Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Various thoughts and experiences from my time spent working in the games industry. Achieving financial independence and proceeding onwards to meet eventual failure.

This article is a vague collection of ruminations on indie game development, success/failure, my past work, and some general thoughts about the industry as whole. There's something of value in here, but exactly what that is I'm not so sure.

[Brett, Dave, and James at MAGFest 2015. The main Glass Knuckle Games team, minus Owen]

"Success" is a vague term in the indie community. Many would agree that success implies financial freedom. Of course, there can be numerous other qualifiers for success. Things such as: achieving a creative vision, having numerous fans, being well-known, leading a team, inspiring others, or even just hitting X number of sales. For the purposes of this article, we'll stick to the most popular definition. Making enough money from your own independent games to not have to hold another job. Financial success means you have the ability to work on indie games full-time - a dream for many developers. Not to say that other factors aren't important, just that they're much harder to define.

That said, this article discusses the financial aspect of indie development quite a lot. Speaking for many indies I know, we don't want to deal with money at all. We're making games because that's what we love doing. However, we live in the real world where money keeps the rent paid and food on the table. If you get nothing else from this article: indie developers stress over money very often; not out of greed, but need. Put us in a reasonable space where our expenses are taken care of and we'd happily work on games all year-round. This wasn't written as a complaint-piece. We all know that games are an entertainment industry. Like all other entertainment, we're not making essential products. We live and die, figuratively, based on demand, marketing, and the quality of our own work.

Unfortunately, for the vast majority of indie developers, financial success is unattainable. Some have just started their journey, releasing small games in to the nether where almost nobody will ever play them. Others are much further along, working with experience under their belt, completing games and seeing modest sales. On the other end of the spectrum, a handful of indie developers have released their own games and achieved financial independence. If you haven't already heard, the ratio of “successful” developers to everyone else is extremely small. There are numerous other articles out there re-iterating the “don't quit your dayjob” mentality when it comes to indie games. At it's core, this may come close to that same idea; but I've written this whole thing to share my own experiences with both success and failure.

[One of the trading cards from Noir Syndrome. Art by Steff Egan]

There was a time when I was a part of that small handful of success stories. I achieved financial freedom as an indie developer. And then I lost it.

As melodramatic as that sounds, it's the truth. In order to understand where I'm coming from, I'll provide a little background on myself and my work on video games. My name is Dave Gedarovich, Co-Founder of Glass Knuckle Games (along with Brett Davis). I have been in love with games since I was a little kid. Many others out there can say the same. It's a common hobby. However, almost as long as I've loved playing games, I've loved making games. I'd always be creating my own games - even before I knew a thing about computers. Vague paper imitations of the various RPGs or adventure games I was playing at the time. MSPaint maps and character pages. Crude dice-rolling battles featuring fantasy characters I'd seen on TV. I made my friends play them all. Watching someone enjoy my work (or even pretend to in many cases) was exhilarating.

Eventually I started delving in to rudimentary programming around middle school. I stopped paying attention in math class and started working on TI-BASIC games on my calculator every day. Luckily I kept my grades in order, but they were the least of my worries. Regardless, I finished heaps of text-based calculator RPGs over the years, always transferring them to my friends upon completion. They would beat them and provide valuable feedback for the next installment. It was at this point that I noticed people genuinely enjoying my work, instead of just putting up with it. I would often get requests for new games and features. This was probably one of the major influences in my decision to become a game dev in the first place. Seeing others enjoy something you've made is a driving factor for many developers.

Skipping ahead, after some time learning basic C++ and Javascript in high school, I was pretty much set on going in to Computer Science. While studying CS at Northeastern, I met Brett Davis, another avid game development fan. Together we started working on small browser-based games and formed our first studio, Glass Knuckle Games. That was over 4 years ago. After a couple small titles that we didn't take too seriously, I decided to start work on Noir Syndrome in my junior year. A procedurally-generated detective murder-mystery was a novel idea to me at the time. In addition, I felt that I had finally released enough small games to “go big” this time around.

