Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This is it -- the whole kit and kaboodle. As 2016 shuffles off this mortal coil, Gamasutra staff reflect on the events, trends, games and -- most importantly -- the devs that shaped the year that was.

As 2016 draws to a close, it's been nice to look back over the year that was and reflect on what it meant for the art and business of game development.

Trying to pin down what the last twelve months meant for everyone involved would be a fool's errand, of course; the best we can do is hope that the year treated you well, and shine a light on some of the most notable events, trends and games that shaped the industry as a whole.

Gamasutra staff have been doing just that for the past few weeks, and today we draw that work together in a unified whole that aims to offer you a useful retrospective of the year that was.

Since the game industry is driven by developers, it seems only appropriate that we kick things off with a look back at the standout game makers of 2016. Below in alphabetical order are the 10 individual developers and studios, selected by Gamasutra's writers, that exceeded our expectations and pushed creative, commercial and cultural boundaries this year.

Last year, we praised Blizzard for surviving and thriving amid massive sea-changes in the industry, and 2016 only continues that trend for the company.

Last year, we praised Blizzard for surviving and thriving amid massive sea-changes in the industry, and 2016 only continues that trend for the company.

The rollout of Overwatch has so far been one of the company’s most successful commercial endeavors, launching the game industry giant into a new genre and successfully locking down most of the audience for the “hero shooter” genre.

But that’s not all the company’s been up to. After enduring a wave of criticism for the World of Warcraft expansion Warlords of Draenor, Blizzard made changes to its production model to successfully turn around its latest expansion Legion in a record amount of time, shortening the years-long gap between expansions to a single year. Given that Blizzard has been attempting this since the days of The Burning Crusade, the company’s ability to drastically respond to changing market forces needs to be commended, even when it’s in a genre they won long ago.

But lastly, Blizzard deserves extra praise for creating more diverse characters in its games and responding to the desires of its playerbase. While you could point to Overwatch’s diverse cast as proof enough of this effort, the fact that the company emphasized these values at The Game Awards this year stands as a shining example for representation the game industry, and how it can serve a global audience at the highest tiers of commercial success.

Eric Barone set out to create a game that was both an ode to Harvest Moon and also addressed some of the problems he found in the recent games of that series.

Instead, he ended up single-handedly developing something that breathed new life into a genre that had mostly been dominated by Harvest Moon since the '90s. Barone’s game, Stardew Valley, quickly found success after its launch earlier this year and managed to sell over a million copies in just two short months.

What makes Barone’s accomplishment with Stardew Valley especially notable is the fact that he developed the game entirely on his own. Every inch of the game - the code, art, story, music - was carefully crafted by Barone across Stardew Valley’s four-year development.

To accomplish this, he’s been operating in a state of pure crunch since announcing the project on Steam Greenlight in 2014. Before launch, Barone said he worked on Stardew Valley for 10 hours every day. Now that his game is out in the wild that number has jumped to 15 as he works on bringing Stardew Valley to more platforms and creating new features for the more than 1 million players that have fallen in love with his idyllic and captivating game.

One of the trends we observed in 2016 was how a few studios finally shipped games after a decade in development. Among these developers is D-Pad Studio, which deserves special praise for finally bringing the charming platformer Owlboy to the world.

Owlboy, in its creators’ own words, is a game that’s better judged by older games than the cutting edge of today, but the level of polish, craft, and interaction that’s present in this game would be considered stunning for any game studio. The fact that it was in the oven for 10 years, while some of its developers worked in flower shops and held down contract jobs? That’s nearly unthinkable.

It’s no accident that Owlboy’s story is about perseverance and pluck in the face of impossible odds—that it’s able to sell that story after surviving 10 years of gameplay is an astonishing and inspiring feat. Over the past decade, D-Pad exhibited something beyond the abstract idea of "passion" for a project; the studio showed a mastery of art and craft -- along with a heavy dose of commitment -- that is an inspiration to anyone working in a creative field.

First things first -- many teams at Sony pitched in to make the uniquely beautiful and affecting The Last Guardian over the course of its lengthy development cycle. But the finished product bears the unmistakable imprint of the people at GenDesign, a studio created by Fumito Ueda and some of the core team members who previously worked with him to create Ico and Shadow of the Colossus.

First things first -- many teams at Sony pitched in to make the uniquely beautiful and affecting The Last Guardian over the course of its lengthy development cycle. But the finished product bears the unmistakable imprint of the people at GenDesign, a studio created by Fumito Ueda and some of the core team members who previously worked with him to create Ico and Shadow of the Colossus.

Every single person who worked on making this ambitious game a reality should take immense pride in the result. But it’s the team at GenDesign who get our nod for creating a worthy successor to two of the most celebrated games in the history of the medium.

