Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

I worked with Brookhaven National Laboratory and the New York Historical Society to recreate one of the first videogames ever made: 1958's Tennis For Two. Here's what I learned by recreating a game designed half a century ago.

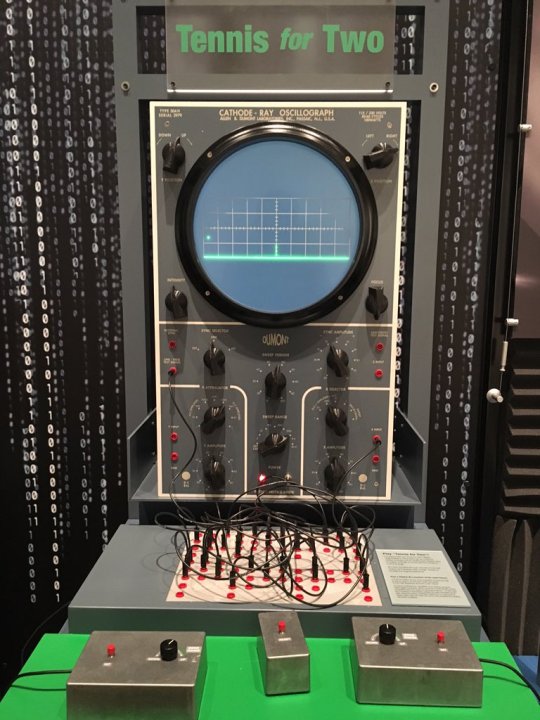

One of the most fun projects I had the opportunity to work on this year was a recreation of the 1958 videogame Tennis For Two, which is fully playable and installed in the New York Historical Society as part of their “Silicon City” exhibition. Since the exhibit opened to the public two weeks ago (the first time Tennis For Two has been publicly playable for longer than a few hours!), I’ve gotten a lot of questions about Tennis For Two and how the project came together.

In early 2015, Jeanne Angel, Media Producer for Exhibits & Special Projects at the New York Historical Society, got in touch with my game studio, Dozen Eyes, about Silicon City, a planned exhibition about the early history of computers in New York City and the surrounding area. We ended up making several interactives for Silicon City (one of them, a projection housed in a giant geodesic dome featuring mid-century collaborations between New York performance artists and computer scientists is a must-see for anyone interested in modern “new media” venues like Babycastles or Eyebeam), but the most exciting piece was a recreation of 1958′s Tennis For Two.

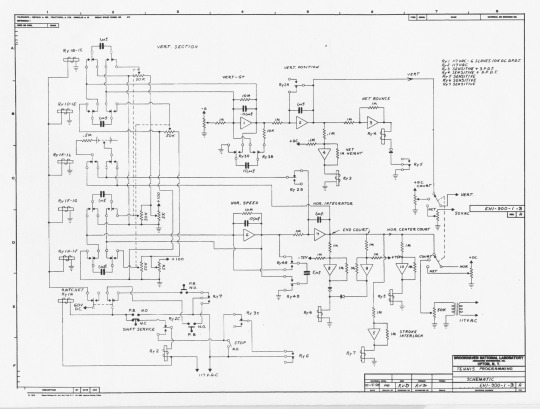

William Higinbotham built Tennis For Two for Brookhaven National Laboratory’s 1958 Visitor’s Day. Higinbotham wanted to showcase the latest developments in computing. One of the lab’s analog computers was able to compute trajectories for ballistic missiles. Using this as a foundation, Higinbotham drew up the program diagram for Tennis For Two in a couple of hours, and spent two or three weeks building and debugging with Robert V. Dvorak (even in 1958 videogames were associated with their designer, and not their programmer). While much of the game’s state is controlled by resistors, capacitors and relays, the real-time simulation of the ball, as rendered by an oscilloscope, required blazing-fast 2N140 Germanium-alloy transistors (developed by RCA in 1957). If Tennis For Two is not the very first videogame, it is almost certainly the first videogame intended to showcase bleeding edge graphics technology.