[A screenshot from Noir Syndrome]

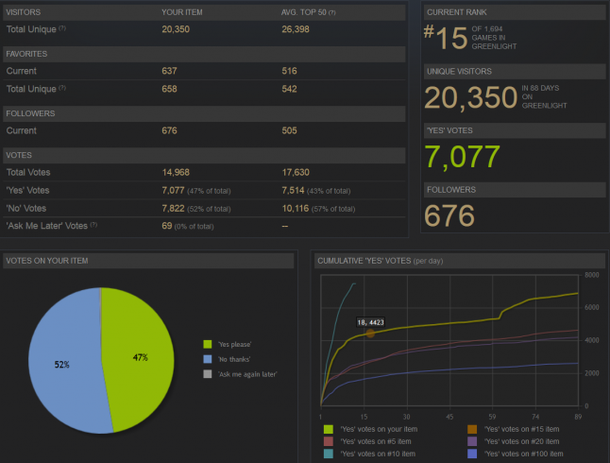

I spent the next 9 months working on Noir Syndrome in my free time. This was between work, school, homework, and other social engagements. As you can guess, this would boil down to 20 hours per week at the most. At the time, indie games were in the process of becoming a more mainstream subject. Steam had just barely started promoting their indie section, Indie Game: The Movie had just come out, and titles like Super Meat Boy, Fez, and Bastion were paragons of the industry. Steam Greenlight was also a huge challenge to overcome, requiring thousands of votes and often months even for “popular” titles to get through.

Shortly before finishing Noir Syndrome, we met James Johnston, a budding marketing student with a passion for video games. Although Brett wasn't working on Noir Syndrome himself, he agreed to let James join the team to help promote the game. Together we came up with a plan to put the game on Greenlight, market it as best as we could, and sell it on Steam and Google Play.

Despite knowing next to nothing about marketing video games, we were somehow able to pull it off. Noir Syndrome was a surprising success. On the first day alone we made thousands of dollars. For a student just working on this small project in my free time, this amazed me. Sales kept up steadily over the months until the Steam Summer Sale came around. For some reason beyond our knowledge, someone at Valve picked Noir Syndrome to be in one of the community choice votes. That vote won, and Noir Syndrome made tens of thousands of dollars in a single day. This absolutely blew our minds, and we were very much aware of how lucky we were to be a part of that vote. I had just made more then a years worth of my part-time job's pay in a single day.

[Noir Syndrome Greenlight stats shortly before it was approved for release]

However, even without counting sales from that day, Noir Syndrome was doing exceptionally well for the tiny budget it was made on. Again, this article isn't necessarily about money, but people are always goading indies to share sales figures. For the sake of those wondering, Noir Syndrome made over $100k in the first few months it was on sale. It's still available for purchase, but sales have since slowed as one would expect.

To put it in to perspective: I was just some no-name student making games for fun in-between college work. Given that I worked alone on the game and paid small sums out-of-pocket for audio and marketing before release, this was an overwhelming success. While these sums would seem pitiful to larger teams paying numerous developers, this was a huge win in my book. This was enough to gain complete financial independence for a few years, with plenty left-over to spend on contractors and various work for my next project.

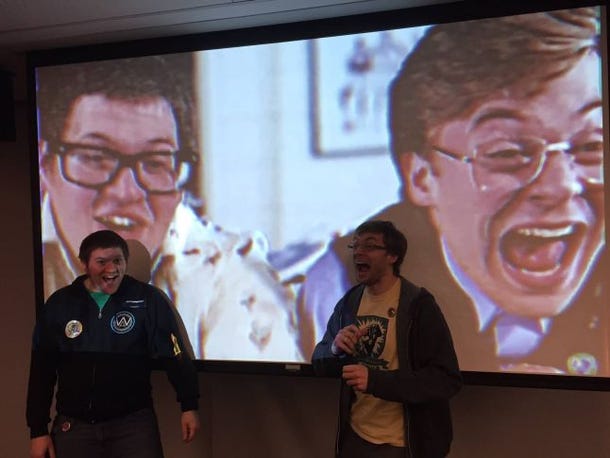

Not long after Noir Syndrome was completed, Brett (and our new artist, Owen), released Thief Town. Being a local-multiplayer-only game, it understandably sold less then Noir Syndrome. However, it did still make a sizable amount. As you'd expect of any business, a portion of our sales went back in to the company to help fund future endeavors. Regardless of sales, Thief Town was a hit among our fans. Many loved the wacky trailer we put together for the game, and still recognize James and Owen as “the Thief Town guys” to this day. At conventions, Thief Town would always draw a huge crowd of people smiling from ear-to-ear while yelling at their friends in excited frustration. Kids loved the game too. Although they had never planned to market the game to kids, there were always groups of children coming back throughout each convention to play with their friends.

