, we would love our players to think about countermoves, instead of bragging about a solution they found.

Therefore, what we need is a design that allows multiple solutions to the same problem. This way, players will need to make decisions as they go, and can’t have a dominant solution in every case.

There is one genre of game that:

Has no dominant strategy.

In which the power of all choices is dynamically changing.

Is not transparent — some information is hidden.

Has multiple choices most of the time.

That particular genre is fighting games: Street Fighters, King of Fighters, etc.

Fighting games have enclosed strategy sets — the characters. The sets won’t intersect with each other since a player only controls one character at a time. And the depth of countermoves usually won’t go more than three layers because of the complexity of the design. It is a genre that simplifies strategy and empowers countermoves to the extreme.

Yomi — an abstraction of fighting games.

Because of such design, players invented the term “taku” — choices, to describe the meaningful countermoves that they can choose.

Because fighting games are so about countermoves, there is also a term that describes the movement of players when they have a lot of countermoves.

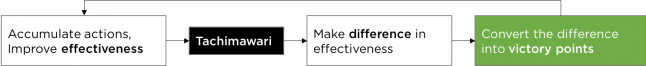

Tachimawari is the action that happens before an attack, or before the defense against an assault. The goal of these actions is to move into an advantageous position. In fighting games, players move back and forth before attacking, hence the name.

When you have enough countermoves, you will do everything you can to bring yourself an advantage in the next taku moment — that is Tachimawari.

A player may start from a tachimawari, find a way to score, then return to tachimawari again. Let us call it a “Tachimawari Cycle.” Every PvP game will have one or more systems where players will compete for scores — victory points.

The Tachimawari Cycle

Well-designed countermoves — ones that can create tachimawari — gives clear indications of the difference in skill level between two opponents. And a match between the same level would be a duel of mental strength.

So, how do we achieve this phenomenon achieved in other genres? Let us take a look at examples in trading/collective card games.

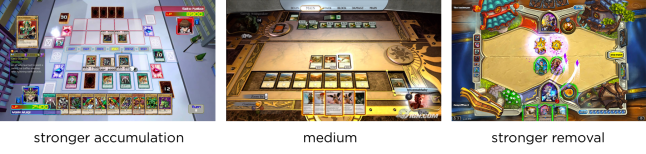

The card games that we often think of — Yu-gi-oh, Magic the Gathering, or Hearthstone — are unlike games of Rock–paper–scissors. They are not zero-sum games based on one element beating another. More often, they are “converting” games that provide resources, and judge players by who is the most efficient in converting the resources to victory points.

A large card pool and a big number of possible strategies.

Expanding card pool around existing core cards, creating extended strategies through iteration.

Many possible strategies.

Limited choices (taku) for efficient “conversions”.

(Number of cards in hand, cost, conditions to use the cards, etc. all creates limitations.)

You can see how card games to fighting games are different. Fighting games accomplish tachimawari through simplification of strategy. On the other hand, card games emphasize the competition in efficiency between strategies.

The winning elements in card games are:

Top decks

Choosing the deck according to current meta

Calculation and countermoves in a match

It is clear that countermoves are only a part of card games. Usually, card games utilize extra rules to make it seem that there are a lot of countermoves:

Side Decks allows the player to have supplementary cards that counter particular meta.

Limited Formats, such as Sealed Deck, forces players to change strategies between matches, thus bringing a dynamic to countermoves.

Optimizing the countermoves in a card game will make repetitive plays using the same deck more enjoyable, and thus boost the lifecycle of the card pool. You don’t want players to try out all the possible decks in three days and quit because the designer doesn’t have that many resources to keep throwing out new cards.

So, designing for countermoves in card games is adding complexity, in a cost-efficient way.

Let’s look at how to design countermoves following the framework that we established before: Allowing taku, allowing tachimawari, and forming the tachimawari cycle.

Three essential elements will enable taku:

Accumulating possible actions: As the game goes on, you accumulate cost, cards in hand, and permanents on the field. These are your possible actions.

Ways to keep these actions alive: Not allowing direct attack, separating attack and defense, dividing battlefields, or eliminating a threat from the opponent… these mechanics exist to protect the player from losing their accumulated actions too quickly. See the example of Infinity Wars below.