The Last Guardian is a continuation of the main theme of Ueda's previous games: exploring the bond between the player and a companion that they alternately rely upon and protect. This year, GenDesign inspired not only players, but also game developers, reminding once again that something as technical as game development can bring forth a work of art that reflects our innate, emotional tendencies as human beings.

Hello Games earned its place on this list for a couple of reasons. For one, No Man’s Sky was –

Hello Games earned its place on this list for a couple of reasons. For one, No Man’s Sky was –

and remains – an ambitious project, particularly for the small independent team at Hello Games, whose previous games were a couple of fun, arcade motocross affairs.

Procedural generation in video games has been a hot topic, particularly in the last few years, and we’ve seen great examples of it. But Hello Games took that concept and created an experience that will be remembered as an inflection point for procedural generation, showing how the technique can be used to create countless visually emotive, living worlds and inhabitants.

The other reason Hello makes it on our list is because of its perseverance in the face of adversity. As has been well-documented, the launch of No Man’s Sky was tumultuous to say the least. Hello Games and individuals within the studio have received online abuse and death threats, all of which, no matter your opinion on the game’s marketing, are inexcusable and indicative of some deep-seated problems in the relationship players have with developers.

Instead of letting these sizable challenges defeat it, Hello instead listened to legitimate criticisms, put its nose to the grindstone, and recently released the expansive “Foundation Update,” which, along with smaller, frequent updates, has since helped nudge the conversation around No Man’s Sky to be about actually playing and enjoying No Man’s Sky.

On one hand, Hello Games in 2016 was a terrifying case study of what could happen when a portion of a fanbase turns into a mob; the situation has really spooked some game developers, particularly small ones like Hello. On the other hand, Hello's year is inspiring, because if this small studio with big ambitions could at least begin to turn such a difficult situation around, then maybe other developers can persevere too.

In the beginning, there were video games. Many were good, and in their wake came countless sequels, spin-offs and franchises.

In the beginning, there were video games. Many were good, and in their wake came countless sequels, spin-offs and franchises.

Now, decades into the game industry’s lifespan, we’re knee-deep in remakes, remasters and reimaginings of older games, many of which fail to capture or improve upon what made the original work significant.

That’s not true of Doom, which id Software released this year to remarkable critical acclaim. Players, critics, and fellow developers praised the game (id’s first new release in half a decade) as a surprising return to form, one that breathed new life into the first-person shooter genre. It reminded us why the original Doom was so arresting, so influential, that for a time FPS games were known simply as “Doom clones.”

It’s no mean feat to create a genre-defining game. It’s arguably even harder to look back on such a work 20+ years later, accurately assess what makes it great, and use those elements as a foundation to build something new. This year id accomplished just that, and for that we recognize the studio as one our top developers of the year.

Hitman is the franchise that Copenhagen-based IO Interactive is known for. So messing with that winning formula is a risky endeavor.

Hitman is the franchise that Copenhagen-based IO Interactive is known for. So messing with that winning formula is a risky endeavor.

But sometimes change is required in order for even a popular series to remain viable. This year, IO announced that the next main installment in the Hitman franchise would be released episodically – one driving factor being the increased margins of purely digital releases when compared to disc-based traditional releases.

The decision had to be sold hard internally: shareholders, the development team, publishing teams, sales, marketing, and other parties all needed to be convinced. And then once that battle was won, an even bigger challenge awaited, as the fans had to be won over and convinced that this major shift wasn’t going to ruin their favorite franchise.

The transition wasn’t without its challenges. But the studio eventually learned how to effectively communicate a complicated business model to its audience, learned a greater understanding of accountability, and in the end created a new, market-proven variation of the episodic business model. That’s an accomplishment that may well reach beyond the walls of IO Interactive, and influence other studios that need to remain competitive – and maintain their existing fanbases – in an unforgiving market.

A popular game alone isn’t necessarily enough to land a developer on this list, but Niantic certainly deserves to be recognized for creating something that rapidly become a cultural phenomenon.

A popular game alone isn’t necessarily enough to land a developer on this list, but Niantic certainly deserves to be recognized for creating something that rapidly become a cultural phenomenon.

When the augmented reality game Pokemon Go launched this past summer, servers struggled to keep up with traffic that was nearly 50 times greater than the developer’s pre-launch predictions. Even so, the 70-person development team was able to weather the storm to create one of the stand-out social game experiences of recent time.

Niantic was able to create a game with this level of success by leveraging both the inherent popularity of the Pokemon brand and past experiences with their previous location-based game Ingress.

