Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Jörg Friedrich of Paintbucket Games discusses the studio's first game Through the Darkest of Times: - the "use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations" in games in Germany; - "prototype first, document later" principle; - balancing the game.

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on March 12, 2020.

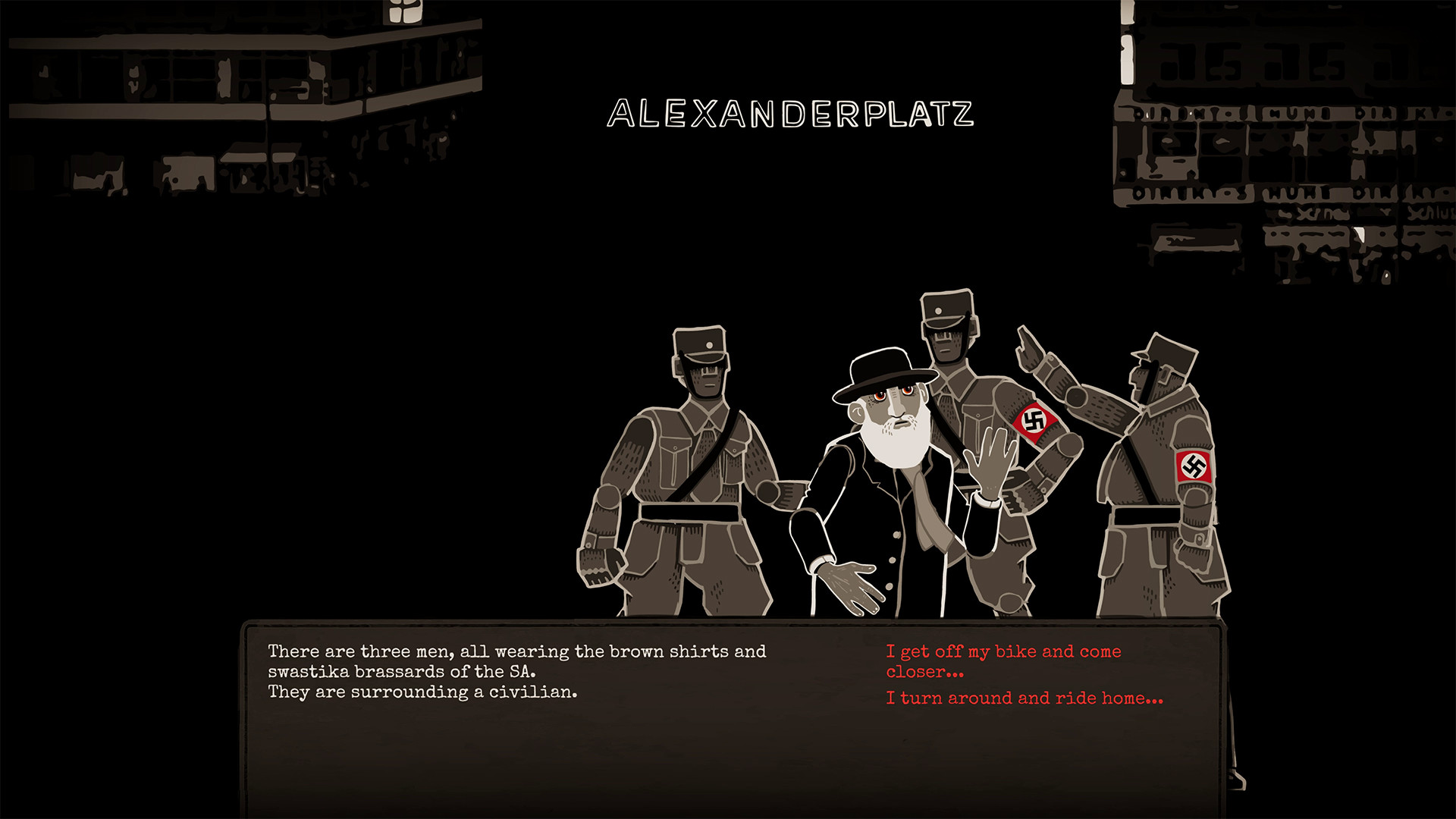

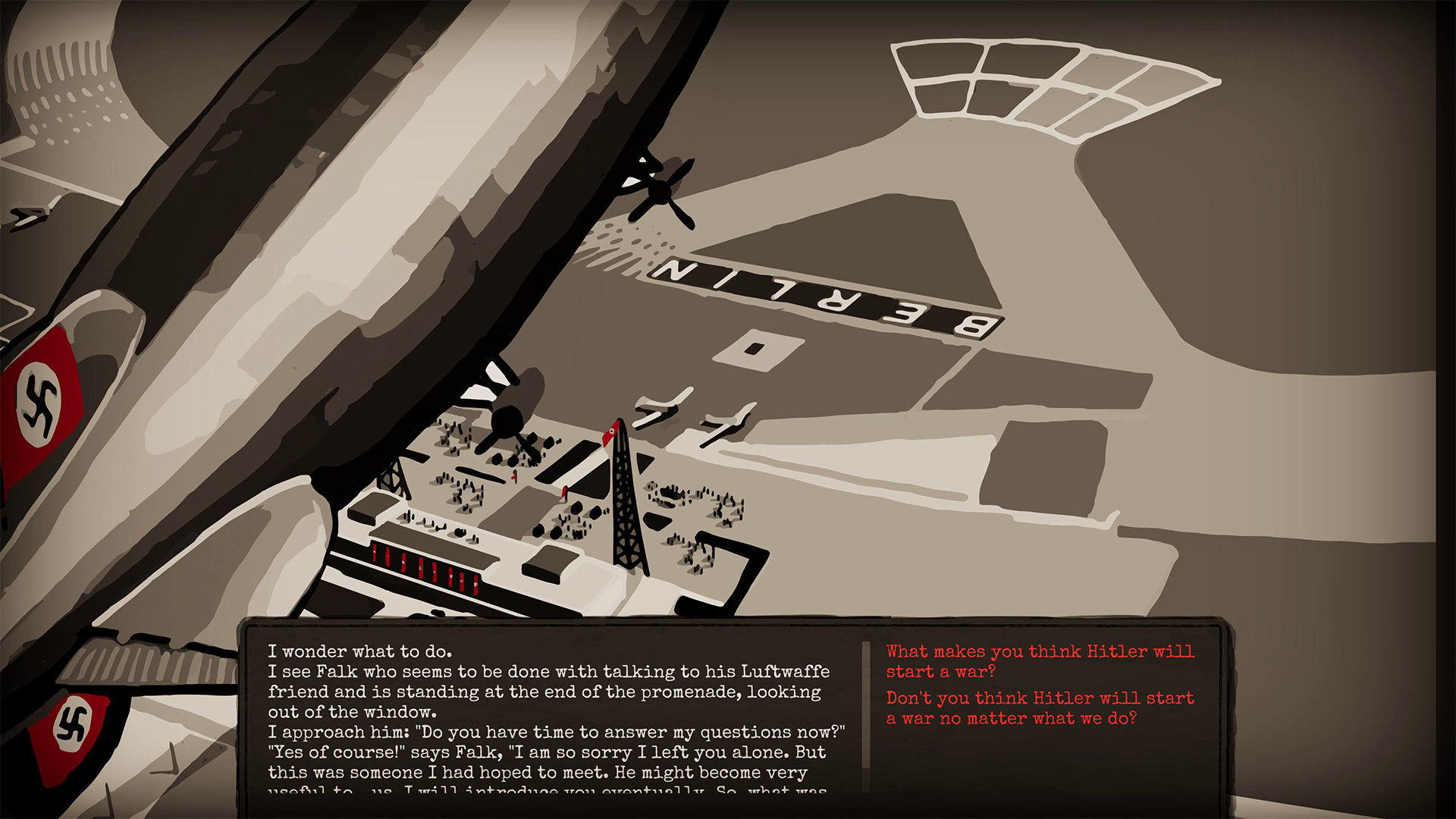

Strategy game Through the Darkest of Times came out on January 30 to very positive reviews on Steam. The award-winning indie title chronicles the struggle of a small resistance group during the years of Nazi rule in Germany.

We caught up with Jörg Friedrich, creative director on TtDoT and co-founder at Paintbucket Studios, to discuss the creation of the game that is also a compelling history lesson.

Jörg Friedrich

Oleg Nesterenko, managing editor at GWO: Jörg, before going indie, you worked at Yager Development. What was your role at the company?

