Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Today's Playing Catch-Up, a weekly column that dares to speak to notable video game industry figures about their celebrated pasts and promising futures, speaks to "Electr...

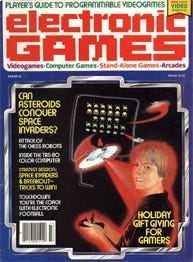

Today's Playing Catch-Up, a weekly column that dares to speak to notable video game industry figures about their celebrated pasts and promising futures, speaks to "Electronic Games" co-founder and the man behind the infamous "Game Doctor" persona, Bill Kunkel. In 1981 Kunkel, along with long-time friend Arnie Katz, launched 'Electronic Games,' the world's first consumer magazine dedicated entirely to video games. With what was essentially a monopoly in a rapidly growing industry, 'Electronic Games' enjoyed three years of massive success before the legendary video game crash of 1984 halted production. Kunkel, the Video Game Crash Expert? "There were a lot of factors to the crash," Kunkel told Gamasutra, "we tend to simplify it these days." Most will remember the oversaturation of the market, pointing fingers at the piles of less-than-desirable titles sitting unsold in shops. And, of course, there was the overabundance of video game consoles, with the Atari's new line directly competing against their own 2600. Most, Kunkel says, tend to forget that even the arcade industry was collapsing at the time. "They got suckered into laserdisc games," said Kunkel, referring to games such as Dragon's Lair, which were little more than streaming videos and tests of memorization. "At first it spread out the business and helped them," he said, "but pretty soon - with the high cost of the machines, and players figuring out that they weren't all that great - you had arcades all over the country sending back the machines. It basically transformed the arcade industry from one that had the best developers, the most original ideas, best graphics and presentation for every game, into glorified networks of home video game systems, because they were all kits. They were buying the one cabinet, and when a new game came out, they'd slide in a new title, new art, new board... the Neo Geo thing." "I think a lot of people believed that video games had served their purpose, that they had been the foot in the door that enabled us to get on the computer and do really serious, important things. We went through a period near the end of our run where we were told by the publisher and the last saleswoman we had that we should avoid using terms like 'games' and 'fun' in our copy. It wasn't a game, it was a simulation."

Kunkel the Game Designer After leaving Electronic Games behind for good, Kunkel, along with Katz and his wife, Joyce Worley, formed Katz Kunkel Worley Inc. (KKW) and soon after, its software subdivision, Subway Software. "Brian Fargo at Interplay contacted us and said, 'Okay, you guys have a lot of opinions about games, how would you guys like to do one?' So we wrote Borrowed Time, a text adventure. And remember, this was a time before there was such a position as 'Game Designer.' Most programmers believed there would never be anyone who was a pure designer working on a game who was not a programmer. And this was not an isolated opinion, it was commonly felt that you had to understand programming to make a game. We were one of the very few pure design houses, I suspect to this day." Subway Software designed a number of other games as well, including Omnicron Conspiracy and Superman: The Man of Steel for First Star Software, and WWF Wrestling for MicroLeague Sports Association, considered the first true computer wrestling game, along with the first to use the WWF license. "It was digital capture," said Kunkel, "WWF would send us films of fights. We had menus on each side of the screen, you chose your move, the computer calculated your move against its, and you saw a slideshow of the move being done." Kunkel and company also continued magazine writing through this time. "We spent '85 through '87, I think, working for computer magazines, one of which was 'Analogue.' And the guy who owned it, Lee Pappas, sold out his stuff to Larry Flynt. He hired Andy Eddy to edit 'Video Games & Computer Entertainment,' [today Tips 'N Tricks], who subcontracted to us to do all the computer writing while his people did the console side. Kunkel said that he wasn't completely happy with this position, being a console gamer at heart. "In 1990 I ran into Steve Harris at CES, who was doing Electronic Gaming Monthly very successfully, and that led to us starting Electronic Games again." Electronic Games saw a brief resurgance thanks to Harris' Sendai Publications, though Kunkel's role was limited strictly to copy. "The big problem there was that we just produced the copy and sent it off from Las Vegas to Illinois," said Kunkel. "We were like the redheaded stepchild. A new layout person would come in, and they'd practice on our magazine first, and maybe eventually 'graduate' to EGM. But it was a really good deal - the magazine was making money right until the time that it collapsed."