The gyms and Pokestops of Pokemon Go were largely built on crowdsourced landmark information provided by Ingress players since that game launched in 2012. It’s doubtful Pokemon Go would have done as well as it has without both the lessons learned and the resources Niantic gained through Ingress.

Pokemon Go could’ve easily been a one-and-done game that fizzled out shortly after launch, but the decisions made by Niantic in development, during launch, and following release ensured that it instead became a cultural icon that is as much a social experience as it is a video game.

As virtual reality continued to be one of the most talked about trends in 2016, Owlchemy Labs and its efforts in the VR space need to be recognized. This small studio out of Austin, Texas has proven to be a forerunner in the field of interactivity in VR, as exhibited by its game Job Simulator.

Don’t be fooled by its cartoony graphics and general absurdity: Job Simulator is absolutely the most intuitive room-scale VR game with the best affordance design on the market right now. That's all due to Owlchemy's world-class approach to design and development in a new generation of VR.

The studio is also keenly aware of the challenges facing the VR market, perhaps most notably the difficulty of showing people who aren’t in VR what it’s like to be in a VR game. Owlchemy recently showed off an advanced (i.e. mind-blowing) mixed reality method dubbed “depth-based realtime in-app mixed reality compositing.” Still in development, the fancily-named technique could have a huge impact on the effectiveness of VR marketing.

Owlchemy also seems to know that a rising tide lifts all boats, as the studio shares its own lessons learned, and is an active member within the VR development community. It's an important attitude to adopt, as VR is still a fledging space that needs to continuously advance if it’s to become more than just a flash in the pan.

Our own Katherine Cross praised Witching Hour Studios earlier this year for boldly stepping onto the world stage with a unique Singaporean style, but we wanted to celebrate the Southeast Asian developer for a variety of reasons. For one, its debut Masquerada: Songs and Shadows proved to be a thoughtful and engaging role-playing game that deftly mixed social issues with typical RPG design.

Our own Katherine Cross praised Witching Hour Studios earlier this year for boldly stepping onto the world stage with a unique Singaporean style, but we wanted to celebrate the Southeast Asian developer for a variety of reasons. For one, its debut Masquerada: Songs and Shadows proved to be a thoughtful and engaging role-playing game that deftly mixed social issues with typical RPG design.

For another, they’re the only developer on this list that had to go toe-to-toe with its own government to ensure it could bring a gay character to life in their game.

As we reported back in 2015, Witching Hour Studios first skirted the government’s laws about depictions of gay characters in media mostly via brief encounters at shared events. But as we discussed with creative director Ian Gregory, this evolved into a conversation with the government about the role media plays in Singaporean culture, and how gay characters should be depicted in games like Masquerada.

In the U.S., we recognize domestic game companies that understand the importance of workplace diversity (e.g. Electronic Arts was just named the most LGBTQ-friendly workplace in America). But it's also important to recognize the effort of a smaller studio overseas that's grappling with a humanitarian issue while shipping a noteworty RPG.

Click the link to page 2, and read our list of the top trends of 2016

Here, Gamasutra editor-in-chief Kris Graft takes a look at the trends that shaped the video game business in 2016.

It’s something that was a long time coming, but was still difficult to fathom: Nintendo, a company that on a fundamental basis is about creating hardware and software that complement one another seamlessly, was going to start making games for mass market, non-dedicated hardware.

First there was Miitomo – a slightly gamified (sorry) social app developed in a partnership with mobile game giant DeNA. It’s a fascinating, appropriately Nintendo-like approach to social interactions on phones. Although it was a flash in the pan when it launched this spring, it was a bright flash that hinted at the kind of audience Nintendo could draw on mobile devices. (Remember when we were all totally into Miitomo for those two days?)

Then came Pokemon Go's explosive success. While it was developed by Niantic (and remember, Nintendo only owns about a third of the Pokemon franchise), the Pokemon brand and Nintendo are inextricably linked. By mid-year, Nintendo was just starting to hint at the impact it may have once it put more significant resources into mobile.

Not actual gameplay.

And this week, we’ll be seeing what can be considered the first “real Nintendo game” on smartphones with the iPhone release of Super Mario Run. Directed by Nintendo stalwart Takashi Tezuka, the game is getting special attention from Apple, which seems determined to make it a success.

It’s a smart tack by Nintendo as it finally acknowledges that mobile games have wooed-away the mainstream audience once owned by the Wii and DS/3DS. Supplemented by the upcoming launch of the Switch console, Nintendo’s slow but sure move to mobile this year is laying the foundation for a potentially robust 2017. [Written just prior to Super Mario Run's launch.]

It’s true – last year we noted virtual reality in our top trends list, but the way the VR market has developed over the course of 2016 makes VR once again impossible to ignore, albeit in a different light.