Hundreds of people lined up to play Tennis For Two on Visitor’s Day in 1958. So many that Brookhaven showed it again in 1959. After that the machine was apparently cannibalized for parts.

In May, Jeanne arranged a trip out to Brookhaven National Laboratory. BNL consists of rolling grassy fields punctuated by buildings in wildly differing architectural styles (it remains a popular shooting location for period tv shows), and it is the sort of place where the nice man in the polo shirt that you met on the way to lunch is actually one of the top physics minds on Earth. Despite all the cutting edge research and technology at BNL, it still feels like something out of a different era, or an alternate universe. The cafeteria feels less like Google than a small liberal-arts college. Nobody looks like a 20-something brogrammer. Few people look under 30. Everybody has a government job and a pension. All the people I talked to had worked there for at least 20 years. Perhaps there’s some egalitarianism left in tech after all.

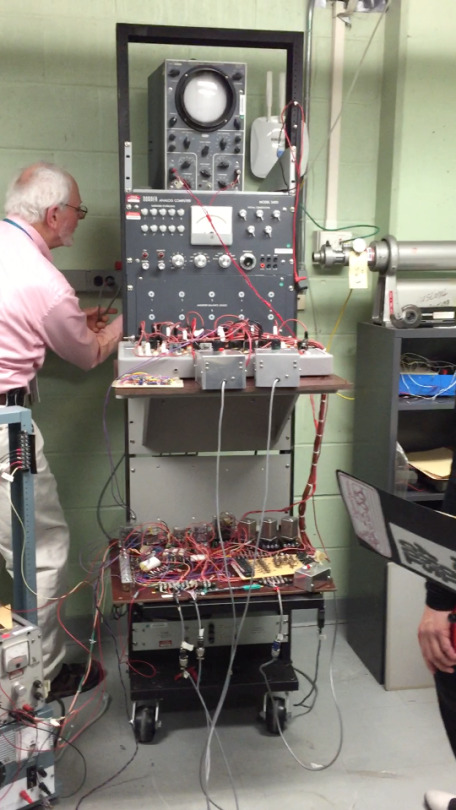

At Brookhaven, we met with Peter Takacs, a physicist who as part of the lab’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1997 helped rebuild Tennis for Two from Higinbotham’s original schematics using vintage parts (vacuum tube-powered Donner analog computer, and all). Peter took us to a small storage room deep in the bowels of a literal Cold War bunker where the game was kept, and after playing with a few connections, managed to get it up and running for us to play.

The actual machine is a pretty amazing thing, with relays that make a loud physical CLACK every time a button is pressed, updating the game’s state. There’s a subtle electrical hum in the air, joined about 30 minutes later by a faint burning smell. A 2010 attempt at installing Peter’s build in the Museum of the Moving Image showed that, unfortunately, it was far too fragile to be publicly playable for more than a couple of hours.

(Relatedly, Peter mentioned an anecdote I hadn’t heard before, which is that on Visitor’s Day in 1958, Tennis for Two was so popular that components burned out while it was running, and electrical engineers had to stand by to quickly swap in fresh components in order to meet the demands of the public. This aspect of the 1958 machine is not replicated at NYHS, which was made with Unity and runs on a Mac mini with a 4k monitor at full resolution)

If you look up Tennis For Two online, you’ll quickly learn that Higinbotham’s schematics contain a couple of errors. We know that Higinbotham and Dvorak must have found and corrected these bugs, but they never bothered to write down what their fixes were. It’s a reminder that videogames have always had a difficult relationship with conservation. Recreating the actual plans would result in nothing, so we have to improvise our own solutions in order to recreate what we know about the experience as best we can.

Tennis For Two has two controllers (ours were made by Adelle Lin and are powered by Arduinos), consisting of a dial for setting the angle of a hit, and “Hit” button. A separate button resets the ball to the service position of the last player to score.