Kunkel the Dot-Com Victim KKW, Inc. broke up in 1994, and Kunkel hooked up with Ed Dille and Barry Friedman at Fog Studios. "We did real well," said Kunkel, "we worked with websites and stuff, during the dot-com boom. We had a sweet deal with Prima too doing these game strategy books. We would get a team in there to play through the game and do screencaps, I would write it up, and we could get it done in a couple weeks. The only problem we ever had was that the game developers never wanted to talk to us, because they weren't making any money off of it. They'd send us a game, and the game would play twice as fast as it was supposed to. So the book would say something like, 'you have to execute this move very carefully,' when it might be the simplest thing in the world at normal speed. I'm sure some people wondered what the hell we were talking about." At Fog Studios, Kunkel found himself involved with Happy Puppy, a hugely popular gaming website of the time. "We ended up tangled in a huge lawsuit with someone who called themselves Attitude Network," he said, "who had purchased Happy Puppy. Ultimately we won the case, and a genius - I won't name names - suggested we take stock in something called globe.com." Globe.com was, as many may remember, a major victim in the so-called dot come bubble burst. "The stocks were worth $75,000 at the time, but the remaining money the end was about $25,000. "There's nothing quite like being unable to sell stocks you own, and every day you're watching and it's dropping, dropping. It was one of the most horrible experiences of my life." Professor Kunkel Kunkel began teaching a class on basic game design at the University of Nevada Las Vegas in 2003. "We taught them the realities of game design." said Kunkel. "It was successful enough that in the second year we did it we did an extended course, Advanced Game Design. We had about twelve people in the class, and we broke them up into groups of three and four, and each one of them was to produce a game design pitch document they could sell, produce storyboards...everything that you would need to sell a game. They went to work at it, and the student who lead the team who produced the best game and won the contest is now working at Petroglyph Studios," he said. "It was a lot of fun. But since we're preparing to move out of Las Vegas, I didn't take the classes this year." Kunkel the Author "A friend of mine, Cav, ran this thing called Classic Gamer Magazine," said Kunkel. "It's kind of a tribute to Electronic Games, since Cav was one of those people who was 12 years old when the first issue showed up on stands. It had this great impact on him. I had been writing columns for Good Deal Games and Digital Press, and the memoir stuff was going really well, and Cav suggested I write a book. I said, 'Who the hell would publish a memoir?' and he said what about Lenny Herman?" Leonard Herman is the owner of Rolenta Press, and has published a number of industry-related books, including Ralph Baer's 'Videogames: In the Beginning' and Herman's own 'Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames.' "He was happy, to do it," Kunkel said. "So I rewrote the memoir articles I'd done, and added more. When I first started I had a five-page list of stuff I wanted to cover, and at the end, I realized I didn't even cover half of them! It was a lot of fun, it put me in contact with people who I hadn't spoken to in decades." "It's a little bit of everything, it's mostly fond memories really. I had a great time writing it. There's some serious stuff too, some of the people the industry's lost, like [M.U.L.E. designer] Dan Bunton and Ken Uston, the blackjack legend who wrote 'Mastering Pac-Man.' One of the nice things I think people will see in the book, is how much kinder and gentler the industry was in the '80s and even the '90s. It was kinder, and it was wilder! Today, everyone has a stick up their ass, working with these awful deadlines and with no overtime. One of the things I teach my students is, this is not a dream job guys! So that's the reality of it. These kids are exploited. I used to write comic books, I know the way these businesses work, where starry-eyed kids will go, 'I'll do this for nothing,' and then they do." Kunkel the Game Doctor You can't keep a good Game Doctor down, and Kunkel still has a few things to say about the state of the industry. "My big problem is that they kill these systems too soon," said Kunkel. "There's no other consumer product like that. Imagine if the video format changed every three years. You look back at the Commodore 64, and near the end of its life companies like Cinemaware were distributing games that were almost indistinguishable from early Amiga products. It clearly had life in it." "Sony's smart!" he continued. "You don't come out with a new system THIS YEAR, people are just learning how to do stuff on what we have. The Xbox 360, to me...it's a very questionable system and a very questionable idea. I say, let these system have ten years, let developers find all the little tricks. It's like if you're a painter, and they give you a million more colors to paint with every three years. 'But I need time to experiment with all these colors!' you might say. No. The canvas keeps getting bigger, and ideas are getting smaller. There are so many sequels, and so few new ideas." "No more Tony Hawk games, okay?" The Game Doctor concludes. "We've had enough goddam Tony Hawk games. I don't care how much you love Tony Hawk games, you don't need any more. Just stop it." [UPDATE: 2.35pm PST 12/14/05 - corrected game publisher information from Epyx/Capstone to First Star Software.]

You May Also Like