[Owen and James mimicing their Thief Town characters at a public event]

With our two biggest titles out of the way, that brings us to Defragmented. Using a chunk of the funds we had from our past work, I set out to work on my next project. I wanted to create a very fast-paced cyberpunk Action-RPG with a top-down perspective. James had a knack for writing emotional storylines, so he joined the project to handle both writing and marketing. I knew that I had the skills and the time available to complete this game with absolute certainty. There was no doubt in my mind that the game would be finished, even if it took twice as long as Noir Syndrome. In the end, it did take twice as long as Noir Syndrome – nearly 18 months – to complete. However, this would probably be something closer to four times the amount of hours spent, given that I was working on it full-time.

.png/?width=610&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

[A screenshot from Defragmented]

There was a lot we wanted to do with the game, a huge soundtrack, a thick story, deep meta-game elements, and plenty of content for players to enjoy for many hours. In order to fund extended development on the game (along with hiring some extra contractors) we decided to turn to Kickstarter. Being our first time on Kickstarter, we failed miserably. There's plenty of other Kickstarter failure posts out there, so I won't go in to too much detail about that. In essence, we couldn't drum up enough interest in time.

Luckily we had solid plans for when the Kickstarter fell through. We still intended to deliver on all of our promises; we would just have to cut back on the amount of content and number of musicians that we could fit in to the game. We did eventually succeed in still creating a pretty stellar soundtrack, which is probably the most well-received part of the game. All of the features and content we wanted to put in to the game made it; but we always wonder what we could have done with even more time and funds at our disposal.

[James, Alyssa (our sound designer), and Dave at PAX East 2016]

We finished the game, but then what?

In the end, we did loads of “marketing” as best as we knew how. The amount of devlogs, facebook posts, images, shares, videos, conventions, tweets, streams, packages, and especially emails throughout development were absolutely massive in comparison to our past games. We ended up sending out at least ten times the amount of emails as we did with Noir Syndrome (and that's a very conservative estimate). We were lucky enough to get a few reviews and articles about the game around release, but those combined with our rather small fanbase were not enough to make the game profitable. Obviously our financial failure is not on the press, as there are so many factors that go in to a game's sales that it could not be singled out that easily. For the sake of being transparent about sales, Defragmented has yet to break the $10k mark. At the time of writing this, it has been available for about half a year. Over $10k has gone to music and contract work alone, so the overall result is a net loss (not even counting time spent).

This isn't exactly a post-mortem article either. There's plenty of flaws in Defragmented that can be correlated to poor sales. We have conflicting artstyles, the UI is too heavy, the game is too difficult, we didn't market well enough, the visual-novel cutscenes aren't enjoyed by action fans and the action-gameplay isn't enjoyed by visual-novel fans. All of those are fair points, among many other things. I'm not here to say that any game is more deserving of success then others. This is more of a fair warning to developers or even those aspiring to be developers. Failure happens, far more then you'd expect when getting in to the industry. People can succeed with one game, go “full-time indie” and then release a flop. Given how much time and how many resources go in to creating a game, a single bad release is enough to bankrupt a developer.

I'm lucky enough to not be completely poor after releasing Defragmented. I had the foresight to save up enough to live comfortably for at least a while, even if it had sold nothing. An emergency fund is always a good thing to have, no matter what sort of work you do.

We don't have any plans of closing up Glass Knuckle Games either. We still love our fans and will continue to make games, even if it has to be a part-time deal. Brett, James, and Owen have always been working on the studio part-time, so any major lifestyles changes would be down to me alone. I'll never lose my passion for making games, so don't expect a little failure to put me down anytime soon. In fact, I've been working on a new title, Heliophobia, over the past few months. If all goes well, it should be finished and available to the public sometime next year. Like all of our other games, it's a completely new style and genre for us, so who knows what will happen.

[A big collage of characters from almost every game we've made prior to Defragmented]

This is pretty much where things stand as of now. That little bit of success made the sting of failure much worse then it had to be. In reality, it's not that awful. Working on indie games full-time was a dream come true. Even if it didn't amount to financial stability, I thoroughly enjoyed every minute of it.

As I stated at the top of the article, I hope you found something of value in all of this. I haven't found any previous stories of indies who had succeeded and subsequently failed – or, at least none in which they share their experiences. It's hard to talk about, but good for the public to see. All of these indie success articles you see floating around don't properly represent the vast majority of developers. It's a wonderful thing when an indie game succeeds, but know that there are thousands behind it that failed.

Follow your dreams, quit your dayjob, just have a backup plan ready for when it all falls down.

-

If you want to talk to me about anything at all, you can find me on Twitter.

You May Also Like