Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Like many developers, Flight School Studio wasn't sure if its game, Creature in the Well, would have the legs to be a full-fledged product.

August 21, 2019

Author: by Bryant Francis, Kris Graft

Like many developers, Flight School Studio wasn't sure if its game, Creature in the Well, would have the legs to be a full-fledged product.

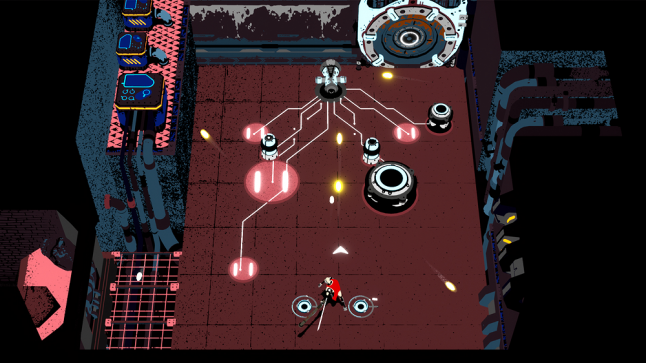

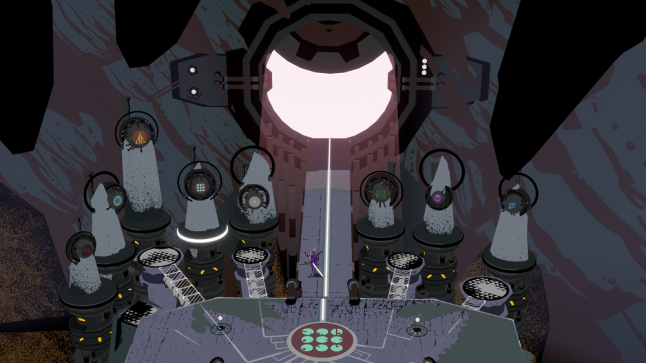

A Zelda-meets-pinball video game, Creature in the Well combined elements that were familiar, in turn making something that was somewhat unfamiliar.

But after some introspection and elbow grease, lead developers Adam Volker and Bohdon "Bo" Sayre refined their vision to make something that, with any luck, is digestible and fun for a wide audience.

Designing a Zelda-inspired adventure game that uses pinball-style combat is a unique proposition. So trying to convey what the game is and how it works has been a challenge for the development team from the get-go.

Volker said combining those two elements, adventure game tropes and pinball mechanics, required careful balance so that players could understand the game.

"We sort of operate on the design philosophy that was stolen from filmmaker Steven Spielberg," he said in a recent GDC Twitch stream. "His company, Amblin Entertainment, put out this idea that audiences like newness in sort of like a 70/30 relationship."

That means, Volker explained, that 70 percent of a new concept is familiar with the audience, and the remaining 30 percent it something that the audience may not be so familiar with. But the ratio would have enough familiarity to remove some of the unknowns that could put people off.

For Spielberg, it was "suburban California except there’s an extraterrestrial that befriends a small boy." For Volker and Flight School, "it's swords, but they don’t behave the way you expect," or "It’s a dungeon crawler except it’s a room full of pinball mechanics."

Volker added, "I think if it were all super abstract and new we would have a lot more work to do to tell people about it. But I think it’s important for players to look at the game and go 'oh I can see how that could be fun,' and 'I understand the format of how I’m going to play that.'"

This is the challenge of games with unique concepts -- communication. Innovation in game design often requires more explanation, and it's up to game developers or clever marketers (who, these days are often one and the same) to make abstract ideas more digestible and in effect, more sellable.

"You should be able to speak the language [of the game] fairly quickly even if there’s a lot of newness," said Volker. "So that’s why we went with swords and that’s why we went with dungeons and rooms and boss fights and connecting them all that way.

"The first time we played it at GDC somebody called it a pinball hack and slash and then the next PAX East show we brought it to somebody who [called it a] 'pinbrawler.' [Finding the language is about] players being able to tell you, 'You know, this is how I would describe it to a friend.' So it’s kind of just about listening, I think."

As with practically any game that's been developed, there were points in time where doubt reared its head. Volker said midway through the game's development, Nigel Lowrie, co-founder of publisher Devolver Digital, played the game and was dubious about whether the game would be scalable into a full game experience.

"That was really hard feedback to get but was really helpful," said Volker. "We sort of had this big moment where we were like 'ok, let's gut everything that we’ve built.'"

At that point, fellow developer Sayre took a week off of his regular development tasks, and made eight example dungeon rooms in an attempt to create unique puzzles, each with significantly different mechanics.

"He actually had to create a bunch of new stuff for that," said Volker, "But it was really good to try to take the pinball hack and slash mechanic and spread it out as wide as it could be so that players got something different as they played through the entire game, and it wasn’t just hundreds of rooms the same stuff."

Volker said, "Once he built those example rooms we reviewed those for their uniqueness and then I tried to build the dungeons based on his example. That’s kind of how our design process worked. Bo would be like 'I think this has something unique, this is what I was going for,' and then I would expand it into the dungeon and then he would have an idea to make a room and we would fine-tune each other's designs.

It was that external feedback, and Flight School's willingness to take that feedback seriously, that put the game on track to become something better. "That was really one of the toughest parts of getting a whole game," said Volker. "It was kind of always a prototype until that moment, I think."

The issue with feedback, however, is that there's often a lot of it. Parsing what feedback to act on and what to ignore is an age-old problem.

For Volker, evaluating feedback is a discipline of self-awareness and honesty. "You know, sometimes you don’t want to hear [feedback] and sometimes it doesn’t matter," he said. "How stubborn do you want to be? [That] is the kind of question you have to ask yourself. Like, it's when you believe in something, and then you have to decide whether you’re lying to yourself about its quality."

Volker said acting on feedback requires a bit of self-reflection. If people criticize your game, maybe the game your making is suited very specifically to your own tastes, and perhaps not so appealing to people in general. He said Flight School would carefully watch new players play Creature in the Well and try to identify their excitement, or lack thereof, and consider whether or not the game was resonating with people.

Volker said, "I think in the case of Nigel’s feedback it wasn’t 'this isn’t a game.' He said, 'I don’t know if this is going to scale to a full experience.'...He hadn’t played a lot of it, we were in the middle of development, I don’t even know if he knows how important [his feedback] was."

The most valuable part of the mid-development adjustment can simply be termed as full-on reevaluation. Volker and the team asked tough questions, not just about the game's design and concept, but whether or not they should keep going on with development of the game.

Fortunately, Volker and crew were convinced that, with Creature in the Well's strong core mechanic and familiar influences ranging from Breakout to pinball to Zelda, they had an appealing game on their hands.

"Once we [reevaluated the game], we were like, 'well we still know that these other basic games are fun,' so there’s something here -- we just have to work to find it."

For more design insights from Creature in the Well, you can watch the full chat with Adam Volker below.

You May Also Like