The battlefield is separated into Offense and Defense zones.

The defender chooses which cards to take damage.

There are costly spells to eliminate an enemy card directly.

The Balance between removal and accumulation: Or, how long do you want the player to keep their accumulated actions? If you have more ways to remove an opponent’s cards, then you are leaning towards stronger removal, and vice versa.

You can tell which side of the spectrum a game is leaning towards by counting how many cards survives on the battlefield throughout the match.

When you establish these elements, if you have a viable core mechanic to transform resource into victory, your game has taku in it.

Players need to be able to switch from a weaker taku to a stronger one. They don’t want to be stuck with little choices.

In an ideal world, we would want the attacker to have more but weaker takus, and the defender to have fewer but stronger ones so that they are willing to play aggressively. We can do this through:

Simple: the more the enemies, the stronger it is.

Cards that have dynamic power. They can be more powerful (valuable) according to some other elements on the field. A simple 4-cost removal becomes more powerful when there is a 10/10 enemy creature. A Flamestrike becomes more powerful when the opponent has more creatures on the field. There are so many ways to achieve this.

Dynamic power cards from Realm of Duels

Separating offense and defense. This is how Infinity Wars works. By distinguishing the offensive zone from the defensive zone, the game made it much easier to manage the balance. — But that’s a path that few has taken. It goes against a player’s intuition, and sometimes against the rule of simplicity.

In the real world, what we see often is one card that combines both offense and defense function. And that would require some tricks.

Killing tapped creature

If the game can distinguish offensive and defensive state, players will have more choices while defending. Magic the Gathering uses “tap” to do this. Whenever a creature attacks, it is “tapped.” And some cards kill a tapped creature.

If you can find a value that pivots the power of cards, you would be able to design cards that have a particular use for both offense and defense.

If you can give the disadvantaged player a stronger taku at match point, you would allow a dramatic comeback. Molten Giant is one of those cards.

It’s so easy to make a comeback that this got nerfed — use to be a 20-cost card.

If players don’t have enough way to obtain stronger takus, you would quickly end up with aggro decks dominating the game. The metagame then stagnates.

Now we have cards that would allow players go from weaker takus to stronger ones. But, why should they? What motivates the players to do tachimawari, rather than go for the optimal strategy and win easily?

There are ways that are unique to card games which will encourage players to think before they make decisions.

Response: in Magic the Gathering, you can cast an instant spell or activate an ability while another spell or ability is already cast or activated. Your response will take effect before the other one, creating risk for the offensive.

Hidden information: a card can be played face down. When there is secret information, one can never be sure if victory is at hand.

Error in prediction: Since card games don’t happen in real-time, players have the room to predict the opponent’s move. And they will make mistakes. A lot of times, the thought of “they might have this card” causes more loss than the opponent actually playing that card.

By involving risks, we can make it harder for players to predict the outcome of every move, thus preventing an optimal strategy and encouraging Tachimawari.

Let’s sum up what we talked about:

The basis of tachimawari in card games is the competition of efficiency in converting resource to victory.

In a cycle, a player accumulates actions, therefore have more choices (taku).

A player can go from disadvantage to advantage because of well-designed game rules and card power.

The game encourages a player to do tachimawari by involving hidden risk in offensive actions.

And we have the Tachimawari Cycle that’s specific to card games:

Card Game Tachimawari Cycle

Card Game Tachimawari Cycle

What do we see in card games? There are essential cards, countermove cards, and dynamic power cards. And there is the resource, the hidden information, and the victory point. What else can there be? Can there be multiple ways to convert resources into victory points — or even various kinds of victory points? Can some tools make any weak taku stronger? Can you establish a tachimawari cycle anytime at your wish?

There is still a lot more to explore in this genre and in other PvP genres, too. I hope this article answers the question of what is a countermove, why countermoves work, and how do they apply to popular PvP genres.

[1] This article is derived from research that I have done in cooperation with a handful of industry veterans. Special thanks to Jing Xie, my former colleague, and designer of Realm of Duels, for tutoring me about the basics of PvP gameplay and teaching me about the concepts and terms in fighting games. He provided the framework upon which this post takes form.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like