Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Consultant Christoph Kaindel takes a look at the real reasons and methods behind fights in history, offering up a few ideas for how everyday life in a late medieval city might be taken as inspiration for building believable game worlds for RPGs or sandbox-style action adventures.

June 21, 2012

Author: by Christoph Kaindel

[Consultant Christoph Kaindel takes a look at the real reasons and methods behind fights in history, offering up a few ideas for how everyday life in a late medieval city might be taken as inspiration for building believable game worlds for RPGs or sandbox-style action adventures.]

"In sandbox storytelling, the idea is to give the player a big open world populated with opportunities for interesting interactions. The player isn't constrained to a rail-like linear plot, but can interact with the world in any order that he chooses. If the world is constructed correctly, a story-like experience should emerge."

This quote from a column by Ernest Adams sums up a concept that might be the next step in the evolution of open world adventure games and role playing games. To make sandbox storytelling work, Adams suggests a combination of player-dependent and player-independent events. In other words, things should keep moving and changing in the game world without the player's intervention, as long as they are not critically important for the plot.

As a player, I immensely enjoy playing open world games. I love the sense of freedom, of discovery, of unexpected things happening; as a historian, however, I can't help comparing game worlds to real societies. Even though I realize that game worlds need to be simplified, I feel that many games could benefit from a little extra complexity, inspired by the structure of real societies.

Here are a few ideas how everyday life in a late medieval city might be taken as inspiration for building believable game worlds for RPGs or sandbox-style action adventures. As my main research subject was everyday violence in the middle ages, I will focus on that: the fight for fame and honor, following strict unwritten rules -- and in most cases non-lethal.

The essence of violence in games has, in my opinion, not changed a lot since the days of Pac-Man and Space Invaders. In most games, "doing violence" can still be summed up as: "The guys over there are your enemies. Point your gun at them and kill them before they kill you." Game violence usually means combat among players or between players and AI-controlled opponents; in both cases, enemies are just obstacles to be removed in order to progress in the game.

This has very little to do with real world violence. In real life, people use violence for many different reasons, to reach many different goals, to fulfill many different needs. People are motivated by greed, by fear, by lust, by hate, by sheer boredom, and there are many ways of acting violently, most of which are not fit to be used in games. Still, I believe if game designers took a little more time to consider the many meanings and uses of real-world violence instead of just making killing more and more visually spectacular, game violence and its consequences might be shown in more varied and interesting ways.

Ironically, game advertisements as well as critics of excessive game violence place a lot of emphasis on the purportedly "realistic" depiction of violence in games. While on the purely visual level, this may hold true for some games, combat in the majority of games follows action movie conventions, and while medpacks and regenerating health allow for more aggressive play, neither, of course, is "realistic".

Player motivation in most games is quite simple. The player character often is a soldier just doing her duty fighting hordes of single-mindedly aggressive opponents. Therefore, violence in video games is usually lethal, as enemies need to be removed on the way to completion of a mission. They never retreat; they never surrender. Once a fight has started, the only possible outcome is usually death for either enemy or player character -- ending the game and forcing the player to load a recent save.

This is a pattern that works reasonably well in linear shooter games; after all, a soldier would not be expected to argue with enemy soldiers or alien abominations. But open world games strive to give the impression of a "living, breathing" environment that is close to the real world -- and in such a setting I expect to have a wider range of combat options.

Until a few decades ago -- in some places and societies even nowadays -- the fight for honor was a non-lethal way of dealing with an opponent. Even though it has fallen out of use in real life, I think it might be well suited as a model of game violence to be used at least in historical or fantasy settings.

As a historian, I have done several years' research on the topic of informal everyday violence in late medieval and early modern Europe -- in essence, tavern brawls and knife fights. This topic has only fairly recently been picked up by crime historians, since about 1995. The history of crime is not so much concerned with written law codices, but more with how society copes with crime: what is considered a crime, how the persecution of criminals is organized, what punishments are applied, who is punished -- and who is not.