Not that the game keeps score.

Having watched people play Tennis For Two, I’ve noticed two phases that players seem to go through. First, players used to modern videogames are surprised at how Tennis For Two subverts their expectations. For one thing, the game has no notion of score, or how long a match should be. The effect of this calls to mind modern mobile games like Super Hexagon or Downwell, where as soon as the immediate game ends, the player is only one button push away from an instant rematch. Players will zone out for 15-20 minutes going back and forth, perhaps only stopping when somebody taps them on the shoulder.

Most players also quickly figure out that any time you press the Hit button, you hit the ball. It’s impossible to miss, and the ball’s speed is slow enough that you nearly always have time to react. This causes many players to ask if Tennis For Two is “even a game,” since we’re used to thinking of tennis videogames as being like Pong, where the whole point is to “AVOID MISSING BALL FOR HIGH SCORE”, but then a funny thing happens: somebody spikes the ball downward.

One of the few rules Tennis For Two enforces is that you can only hit the ball one time after it enters your half of the court. This means that a hit that fails to put the ball over the net will lose you the point, and the easiest way to force your opponent to do this is to get them to hit the net by volleying the ball back and forth, and then spiking it downward before they can adjust. Spikes can be defended against by waiting for the ball to bounce back up, but the timing of that wait can be subverted by a strong horizontal slam, which is itself vulnerable to a spike.

Players who figure this out discover that Tennis For Two is actually a reflex bluffing game, similar to Street Fighter II, where competitive play is about building momentum and forcing your opponent to make an error you can exploit. As a game developer, it’s fun to watch players pick up the controllers and twist their mouths as they wonder whether this “game” is just some glorified mid-century tech demo, only to see their faces light up when they discover the real game hidden behind the word “tennis.”

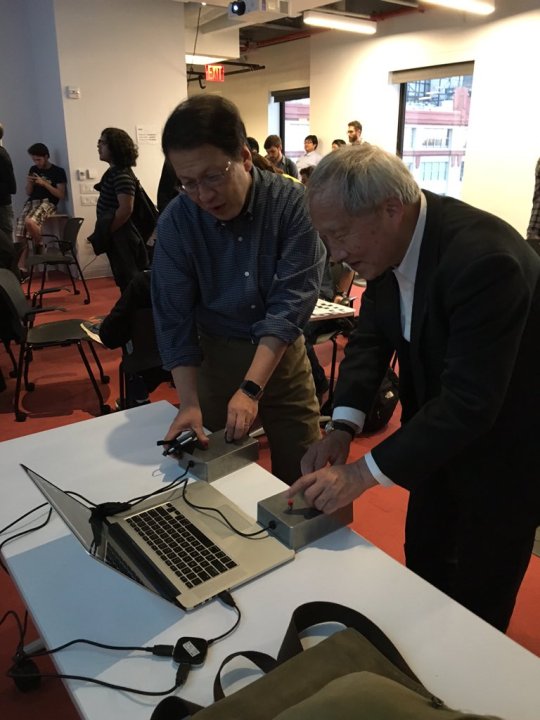

That photo is from a playtest I ran at NYU Game Center a few weeks before it was installed. The man on the right is Masayuki Uemura, who ran Nintendo’s R&D department during the development of the Famicom and the NES, who happened to be there to give a talk later that evening. From across the room, he immediately recognized Tennis For Two, and came over to play it.

After about 5 minutes he looked at me and said, “Quite simple, isn’t it?”

You can see Tennis For Two, and a lot of other cool parts of New York history at the New York Historical Society as part of “Silicon City: Computer History Made in New York” through April 16, 2016. For best results, bring a friend to play against! If you’ve got a fun project and you like what you’ve seen here, get in touch: ben at dozeneyes dot com.

This post originally appeared on my tumblr: gamedesignerben.tumblr.com

Follow me on twitter: @gamedesignerben

You May Also Like