Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra speaks with Alex Paterson, creator, director, writer, and artist on Not for Broadcast about the dev team's non-traditional background, making FMV games in 2020, and his approach to writing game scripts.

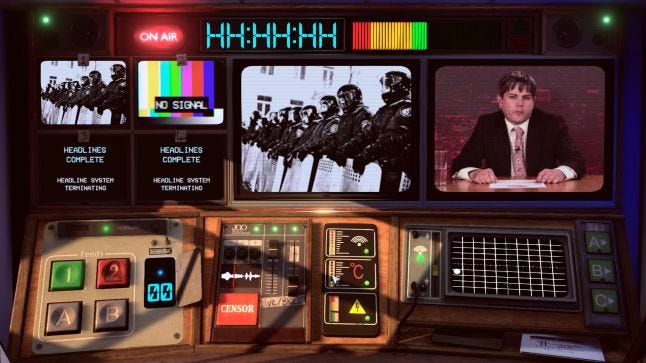

The ultra-niche "propaganda simulator" genre has a new entry with Steam Early Access game Not for Broadcast, the latest satire from Britain's NotGames.

Not for Broadcast puts the player in the role of a censor in charge a radical government's media operations, making "live" TV decisions about what to air and as the title suggests, what's not for broadcast.

We spoke with the game's creator, director, writer, and artist Alex Paterson about Not for Broadcast, who explained the non-traditional background of the dev team and how Sam Barlow's Her Story informed the game's design.

Who are you, and what is Not For Broadcast?

I'm Alex Paterson, creator, director, writer and artist of Not for Broadcast.

NotGames is a British game studio that opened its doors in 2013 to attempt to save the charity that brought us all together. Coming from a bizarre background of film, TV, theatre and comedy, NotGames aren't your usual game developers. If you're asking, we'd like to call ourselves 'multi-talented all-rounders', while our former employers would probably say we're 'unfocused and easily distracted.'

Not For Broadcast is an immersive, narrative-driven TV station sim set in an alternate 1980s as the nation stumbles towards dystopia.

An FMV game in 2020 is a rather bold choice. Why'd you do it? Would you say the play inspired by older FMV games like Dragon's Lair or Night Trap?

At NotGames we're not your usual game devs. We come from backgrounds in film, TV, theatre and comedy (it's actually how we all met) so film, comedy, and story were always going to take their place in the forefront of our games.

While I have fond memories of playing my uncle's copy of Tex Murphy adventure Under a Killing Moon as a child in the late 90s, I'd say as inspiration for NFB goes, we were much more influenced by Sam Barlow's Her Story and his innovative approach to FMV.

How much footage did you end up producing?

Hmm. Excellent question. Short answer: loads. We shot most scenes on four cameras simultaneously so that makes the total amount of footage just sky rocket. In Episode 1 alone, we've got over four hours of FMV. And that's only the stuff that made it into the game. One sequence, the Sportsboard Championship (super prestigious), is about an 11 minute sequence which we shot eight times.

Video production is not a skill in most game developers' toolbox. How'd you manage to create and maintain all those video clips? Do you have any tips for people making their own FMV games?

The honest answer is get people with the right skills. Our crew include directors, camera ops, booms, sound recordists, autocue operators, runners, make up artists, lighting, armorers, choreographers. And that's just the folks behind the cameras. We would not have been able to produce the content that we did without all of those people. Which is simultaneously what makes Not For Broadcast so interesting and unique and also just such a bad idea...

A tip for people making their own FMV games I'd say--don't feel limited to how other games have done it before you. We were adamant that our FMV wasn't going to be shot in the office with Gary from finance in a silly hat. Even though, on paper, shooting four-camera, 10 minute long sequences without any mistakes or cuts including music, dance and camera moves is a terrible idea, we meticulously worked out a way to make it work and then did it anyway.