The Middle Ages are generally seen as a rather violent period. A late medieval city was a dangerous place by modern European standards; it was, however, considered safe by its citizens, compared to the hazards of the roads and forests around it.

Authorities tried to ban, unsuccessfully, the wearing of weapons in crowded places like taverns, brothels, bathhouses, and churches, where fights broke out frequently, mostly on holidays and weekends. Though daggers were often used, fights rarely ended in the death of one of the fighters; in most cases only superficial wounds were inflicted. Demonstrating one's courage and willingness to fight was often enough to keep face.

Men usually fought in defense of their personal honor, defined as the ability to protect one's personal space, reputation, family, home, possessions, rights and privileges. Insults in public escalated to brawls or knife fights. The goal was not to kill, but only to publicly defeat the other person.

Violent defense of personal honor was a necessity; if a man allowed his honor to be damaged, nobody would do business with him anymore, and he would lose social status. Therefore, even high city officials and nobles engaged in public fights, though only with their equals.

The concept of honor defines a group and differentiates it from other groups. Modern research suggests that the fight for honor constituted a form of self-regulation in a society that had no police and relatively weak central authorities. So, ritualized fighting was a constructive rather than a destructive element of society. It was used to make a point, to send a signal to the opponent as well as the "audience"; it was part of the communicative repertoire of adult men of all levels of society.

Everyday conflicts in the Middle Ages usually followed an unwritten code of conduct. The sequence of escalation started with insulting the other person, grabbing their lapels, knocking off their hat (a status sign), shoving them to the ground and, finally, drawing the dagger and fighting with fists and knife. Movements probably tended to be big and theatrical; a brawl was as much a display of fighting prowess for the benefit of spectators/witnesses as it was a real fight. The escalation sequence could be broken by intervention of bystanders.

The law treated these honorable fights in public places rather leniently. If somebody was wounded, his adversary had to pay a fine according to the seriousness of the wound. If a fighter was killed, the killer was banished from the city for several years. Cowardly murdering a person from behind, on the other hand, was a capital crime, and the murderer was usually executed. Theft was considered dishonorable and therefore much worse than public violence, and punishment was stricter. Also, punishment was always harsher for strangers than for citizens.

There also were other, more regulated forms of public fighting: tournaments, fencing schools and exhibitions, stage fights, wrestling contests, judicial combat and, later, duels.

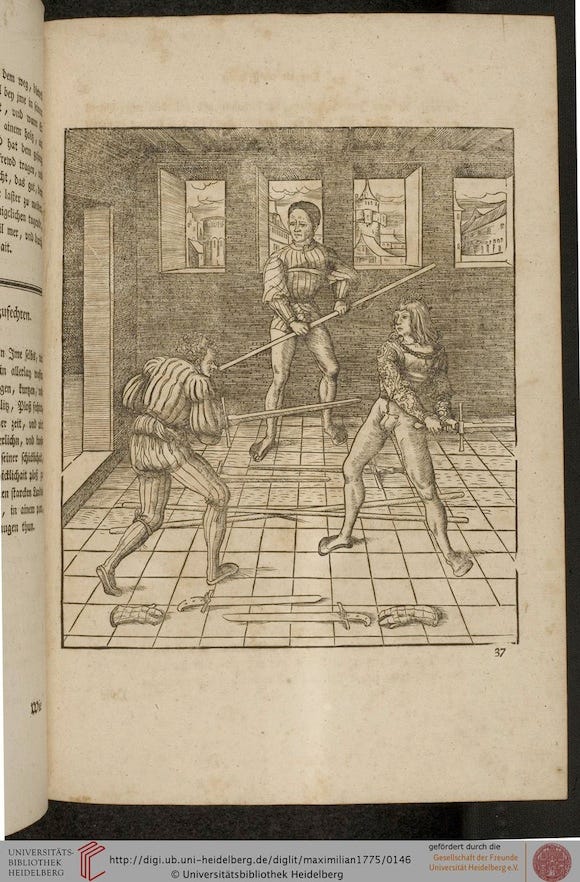

Illustration 1: Training with fencing swords. The trainer/referee in the background can use his staff to break up the fight. On the floor there are other training weapons -- note the “messers” in the foreground with their special protective gloves. Woodcut from Weiss-Kunig (written ca. 1514, printed 1775) pg. 92a. CC BY-NC-SA Heidelberg University Library