Whereas 2015 was a year in which a select few had access to VR, 2016 was when VR became commercially available. Valve and HTC’s Vive is out, Oculus Rift hit shelves and recently added Touch controller support, and PlayStation VR had a strong launch with a more mainstream console crowd.

Maybe we'll leave this guy in 2016.

Maybe we'll leave this guy in 2016.

With these commercial launches, actual reality is beginning to sink in for VR developers. So far, what we’re seeing is that it’s difficult to make money on a VR game, which shouldn't be a surprise to people familiar with new markets with small addressable audiences. We’re also seeing developers try to mitigate the risk of getting into VR here in the early days, often by shoehorning existing games into VR (a practice that often doesn’t yield the best results). VR devs are also experiencing first-hand the difficulty in marketing and selling a game meant to be played while actually inside a digital realm. Those are just a few of VR's now very real challenges.

All of last year’s handwavey theories about the practicality, usability, and overall viability of VR games have been put to the test by the live consumer market over the last several months. Through all of the challenges, however, the VR dev community, along with platform holders, still seem extremely committed to the medium. That could be enough to make 2017 the year VR truly solidifies its position in game dev, if not a wider addressable market.

Game consoles have, once again, found themselves in an awkward position. They need to keep up with the times, but also simultaneously avoid wrecking the entire console game dev ecosystem by launching new proprietary hardware.

In 2016, Sony and Microsoft revealed exactly how they would attempt to navigate these tricky times, by announcing the PlayStation 4 Pro and the Scorpio, a souped-up version of the Xbox One. These new, more powerful iterations of their launch counterparts are meant to tackle higher-resolution 4K televisions, enable fancy HDR effects, improve framerates, and be ready for processor-intensive VR games.

More like late-life coolness.

More like late-life coolness.

Dedicated hardware continues to be the console market’s greatest strength, and also its Achilles’ heel. The fundamental question associated with the incremental-update trend is whether or not people will buy enough of these updated consoles to warrant console makers to continue such upgrades. The answer lies somewhere in the value proposition.

It’s also possible that more powerful consoles are a stop-gap as Sony and Microsoft continue to make moves toward video game and media strategies that no longer rely on dedicated hardware. We see Sony continuing to develop PlayStation Network, and making PlayStation play nice with PCs, and there’s Microsoft that’s increasingly integrating Xbox One and Windows 10. This isn’t to mention developments in cloud-based games, the logical goal of which is to use a network as the backbone for streaming and distribution on non-dedicated platforms like TVs and PCs.

I'm getting ahead of myself. In any case, for now we’ll humor PS4 and Xbox One, who’re snapping up that new Corvette convertible to let their graying temples blow in the breeze.

Part of making video games is getting money to make them. It’s not as sexy as the more creative aspects of game development, but typically essential for commercial endeavors.

This year a new kind of funding that’s been in the works for years finally went into wider practice in the U.S.: equity crowdfunding. Companies like Fig, Gambitious, and Indiegogo ramped up or introduced crowdfunding initiatives this year, with studios including ArtCraft (Crowfall), Double Fine (Psychonauts 2), Flying Wild Hog (Hard Reset Redux) turning to equity crowdfunding as a solution.

There're no good images of equity crowdfunding, so here is a watermarked stock photo of money bags.

There're no good images of equity crowdfunding, so here is a watermarked stock photo of money bags.

In case you’ve missed it, here’s what it is: In traditional, Kickstarter-style crowdfunding, backers pledge a certain amount of money, and project owners offer up rewards – like a copy of a game or a spot in the game’s credits – depending on how much money a backer contributes. Once a campaign hits its funding goal, pledgers’ cash is released to the team behind the project to go towards work.

Equity crowdfunding operates in a similar fashion, except instead of “backing” a project, backers become legally-bound investors in the project, potentially receiving an actual monetary return on investment. This style of crowdfunding is fraught with legal complications (equity crowdfunding rules in the U.S. were just finalized late last year), but the real investment aspect is appealing to people who might like to fund video game development and who wouldn’t mind making a bit of extra money.

While not as explosive as when Double Fine blew open Kickstarter’s doors for game devs in 2012, equity crowdfunding is a measured yet notable trend that more game developers may turn to as other funding options (like Kickstarter) dry up.

Last year, we noted the “indiepocalypse,” which was less of a real extinction event and more about fear and uncertainty as game markets matured and became increasingly crowded, competitive, and unforgiving.

2016 was the year that these fears and gut feelings began to creep into observable reality: As the quality bar rises on indie games, so do development costs; discoverability continues to be an issue as games flood the market; hits become bigger and fewer, squeezing out more indies; game devs have more and more in common with struggling artists and musicians; and so on.