The obvious comparison for Not For Broadcast is to Papers Please, which was released in 2013. Have you played it? How would you say NFB is differentiated from it?

Of course we've played it! It's similar in the sort of 'dystopian work simulator' angle but apart from that I'd say it differs quite heavily.

The main difference is of course the central mechanic of cutting together a live TV broadcast, censoring language and choosing ads. Lots of dystopias, including Papers, Please begin with their oppressive states already established. In NFB we wanted to explore ways these kinds of states can start and make people question the steps along the way almost more than the end result itself. We also try to leave the political morality quite open. There's no bad guys in our dystopia. The government certainly aren't evil. In Episode 1 they're actually fairly nice…

Although the point of the game is serious, a lot of the individual clips are comic. How did you balance the tone between the dystopian elements of the story and the humor?

We had our scripts read aloud as much as possible. We treat the writing process very much like writing a play (stick to what you know, right?), and gathered all the actors around a table to read the script. It's a sure fire way to judge the tone in a way that you never can while writing.

The atmosphere in the room does the job for you. The joke you're proudest of could get the least laughs or what you thought was a shocking revelation can fall flat. We'd then slink back to our keyboards and rewrite the script again.

The simulation element is interesting. Some parts (like switching feeds and playing ads) are similar to how a real station technician would work, while other parts (avoiding "interference") seem more fanciful. About what percent of the game is realistic? Did you feel like the play should simulate how someone would actually do this job, or did you make it more game-like as a nod to playability?

We always wanted to strike a balance between immersion and fun. We wanted the choices in the game to feel like they mattered, so it was important for the player to really feel in the shoes of the character.

But simultaneously it is a game and to make the mechanic as fun as possible we removed lots of the dull realism. We initially had a much more realistic sound desk with different mute buttons for different feeds but players found it way too overwhelming so we decided that, for now at least, giving too much control might actually negatively impact the experience of the game. People could accidentally mute the important bits and not know what they'd done for example.

And at a certain point if your goal is realism, the game stops becoming a game or a work simulator and just becomes work. Of course the player is actually taking on the jobs of many people in reality but by gamifying them down to their basic functions we managed to create that sense of one person having to constantly firefight and spin plates.

Playing multiple videos at once and quickly switching between them is something that's technically impressive even now, reminding me of demos for the old BeOS. Did you have technical trouble with playing multiple videos simultaneously? Any trouble with streaming bandwidth that you had to solve?

Yes! The biggest problem we had was getting videos to play ball across different platforms. Because of the way videos are decoded, it's not always simple to identify what the problem is, as you can't know what media packs or codecs a system has. We had issues where the game ran great on Windows 10 machines but just lagged unbearably on Windows 7 which turned out to be something solved by a Unity video hardware loading fix.

I personally have trouble with games with a plethora of controls, especially when they expect me to make quick decisions between many controls while under sensory assault. It's possible to make things arbitrarily difficult for a player in this way, by throwing them more balls to juggle. Where do you draw the line in terms of the number of plates the player is expected to keep spinning at once, so to speak?

Playtest, playtest, and playtest again. We regularly brought in fresh players and watched them play the game, watched carefully how quickly they learned the mechanics and what levels of multitasking were fun and what was too much.

Early on we actually overestimated how much the players actually wanted to do and discovered that just letting them focus on editing the show and paying attention to the FMV sequences was already pretty engaging alone. We found that as people mastered mechanics, it was good to slowly introduce more and the pacing is what actually mattered more than number of plates.

Once your ears are tuned to censoring it actually takes no time at all to slam the space bar when you hear an "F" or a "Geoff," but at the beginning, getting your brain around the concept takes a lot of your focus. So we've tried to keep that level of focus constant by forcing players to do new things at about an equal rate to them getting the hang of the old mechanics. It keeps the pressure and tension steady and stops you getting bored. Though of course every now and then it's important to ease up slightly and let the player feel cool for mastering something.

You May Also Like