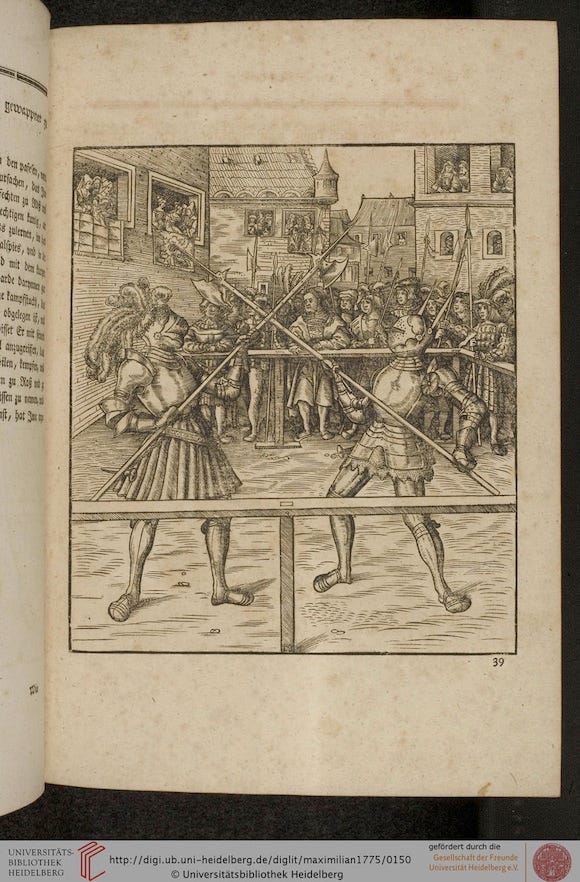

To tournaments, fencing schools, and wrestling contests the term "combat sports" might be applied, though they do not really fit the modern definition of "sport". From the 13th century onwards, tournaments were staged in cities, as only a city could provide accommodation for the hundreds of participants and their retinue. Tournaments were colorful spectacles. During the day there would be contests, jousts in several varieties, mounted group combat (mêlée) and foot combat, in the evenings banquets, dances and masquerades. Only rich knights, nobles and patricians could afford to participate in a tournament.

On the other hand, the fechtschule (fencing contest) allowed commoners to show their skill in handling swords, daggers, staffs and other weapons. They fought without protective equipment, but the most dangerous techniques -- thrusting, pommel strikes, throws -- were forbidden. A referee stood ready to interfere if illegal means were used.

Staged show fights were performed by professional Klopffechter, who were despised by fencing masters for their ineffective but flamboyant style aimed at pleasing the audience. They were the predecessors of the English prize fighters of the 17th and 18th centuries, who probably used a style of fencing that produced bloody, but only superficial wounds.

In the Middle Ages, wrestling was a popular pastime for peasants and nobles alike. Wrestling is the only medieval fighting system that has, as folk tradition, survived hardly changed until today. Austrian Ranggeln and Swiss Schwingen, for instance, are direct descendants of medieval wrestling.

Trial by combat was part of the judicial system for hundreds of years, falling out of use in the 14th century. The basic premise of judicial combat as an ordeal was that God would help the innocent to gain victory. Opponents were often allowed to hire a fencing master to prepare them for battle, or even a champion to fight in their stead. Commoners usually fought in close-fitting linen garments, knights and nobles in full armor. A judge would preside over the fight. Judicial combat might end in the death of one fighter, but nightfall, leaving the combat area or the judge's intervention could also end the fight.

The duel probably evolved out of the trial by combat. A formal duel required a challenge and the presence of several witnesses. Many duels of the 16th and 17th centuries, however, were nothing more than street fights. University students were notorious to duel at the slightest provocation; fencing lessons therefore were an important part of their studies -- as well as dancing lessons, and often taught by the same teacher, because the footwork was similar.