Indies at the beginning of 2016 vs. indies at the end of 2016

Indies at the beginning of 2016 vs. indies at the end of 2016

While that sounds a bit depressing, at least there’s no mushroom cloud hanging in the sky just yet. The good news is that this year, there is less “omg the sky is falling on indie games,” and more “these are the problems – now that I can see them, I can try to solve them, or at least work around them.” Indie games might be headed for winter, but think about what your spring will look like.

Indies will need all the support they can get from platform holders as the new reality unfolds. Some have been more proactive than others – where Valve has continued to implement and address issues with its storefront (namely discoverability on Steam), others like Apple have done little to address the hurdles in front of small developers. Newer distribution platforms like itch.io also offer fertile ground for developers looking to avoid the worst degrees of noise.

While crowding markets are still a major concern, this year we see making a living as an indie is more complicated than just "fixing" discoverability. The road ahead is still difficult, full of potential pitfalls. But at least in 2016, the challenges became more apparent, and hopefully with that, so has a way forward.

Click the link to page 3, and read our list of the top event of 2016

Gamasutra editor Alex Wawro continues by looking back at some of the biggest events that shaped the industry in 2016.

Let’s start with a showstopper: Niantic and The Pokemon Company’s launch of Pokemon Go this summer.

We tend to shy away from calling out game launches among our top events of the year because they rarely have significant lasting influence on the game industry; Pokemon Go is an outlier, a free-to-play augmented-reality game that became a bit of a pop culture phenomenon.

Game industry execs sat up and took notice, to be sure, but Go's canny marriage of the broadly appealing Pokemon license with proven F2P AR mobile game tech got everyone from South Korean tourism officials to U.S. presidential candidates to the staff of an animal shelter in Muncie, Indiana talking about (and presumably, playing) the game.

A crowd of Pokemon Go players. Not pictured: the rest of this giant crowd of Pokemon Go players.

Before Pokemon Go, AR game design a relatively niche topic in the game industry; after Pokemon Go, it’s a pretty safe bet that AR games and experiences are being talked about in design meetings, conference halls and board rooms around the world. We expect to see significant investment and innovation in the AR game space in the years to come, and the lion's hare of that interest (if not all of it) is due to the high-profile success of Pokemon Go.

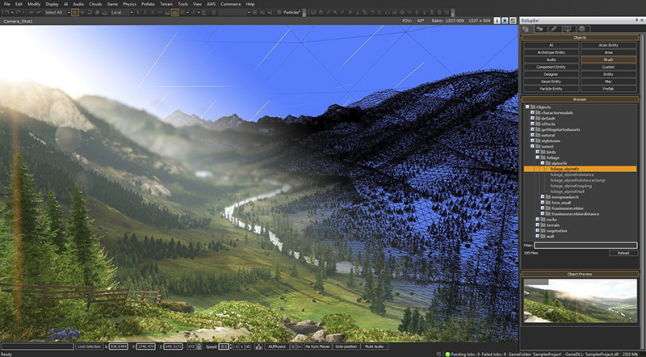

The game engine business in general was real interesting this year, but Amazon’s decision to field its own competitor against established players like Unity and Unreal was the event likely to have the biggest impact on the game industry in the years to come.

Amazon’s Lumberyard is a strong competitor out of the gate: built on CryEngine tech, it’s basically free for devs to use and capable of targeting a wide variety of platforms -- including VR. More importantly, it plays nice with Amazon’s extant tech: Amazon Web Services and Amazon’s Twitch.tv streaming platform, for example, which together support and entertain a significant portion of the Internet.

Acres of virtual lumber, rendered in Lumberyard.

That doesn’t mean it’s the best engine on the block, of course -- nobody but you knows what tools are right for the game you want to make. But Lumberyard’s remarkably robust debut this year has very quickly brought Amazon into the game engine market as a major player, and that’s likely to have a significant impact on the industry going forward.

Big, headline-grabbing hostile takeovers are notably rare in the game industry, so Vivendi’s successful conquest of Gameloft this summer was kind of a big deal. But beyond the takeover itself (which Gameloft's board warned was "likely to destabilize the company and its teams"), this is significant because it appears to be a major step in Vivendi's plan to re-enter the game industry in a big way.

Vivendi has had a hand in the industry for some time, of course, but it lost a lot of clout a few years back when it gave up ownership of Activision Blizzard. That decision proved pretty profitable for Vivendi, and the fact that it’s now invested some of its profits in wresting control of Gameloft is a big deal.

It also presages further shakeups in the industry, as Vivendi has made no secret of its plan to acquire both Gameloft and Ubisoft, uniting them under its banner. The fact that both companies were founded and run by members of the Guillemot family (though the family stepped away from Gameloft "with regret" following Vivendi's takeover) lends the whole affair another layer of human drama.

