Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

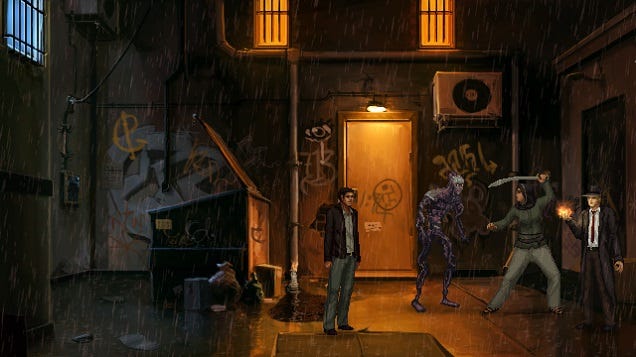

Unavowed sees the player returning to their life after being possessed by a demon, and follows their decisions as they face a greater imminent darkness.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

Unavowed, which has been nominated for Excellence in Narrative, sees the player returning to their life after being possessed by a demon, and follows their decisions as they face a greater imminent darkness.

Gamasutra spoke with Dave Gilbert, writer, developer, and programmer for Unavowed, to talk about the nuances of drawing the player into your characters and stories, how control over the narrative can grant a greater sense of immersion, and the thoughts that go into making player decisions that truly matter.

My name is Dave Gilbert, and my primary role on the game was as a writer, developer, and programmer.

I downloaded Adventure Game Studio waayyyy back in 2001. After spending about 5 years making freeware games, I decided to give the full-time commercial developer thing a whirl, and haven't looked back since. We've published over fifteen games, including the Blackwell series, Primordia, Gemini Rue, Technobabylon and most recently, Unavowed.

Back in 2013, I read an interview with a former BioWare writer about how she longed for the ability to skip the combat sections in narrative-based RPGs. The logic was that action-based games let you skip the narrative, so why not the reverse? This sounded like the point-and-click game of my dreams - the classic party-based branching narrative of an RPG, but in a point-and-click adventure game? Sign me up.

Someone was bound to make that game sooner or later, but nobody ever did. So in a fit of hubris I decided to make that game myself! Unavowed was the result.

We primarily used Adventure Game Studio, a freeware tool that is used to make point and clickers. The engine is a bit dated these days, but it handles so much of the grunt work and does everything we need right out of the box.

I wanted to start the game off with a bang, and the visual of starting the game in the middle of an exorcism was too good to pass up. And, after playing around with the idea, it fit the themes of the game perfectly. It gets the players invested, it gives you a reason to enter this supernatural world, and it gives you a clear goal to achieve.

As for why that idea specifically... I don't know! It just came to me from that place that all ideas come from. When it came to me, it just felt right. So I went with it. Sometimes that happens.

There are no hard and fast rules for this kind of thing. Any rules or theories I come up for myself I tend to set on fire whenever I start a new project. That said, the key thing for me is to make it personal. I try to make an emotional connection to the characters and stories I am creating, because that's the only way I can build that same connection with the audience. You can't fake that kind of connection, so building that within myself is what I spend a lot of time doing. Without it, the spark just isn't there.

I mentioned earlier that I try and create a connection to the characters and stories I create. If I am successful in doing that, then it gives me unique insight into what a difficult choice could be. If *I* am torn on a particular choice that my characters are faced with, then most likely the players will be as well.

For Unavowed, I am particularly proud of how the Big Decision at the end of the Brooklyn mission turned out. I still don't know what the correct choice would be, and many players have said the same thing.

As I said, I was very inspired by that 2013 BioWare interview. My favorite part of the mid-era BioWare games (which I define as from the original Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic to the first Mass Effect, before EA took over) was the party companions. You make a deliberate choice about who to take with you, and your choices get rewarded in many small and subtle ways. Your party members will react to the world, other characters, and your choices in different ways. And often, I would go back and replay old sections with a different party to see what changed.

It's a style of narrative design that isn't made much anymore (even BioWare seems to have given it up), so I wanted to recreate something similar. But instead of your party members changing your tactics in combat situations, it would instead change how you solved various puzzles.

It's just that. Give the player control whenever possible. I tend to put more emphasis on immersion and interactivity than puzzles (much to puzzle fans' dismay), but I really want to put you within the experience. Nothing takes that illusion away more than taking away control, so I try to avoid that. I am not always successful (the climax of the Unavowed's Wall Street mission is Exhibit A), but I do try.

As for conclusions, I think designing a game with multiple endings in mind is a bad idea. Inevitably, one of them will be less satisfying than the other, and I didn't want to ever tell the player that they played my game "wrong." Any choice you make is valid, and the reward comes from seeing the results of that choice play out in small ways over the course of the game. I never want to cut the player out of content just because they made a particular choice.

You May Also Like