In all of these forms of combat, spectators were present; and so, the defense and advancement of personal honor and reputation played a major part, and the presence of spectators certainly had some influence on the way the fight was conducted.

Combat was different depending on the situation and on the weapons used. Wrestling was the basis of fencing and might be applied whenever the opportunity presented itself. Dagger fighting was quite close to wrestling; the fighting distance was the same, and daggers were often used as levers to enhance wrestling throws and locks. There was a big difference between fighting unarmored or in full armor; against the latter, sword blows had almost no effect, so armor-breaking weapons like maces or war hammers or a special sword fighting style called "half-swording" were used.

Though in modern European societies personal honor is usually defended in court, and public fighting has been officially relegated to the realm of sports, today's youth gangs and other violence-prone male groups still adhere to the concept of male honor described above, along with violent rituals.

Hooligans, for instance, take part in "tournaments" outside stadiums. The number of "competitors" on either side is the same. The fights are organized according to strict rules -- either with "equipment" or without it. And thus, hooligans are equipped with baseball bats, knives, axes, machetes, chains, etc. Often referees are present to assure that those who are down are taken out of the fight, and to decide which side has won. To win such a fight means to gain international prestige; there are online leaderboards for hooligans. That is why hooligan groups train beforehand and organize sparring fights.

So, to summarize: in violence-prone societies, fighting is a form of communication. Winning a fight increases personal honor and social status; by participating in a fight, and losing, honor may at least be preserved. In the following part I will propose a few ideas how non-lethal combat might be integrated in a medieval or fantasy game world. In a modern game world, the basic ideas could still be used.

Open world games featuring non-lethal combat

Game concepts close to the use of personal honor I described are the "style" rating of Saints Row 2 or the "fame" rating of Red Dead Redemption, though in the latter game this is supplemented by an "honor" rating to keep track of the player's good or evil deeds, similar to the "karma" of Fallout 3 and Infamous. But combat in these games is lethal; there is no way to win fame by just subduing an opponent.

There are only a few sandbox games I am aware of that use non-lethal violence as an element of gameplay, even though most fights may be of the deadly variety. The Deus Ex series is famous for allowing players to finish the games without killing anybody; but unconscious characters are still taken out of the game (they may be awakened by their comrades); violence, lethal or non-lethal, is only used to remove obstacles. I will focus on those games that also use violence as a form of communication, in the way I outlined above.

In 2006's The Godfather, the player character has to intimidate shopkeepers to make them pay protection money. Each shopkeeper has a certain weak spot that has to be discovered and then exploited in a kind of minigame, and of course shopkeepers should not be killed. So, the game's rather complex unarmed combat system has to be used carefully.

The intimidation missions bring some variety into a fairly standard third person shooter, and they fit appropriately into a game world of organized crime. Strangely, in Grand Theft Auto IV, a similar game in many ways, unarmed combat is also possible, but it is never really needed except in one or two missions. I found it fairly useless for most of the game.

Wrestling games don't exactly qualify as sandbox games, but I find them very interesting as a genre that combines non-lethal fighting with role playing elements. Contrary to many other role playing games, if you lose a fight in a wrestling game, the storyline continues, only in a different direction. Your position in the ranking list may change, but you will always stay in the game.

Professional wrestling itself has been compared to TV soap operas; both feature actors with clear-cut different personae interacting in changing constellations in a small number of locations. There are bigger and smaller interwoven storylines, often going on for several months or even years; driving forces are love and hate, loyalty and betrayal, courage and cowardice. Wrestling, however, is also presented as a morality play, as the big fight of Good against Evil. And finally, in wrestling, personal honor is all-important.

There is a strange paradox: professional wrestling is staged, but in wrestling games it is presented as a real combat sport. It is acknowledged, though, that audience approval makes a difference to the outcome of the fight. So, in contrast to other fighting games, in most wrestling games you not only have to overcome your opponent, but also win over the audience by performing flashy and varied techniques; only then will you be able to perform a finishing move. This is therefore the only type of action game in which the display of fighting skills is as important as the fight itself -- as it was in the ritualized fights in the Middle Ages.