We don't know what the takeover looked like, so here's a stock photo.

In the face of Vivendi's encroachment, Ubisoft chief Yves Gillemot has publicly stressed how valuable he believes the company's "creative independence" to be and stated that a takeover "threatens the construction and pillars of Ubisoft." The company is one of the largest in the game industry, employing thousands of game makers around the world, and when you consider their fates along with all the Gameloft stakeholders who have had the course of their careers altered by Vivendi's takeover, it seems likely this acquisition has impacted the industry in ways we can't yet fully appreciate.

Disney surprised many of us this year by abruptly canning its Disney Infinity game franchise, effectively exiting the console game business.

This was a surprising and saddening move, since it meant the closure of Disney-owned Infinity developer Avalanche Software and the loss of roughly 300 jobs. It also spelled the end for a (seemingly popular and profitable) toys-to-life game franchise which had benefitted from Disney's collaboration with developers across the game industry, from Team Ninja to Sumo Digital to United Front Games (which itself closed down this year, months after Infinity was canned.)

Plus, this means Disney is now basically out of the business of making games. This isn't the first time we've seen Disney cut and run when it comes to game development -- the company has a history of killing game studios, including Junction Point, Propaganda Games and LucasArts -- but it does seem to be the last time we'll see Disney actively involved in anything other than licensing and mobile game publishing for the foreseeable future.

The end of Disney Infinity also spoke to a broader shift in the game industry away from toys-to-life games, which boomed in the wake of Activision's success with Skylanders but brought with them tricky concerns like shelf space and toy manufacturing costs. The market for games with physical toy accessories isn't doomed -- the Skylanders and Lego Dimensions games continue to appear on store shelves, and by all accounts Nintendo's Amiibo business is brisk -- but Disney's abrupt exit significantly shook some stakeholders' faith in toys-to-life.

Shelves full of Disney Infinity toys are a thing of the past.

Game industry analyst Joe Dodson told Gamasutra he was "shocked" by the decision, noting that he had been following the company because he believed it to be a leader of the toys-to-life market as a whole.

""We've been following the toys-to-life sector very closely, because the revenue growth since 2011 has been explosive. And Disney Infinity was a huge part of that growth. It was the market leader, it had ridiculously strong licenses," Dodson said earlier this year. "And in 2016 it's gone."

$8.6 billion. That's how much Chinese tech giant Tencent spent this year to buy a majority stake in Supercell, the Finnish mobile game company known best for F2P titans Clash of Clans and Clash Royale. Money is what powers the game industry, and when so much of it gets thrown around in a single deal we have to sit up and take notice.

Supercell's handful of hit mobile games have seen outsized success.

According to market analysis firm Newzoo, this deal immediately made Tencent the world leader (among publicly-traded companies, at least) in game revenues. Just behind it in the #2 spot is Activision Blizzard King, which rose to that position on the back of its $5.9 billion purchase of King in 2015.

The King acquisition was one of the biggest events of last year because it portended a shift in how major players in both the console and mobile game markets do business. This Supercell acquisition is likely to do the same, as it affords Tencent a commanding presence in a market it has struggled to penetrate: Western mobile games.

This may not affect most developers' day-to-day lives, as it seems like it would be in Tencent's best interest to allow Supercell to continue doing the work that made it so highly valued in the first place. But in the long run, this consolidates revenue in a way that's likely to shape how the game industry evolves. Tencent now controls the biggest revenue generators in both PC (League of Legends, operated by Tencent subisidiary Riot Games) and mobile (Supercell's Clash of Clans and Clash Royale) game markets. What will it do with all that money? We're about to find out.

Click the link to page 4, and read our list of the top games of 2016

Here then are Gamasutra's Top 10 Games of 2016.

Clash Royale is an imperfect game, but the concept is excellent. It's a light PVP RTS were action takes place primarily in two lanes. There are dozens of units to choose from, making up an 8-card deck, meaning combinations are myriad.

Clash Royale is an imperfect game, but the concept is excellent. It's a light PVP RTS were action takes place primarily in two lanes. There are dozens of units to choose from, making up an 8-card deck, meaning combinations are myriad.

At its best, the game is about precise placement of units to psyche out your opponent, turn your defense into a big push, and create new niches in the metagame for your deck to thrive in.

While it is a PVP game, and you can win or lose trophies during your daily battles (which is stressful), the clans are where I feel the game really shines. You can have a clan of up to 50 people, and there you can experiment with new deck combinations, trade cards with allies, and generally play around with strategies risk-free.

