Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"People of all ages, cultures and backgrounds enjoy being creative, so it seems only natural to make games which center that activity," says Greg Lobanov, director of Chicory: A Colorful Tale.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

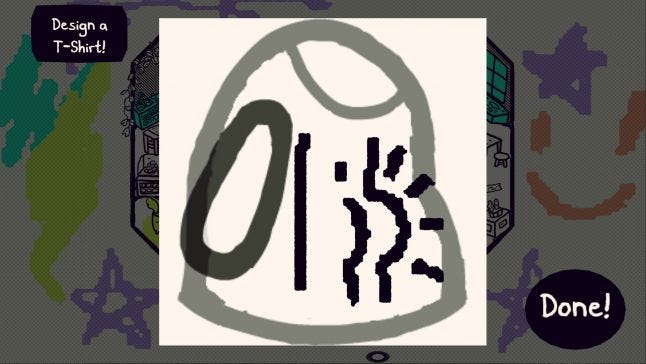

Independent Games Festival finalist Chicory: A Colorful Tale gives players a vast world of adorable characters and places to color as they see fit, asking them to let their creativity carry them forward as they explore it.

Greg Lobanov, director of the the Seumas McNally Grand Prize-nominated title, spoke with Gamasutra about what appealed to them about making a game that inspired creativity, that challenges of creating a world where players can alter all the colors, and how they tackled progression in this style of game.

I'm Greg Lobanov! I was the director, designer, programmer, and writer for Chicory. I grew up making paper card games and board games, and then freeware GameMaker games that I regularly posted online. I've always been making games, basically. It's as natural as breathing to me.

I wanted to make an adventure game where the player's main interaction with everything was drawing. I also wanted players to be in a creative headspace as much as possible, whereas a lot of other drawing games tend to fall into more problem-solving or resource-management type gameplay. I didn't really know if it was possible, but exploring in that direction got me to Chicory.

The game was primarily made in GameMaker Studio 2. I made a custom level editor and audio implementation tool to do fancy technical stuff. Characters were animated in Flash (by Alexis Dean-Jones), everything else drawn in Photoshop (by Madeline Berger and myself), audio was edited in Reaper (by Em Halberstadt and Preston Wright), and music was made in Ableton Live (by Lena Raine).

It took a surprisingly long time to figure out [laughs]. I knew the game would involve drawing and I eventually landed on the idea to make it black and white because it made drawing more fun if all the color in the world was made by the player. Once that was figured out, more and more cool ideas flowed and piled on top of each other. It's always a bit like that.

Honestly, the beginning of both projects was purely creative experimentation/speculation. I just wondered if it was possible. But the more I explore this space, the more I wonder why so few games seem to be exploring it. People of all ages, cultures and backgrounds enjoy being creative, so it seems only natural to make games which center that activity. It seems way more natural than, like, murdering goblins or managing factory simulations, anyway.

Clarity was a big challenge [laughs]. Usually color is a tool for communicating things to the player, but in this game the player can actively subvert the visuals and make things even harder to parse. So we went back to basics and thought a lot about silhouette and consistent visual language for things like collidable surfaces.

As far as encouraging the player to color it in...that wasn't too hard. Give people the tools and they will want to do it, because it's fun by its own merit. The artist who drew our environments, Madeline, is also a really gifted comics artist . I honestly think a lot of this game's visual success rests on the shoulders of Madeline's naturally charming art aesthetic.

Part of it is that we clearly partition the game between creative tasks vs. progression tasks. If the player has to be creative to make progress in the game, then the creativity is no fun anymore; it just becomes a means to an end. So, we were very careful about how things are presented to the player, and we also try to give space for players to explore whichever aspect is more appealing to them. Every player can enjoy doodling and making stuff with no direction, and every player can enjoy solving puzzles and reading story while their creative brain rests. How much of each they prefer is different by person, but always having the option to do either makes both more fun. There was also a lot of care put into the puzzle mechanics to make them feel more open and playful, so that even when a player is solving a puzzle it feels like they're playing with a toy.

Alexis Dean-Jones did the character designs; she was the first person to join the project and a huge reason why I even wanted to make it was because I wanted to create a world populated with her amazing characters [laughs]. Alexis put a ton of attention into giving every character a unique shape and feeling. Between the design, the species of animal, and their food-based name, players can get a REALLY strong first impression from a character that we can then build on or subvert with their dialogue. From the game design side, I also supplied a lot of starting point ideas for fun interactions and sidequests, so almost every character has a gameplay purpose or something fun to do. Nobody is just there to fill space.

Honestly it's because we like playing games co-op and it's something we would have wished for if we were playing this game ourselves. The way players engage with it is pretty open-ended. There's nothing too fancy to it. It's really just nice to solve puzzles with a second set of eyes and to have something to do together. Like sitting across from a friend over a big sheet of paper with colored markers.

This game, an IGF 2021 honoree, is featured as part of the Independent Games Festival ceremony. You can watch the ceremony starting at 4:30PM PT (7:30 ET) Wednesday, July 21 at GDC 2021.

You May Also Like