In Rockstar's Bully (aka Canis Canem Edit) fights happen frequently but are entirely bloodless and non-lethal -- the fighting style is well adapted to the game world of a boarding school in a small American town. The player character -- Jimmy Hopkins, a rebellious teenager -- has to take on several gangs of bullies, but also fight in the boxing ring or in the school's wrestling team. The school is a violent place; often you will see weaker students bullied and pushed about by stronger ones. You can insult other students, but you can also get out of a conflict by apologizing or paying for being left alone -- this is the only game I know that has a violent escalation/de-escalation process.

If Jimmy is caught by an adult or loses a fight, he does not die but is just transported back to his room. As nobody ever dies, Jimmy will confront some people several times in different circumstances, which helps in getting to know them and developing relationships as well as conflicts. Defeating members of one faction will earn respect with their rivals. Several kinds of pranks can be performed, from pushing people into wastepaper baskets to throwing eggs and fireworks or breaking windows using a slingshot.

Bully is one of the few open world games that incorporates the passing of time into its narrative. The game day is structured around school lessons; if Jimmy is caught outside during a lesson, he will be forced to attend. There are also seasons: the game starts in autumn and continues through winter and spring. After the conclusion of the main storyline, in summer, you have the opportunity to finish all remaining side missions.

What I found most interesting in Bully were the restrictions imposed on the main character, all of them logical elements of the game world. The game world is a lot smaller than in one of the GTA games, reflecting the fact that a teenager's world is smaller than an adult's.

As a teenager, Jimmy is not allowed to drive cars. He has to attend class regularly. Though he will become a skillful fighter during the course of the game and will be able to beat all the other kids in the game, he still lives in a world ruled by grownups, who are invincible -- he can sometimes escape from their grasp, but he can not defeat them. All these elements -- the use of honor, non-lethal ritualized violence as a way of life, escalation of violent conflicts, the dominance and invulnerability of adults, and the passage of time -- in my opinion immensely increased the believability of Bully's game world.

Regular events and Procedural Mission Creation

Though open world games often have day-night cycles and are played for months of game time, no recurring events happen without the player's participation. I spent several days in the churches of Red Dead Redemption, but I did not witness a single Holy Mass. All societies are structured around rituals like these. For instance, regular events breaking the daily routine of medieval city life included church service, weekly market days, holidays and festivals with dances, races, sports and different kinds of contests. Other events happening at irregular intervals could be trade goods arriving at the harbor, bands of raiders plundering nearby villages, a visit by the local count, student riots, tax collection, the execution of a robber baron and so on.

If it were a game, similar to the Assassin's Creed world, the player might be given a choice to watch or to participate. All these events could instigate side missions or activities, and missing them should not be game-breaking. They will happen again later in the game, so the player will have another chance at, say, rescuing a robber baron.

In cities, crowded places would be dangerous, like taverns, brothels, guildhalls, or narrow bridges, but there would be little danger of dying in a fight. A player character might enter a tavern to pick a fight, or she might avoid them.

Dangerous places may also be a source of randomly generated side missions: a person asking the player for help against an opponent -- who might then hold a grudge against the player and return with friends a few days later. I am aware that Skyrim offers random side missions like these; but I do not know if they are all strictly one-shot or if they may have consequences later on.

Another way to make the game world feel more alive would be to give major NPCs a bit of freedom to follow goals of their own, similar to opposing factions in strategy games like the Total War series. The concept of honor could be a part of this. The basic premise for a game world using the concept of personal honor would be that in populated areas non-lethal combat is acceptable for player character and NPCs alike, but murder would be punished.