My clan consists of about one third Gamasutra and Insertcredit.com alumni, and two thirds some community from West Sumatra who found our clan somehow. It's great! Across language barriers, we all increase each others' skills.

Ultimately, a light PVP RTS is a great idea, and I personally enjoy using cards others don't, to make for a deck that surprises people when it works (three musketeers up in here). The free-to-play aspects of the game are pretty light, and the game can be played with minimal investment so long as you've got a clan to spend your time with. As long as new cards continue to keep the game fresh, I'll keep playing. (crying king emote). - Brandon Sheffield

Publisher: Bethesda Softworks

It was a long time coming, having gone through one major, unreleased iteration in Doom 4, but Doom 2016 delivered on what made the original so revered. It stands tall among today’s shooters, but retains the elements that make Doom, Doom. Fast, gory, precise, and overall super crunchy, Doom uses the franchise’s legacy as a strong inspiration rather than a template to blindly follow.

id Software identified the spirit of Doom, stuck to those core values throughout development, and conveyed that in an FPS that pays homage while feeling thoroughly modern. It’s the best-feeling shooter of the year. (Also: that Mick Gordon metal soundtrack, yeah.) - Kris Graft

Publisher/Funder: Panic

Firewatch is a game about two people talking in the woods, and I love it. It’s a great example of how a team can craft a game with vibrant, believable characters and meaningful choices without falling back on anointing the player as the savior/destroyer of the world.

Firewatch protagonist Henry is an unremarkable man with a bit of paunch and a bad few years under his belt; the game strikes a great balance, design-wise, between showing who Henry is (by fading in on him writing a letter, for example, or automatically annotating the map with his musings as the game progresses) and affording the player room to tell his story through dialogue choices.

The results of those choices are wonderfully delivered, too; nailing comedic timing and emotional subtext in voice acting is tricky business, but I think performers Rich Sommer (Henry) and Crissy Jones (Delilah) pulled it off beautifully here. The story of my time with Firewatch is utterly trite and totally true: whether you love or hate the ending, the best part is the journey. - Alex Wawro

Job Simulator on the Vive was one of my first experiences with VR, and honestly, I think it’s one of the best games to use to introduce someone to virtual reality. It offers a choice of jobs to experience - such as mechanic, chef, or office worker - and then guides players through completing comical approximations of tasks that represent each job.

For example, as the chef you might crack eggs to bake a cake and then add in a literal flower rather than flour to complete the dough. The little tasks through Job Simulator also give players a lot of freedom to just have fun doing really dumb things in VR.

There are a lot of neat VR games that let you explore dramatic stories and solve complicated puzzles, but sometimes you just want a game that lets you throw raw steak at your floating robot boss. - Alissa McAloon

Publisher: Sony Interactive Entertainment

The Last Guardian is so full of technical flaws, some of which could be attributed to a tumultuous, famously long development cycle, some of it due to choices made by Fumito Ueda. The camera is awful, the level design is incredibly unintuitive, your beastly companion Trico is unwieldy. So that leaves me to ask, why does this belong on my list?

The best answer I can come up with is that Ueda’s vision of companionship shined bright enough that The Last Guardian’s flaws didn’t matter much to me. Trico is the most emotive companion ever in a video game – even when uncooperative, it’s easy to just chalk that up to a streak of disobedience that any dog or cat owner is familiar with (classic “it’s not a bug, it’s a feature!” scenario).

Having a companion like Trico gives you motivation and reason to push through obstacles, both intentionally- and unintentionally-designed. No other game this year had an NPC that I cared about more than that stubborn cat-bird-dogasaur. - Kris Graft

Publisher: 2K Games

If you traveled back in time six months and told past-me that Mafia III would be one of my favorite games of the year, I’d have cheerfully A) asked after your wondrous time machine and B) said you were nuts.

Hangar 13’s debut game appears, on its surface, to be an unremarkable open-world game about gangsters, with little to set it apart from all the other open-world gangster games beyond a novel setting.

But what a setting it is! I lived in Louisiana for a time, and while the city we called home bore little resemblance to Mafia III’s simulacrum of late-’60s New Orleans, there are little details that feel right: the color of the light, for one, or the stark flatness of the landscape.

The game’s design also does a great job at conveying, through systems, some small piece of what I think it must feel like to be a mixed-race man living in the South. For example, there are two separate on-screen indicators that show the player where danger is -- one is a standard red reticle that appears during combat and spikes in different directions to indicate where enemies (and damage) are coming from, while the other is a blue reticle that shows the player where nearby police are and how strongly they’re looking at you.

In just about every other open-world game, that latter indicator would only appear when the player had committed a crime and was being hunted by police. In Mafia III, the police indicator is a constant -- it will always appear and show you that the police are watching you, even if you’ve done nothing wrong.