NPCs should have an honor rating that guides their actions; instead of just being decoration or quest givers, they should follow certain goals of their own, depending on variables defining their character. Though the game would have to contain agent-based simulation elements, it would not need to be a complex society sim, but provide interactions that allow interesting situations to emerge, like those unique "transgressive" play experiences Espen Aarseth describes [pdf link] that happened to him while playing The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. Of course, if a game is designed to produce these situations regularly, they do not constitute transgressive play anymore.

NPC stats might include Greedy, Belligerent, Forgiving, Popular, Alcoholic, Amourous, Hostile against X (insert other NPC) and so on. Getting into a fight should be one option NPCs have when interacting with each other, depending on their ratings -- imagine The Sims with daggers. Fights for honor among player characters and/or NPCs in front of an audience will usually be non-lethal and end in honor/status gain or loss with its consequences. The amount of honor gain/loss might depend on the number of spectators. That way, relationships between NPCs can change over time, conflicts may arise and be resolved, and the player/s may be involved or not. Strings of side missions could evolve out of these situations.

Personal honor and reputation as a driving force for player and NPC actions could lead to dynamically changing game goals, independent from the main storyline:

Short term goals: Actions and Interactions that demonstrate personal courage

Medium term goals: Appearance and possessions (clothes, house, horse/car, weapons)

Long term goals: Social position in the game world

It is common for players to strive for goals like these, but not for NPCs. Main quests would still have to be scripted, but could major NPCs be given "free rein" to follow their built-in ambitions? Would this add to the fun of the game, or would it make it unplayable? The unpredictable nature of the game would add to replayability, but probably also lead to difficulties trying to design such a mix between society sim, strategy game and action adventure.

Combat Sports, Duels and Show Fights

A simple application of non-lethal combat would be the introduction of different combat sports to the game world that would impose certain restrictions upon the player's fighting style, for instance by disallowing deadly techniques or limiting the use of armor and weapons. Strangely, this is rarely done in games. Many games feature some sort of arena combat, but most often, like in Oblivion or Borderlands (2009), this is just anything-goes and to the death.

Illustration 2: Armored foot combat with halberds, held in a wooden enclosure in a city square in front of a large audience. Woodcut from Weiss-Kunig (written ca. 1514, printed 1775) pg. 94a. CC BY-NC-SA Heidelberg University Library

I have tried to put the multitude of combat situations that occurred in the Medieval and Early Modern world in a simple roster. We could say there were eight distinct (though often overlapping, technique-wise) "fighting styles":

Equipment | Combat situation |

|---|---|

Non-lethal | Lethal |

Unarmed, not armored | Wrestling, boxing, brawling |

Armed, not armored | Klopffechten, theatrical fencing, Fechtschule, prize fighting, some duels, combat training |

Unarmed, armored | Tournament (subduing opponent after losing weapons) |

Armed, armored | Tournament |

The use of such a complex system probably would not be feasible in a game. But combat in tournament-like situations could be restricted to non-lethal means. Jousting, as far as I know, only appeared as a mini-game in 1987's Defender of the Crown and its remakes, and the somewhat similar Conqueror A.D. 1086. In these games you could win or lose honor, gold or land in the joust; important things were at stake, just not your life.

You might lose against a formidable opponent at first, but later you might be more skilled and defeat him. In that way, tournaments and other non-lethal combat forms can be used as motivation and to start a string of missions. For instance, the player character might witness a great tournament early on in the game, knowing that only many game hours later she, too, will be able to take part in such an event, and still later maybe able to win the big prize.

Other combat situations also could be easily adapted for use in games. The player character might be hired as champion for a trial by combat. Or she may be asked to instruct a clumsy noble, who has been challenged to a duel, in the art of fencing. Show fights, other than life-or-death combat, would require employing techniques that please the audience, a system similar to that used in wrestling games like the WWE Smackdown series. In a theater performance, the player character would have to fight convincingly without hurting their opponent. So, using in-game combat sports and show fights, the player would be forced to adapt her fighting style, adding variety to combat encounters.