It’s a simple but effective system, one that serves a useful gameplay purpose (by informing the player when they should step carefully) while also fostering an oppressive feeling of judgment. - Alex Wawro

I paid zero attention to Overwatch before its launch, but it has dominated my free time since releasing earlier this year. The hero shooter is remarkably easy to pick up, thanks in no small part to a diverse cast of playable heroes. Currently, there are twenty-three characters to choose from, though Blizzard has been periodically adding to that roster since the game's release.

Overwatch quickly picked up a following in the competitive community but despite this, it still remains a game that can be enjoyed by players of different skill. With such a wide library of heroes to choose from, it's easy to find a character to start learning.

The game itself has a way of teaching players organically which characters work best in which situation, and there are no pay-to-win microtransactions built into the game. I admire Overwatch for its massive eSports presence, but I consider it one of my top ten games of this year for being a competitive game that is equally appealing to casual players. - Alissa McAloon

Publisher: Chucklefish Games

I’ve been playing fantasy farming simulators for well over half my life at this point and I still have no idea how they’re as fun as they are. For the longest time, the Harvest Moon series has all but dominated that genre, but somehow ConcernedApe (AKA Eric Barone) has beat Harvest Moon at its own game.

Barone’s game Stardew Valley captures nearly everything long-time fans love about the Harvest Moon series. Players start on an overgrown farm with nearly nothing, and are able to create a thriving farm through a little thing called resource management.

Planting the right crops and taking good care of animals is the simple way to explain the farming side of the game, but there’re a lot of deeper strategies involved. Players have gone as far as to set up elaborate spreadsheets detailing the exact profit per month generated by different types of crops. It’s honestly amazing.

Stardew Valley merges those basic farming mechanics with a crafting system and basic RPG-like leveling as well to create a game that players can easily dump hundreds of hours into. Personally, I’m sitting right around 140 and I’ve only played maybe four in-game years. - Alissa McAloon

Publisher: Electronic Arts

There’s often a steep contrast between military-themed shooters like Titanfall 2 and other shooters on this list like Overwatch or Doom. Where games like those emphasize playfulness or joy on the surface, military shooters—even science fiction-themed ones—take inspiration from military design to make heroic or dire moments, but lose something in raw playfulness.

Thankfully, that isn’t the case for Titanfall 2, one of many shooters that deserves to be celebrated in 2016 for featuring innovative design, but one in particular that deserves to be championed because it returns the joy of movement and velocity to a genre that’s adapted somberness.

It’s a game that constantly encourages the player to experiment with speed and carves individual levels and scenarios that have such a strong identity it almost feels like Valve’s classic Half-Life levels.

Across multiplayer and single-player (which shouldn’t even have existed, given how much Titanfall stretched itself thin trying to be a dedicated multiplayer game like Overwatch) Respawn has mixed a dash of charm and with a love of physics to create a game that fundamentally understands why shooters can still showcase top-notch design.

Plus it helps that BT-7274 is a REAL PAL. - Bryant Francis

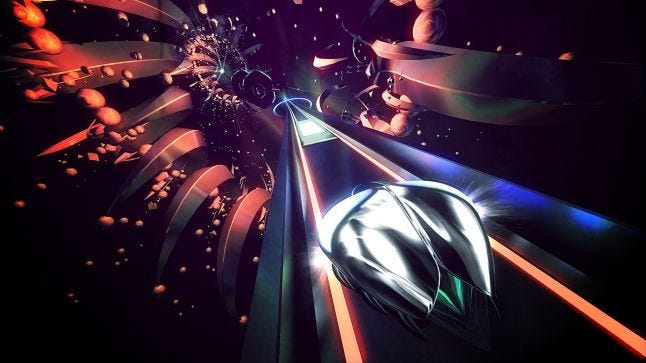

The marketing term used for Thumper has been “rhythm violence,” and it’s absolutely fitting. Thumper rewards precision visually and aurally, making you feel like you’re not just tapping buttons to a beat, but rather influencing the composition of the percussion-heavy music, at the same time destroying everything in your path.

When you play Thumper, you’re just pressing a button and combining that with a direction, at designated points on a track. That physical simplicity allows you to lose your senses to the game, as you’re shoved down the throat of a grotesque monster. Thumper is the perfect intersection audio-visual intensity; it’s synesthesia on a hard drive. - Kris Graft

Gamasutra contributors also each wrote up a personal top-ten list -- and you can read them here: Kris Graft, Alex Wawro, Bryant Francis, Katherine Cross, Chris Baker, Alissa McAloon, Chris Kerr, Phill Cameron, and Brandon Sheffield.

You May Also Like