Advantages of Non-Lethal Game Combat

Non-lethal fights, in the real world as well as in fictional worlds, have different meanings and impact than combat for life and death. In movies (and medieval epics) opponents that are defeated in single combat often become the hero's friends afterward -- never in games. In many movie westerns, there are barroom brawls, often used as comic relief, but there is the deadly duel at high noon as well. Both have a place in movies as well as computer games. Rockstar missed a great opportunity by neglecting the brawling mechanic in Red Dead Redemption. Yes, there is a trophy for winning brawls in all the saloons, but I would haveloved some missions that tested my brawling skills as well.

Non-lethal fighting might be used in the beginning of a game, to start things off slowly, as it is done in Assassin's Creed II. Later on, as conflicts deepen and things become more serious, combat may become lethal. This way, deadly violence, when it happens, has much more impact on the player.

Using non-lethal fighting in addition to lethal combat breaks up the strict dichotomy between safe zones and danger zones that exist in many games.

For instance, a fantasy (quasi-medieval) city would be reasonably safe: the player character might be involved in a brawl, but she will not be killed. A monastery would be completely safe, but the woods outside would be dangerous. This way, there would be shades of gray between completely safe and very dangerous areas, and the player would still know the danger she was in any time.

Dying and reloading or respawning always breaks game immersion. Losing a non-lethal fight, on the other hand, is an opportunity for some side quests: the player character may need to look for a doctor to patch her up; or visit a trainer to prepare her for the next fight; or just put in a training session by herself.

If the outcome and lethality of the fight depends on opponents, location and number and participation of bystanders, the player always has to decide what tactics and what weapons to use. An ambush by bandits would be a life or death affair, but it would not be allowed to kill a drunk assaulting the player character in a city tavern. If a fight happens, the player should often have a choice to participate or not; in some cases it might even be possible to end a fight in the escalation phase by bluffing.

The description of a little-known feature of Venetian popular culture may serve to illustrate my key arguments. For hundreds of years, starting with the second half of the 14th century and lasting until the early 1700s, the citizens of Venice regularly met in mock battles upon the larger bridges spanning the canals.

Fight between the inhabitants of the districts of Castello and San Nicolo on the Ponte dei Pugni (Bridge of the Fists). Note the sword fight among well-dressed spectators to the right. Venetian artist, 18th century. Copyright Fondazione Musei Civici Venezia, used with permission. (Click for large image)

At first those battagliole were fought with sharpened sticks; by 1600, they became unarmed brawls known as guerre di pugni, the wars of the fists. These fights that could vary in size between a few dozen to a thousand participants drew thousands of spectators who watched from rented balconies, gondolas or the roofs of nearby houses. The fights were dangerous; many fighters were severely wounded or even drowned in the canals. In 1574, 600 stick fighters gathered for a bridge battle in honor of the French king Henri III; after three hours of fierce fighting, the king is said to have exclaimed: "This is too small to be war, but too cruel to be a game!"

Venetian boxers were famed for their skill throughout Italy; but they were no professional warriors -- they were fishermen, craftsmen or shopkeepers. They took part because by fighting in the battagliole and rising through the ranks to be a capo, a leader, a simple worker could increase his social status in a way that would be impossible to achieve otherwise.

The guerre di pugni were regular combat events, fought mainly to increase personal honor. A game based on these bridge battles might be a brawler, an action adventure, a role playing game, or even a real time strategy game. It might even be transformed into a fantasy tale in which floating cities are connected by giant bridges that have to be conquered. Or it might just be an add-on to Assassin's Creed. I think Ezio Auditore would feel right at home in it.

Anglo, Sydney: The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. New Haven/London 2000

Aylward, J.D.: The English Master of Arms. London 1956

Barber, Richard; Barker, Juliet: Tournaments. Jousts, Chivalry and Pageants in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge 1989

Brown, Warren C.: Violence in Medieval Europe. London 2010

Davis, Robert C.: The War of the Fists. Popular Culture and Public Violence in Late Renaissance Venice. New York/Oxford 1994

Note: Some of these books are out of print, but may still be available as used copies. If you want to read just one, try Davis or Aylward. Great, and often surprising, reading.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like