At Yager, I started as a level designer on Spec Ops: the Line. While still working on the game, I switched to game design with a focus on AI. And then, because I had to develop AI, I started teaching our level designers how to build levels so that AI could work in them. That brought me back to level design, and I became the lead level designer on Spec Ops.

Spec Ops: the Line (2012)

After we shipped the game in 2012, publisher Deep Silver approached Yager. They were looking for someone to develop Dead Island 2. I made the concept for the game, which they liked. So we started developing Dead Island 2, with me attached as design director. I worked with a team of around 25 game designers and level designers. Altogether, there were 140 people or so working on the title.

However, in 2015, the project was taken away from Yager over creative differences. That was a hard blow. Yager did a really good job trying to keep as many people as possible. While they wanted to keep me around, I declined. I had been with them for nine years by then. Plus, my good friends had to leave the company. Plus, I had wanted to go indie for a long time.

What was wrong with working on AAA stuff?

I got into that industry because I liked making games. But the higher up I got career-wise, the less I had to do with games. With Dead Island especially, I was mainly managing that team, managing the relationship with the publisher. It was just lots of meetings, I barely even touched the game. I was missing that.

But you didn’t go indie right away.

No, I did not. A small Berlin-based studio called Sandbox Interactive made me an offer. They were making a sandbox MMO called Albion Online, and they wanted someone to build up their team and creative structures. That’s what I did there for two years as creative director.

Albion Online (2017)

I found it interesting because they didn’t have a publisher. They were basically indie but with the money from an investor. Plus, they had a very close relationship with their player base. And it was a live game. It was all new to me.

Still, I always knew that it was just going to be a gig. It was not my project. With Spec Ops, I had worked on it from the very beginning. Dead Island 2 meant even more to me because I was the one who made the pitch for Deep Silver. But Albion was already running when I arrived.

So when my contract ended, I left. I went on to teach game design and narrative design at different universities. In the meantime, I started working on what eventually became TtDoT.

How did you come up with the concept for the game?

The end of 2016 was the time I found politically very challenging. Trump just became president. The UK voted for Brexit. Right-wing parties started to pop up in Germany, France, Poland, Hungary, and so on. This stuff worried me a lot.

Through the Darkest of Times

I often met with my friend and fellow developer Sebastian Schulz to discuss this stuff because he is also very much into politics. We worked together at Yager and Sandbox. We also made smaller game jam stuff on the side just for fun.

Anyway, by the end of 2016 we felt like we had to do something about the political situation. We were considering joining a party or starting an initiative. But then we figured we should use our craft and make a game that might have a positive impact on things.

By then, I had had a concept for TtDoT for a while. I showed it to Sebastian, he really liked it, and that was the beginning of it all.

Through the Darkest of Times art

That’s how the two of you founded Paintbucket Studios?

At first, Sebastian still had a full time job at a Sandbox and I was doing a lot of teaching to pay my rent.

But whenever we had time, we were working on the game.

At some point, we applied for funding from Medienboard [a body responsible for Film Funding and Media Business Development in the states of Berlin and Brandenburg—Ed.]. They mainly do movies, but they also give public funding to game companies. They give you a loan, but you only have to pay it back if you’re successful. The money arrived in October 2017. We decided to take that leap of faith.

We founded Paintbucket in April 2018 and announced the game publicly. Sent out a press release and whatnot. Got a lot of feedback just for that concept which was really in a very early state.

And that’s a nice thing about being indie. You are free to just go to whatever conventions you want and have people play your game and give you feedback. With AAA, you need to hide everything from users. If you invite playtesters, they all have to sign NDAs.

TtDoT was the first game made in Germany to feature swastikas and refer to Hitler as Hitler. This had not been possible for 20 years. Could you tell us about your fight against censorship?

We decided to use some of our money to go to Gamescom 2018. In Germany, if you want to show a game publicly, you need to get an age rating from a semi-government organization called USK [Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle—Ed.].

We knew, of course, that if our game was to get an age rating, it couldn’t feature any swastikas or any other so-called unconstitutional symbols. This rule had existed in Germany for two decades.

We thought we’d just leave out swastikas. We didn’t want to make up any fantasy symbols. First of all, it would have been wrong for the topic. Second, we thought we’d just leave the space empty and everybody would know what kind of symbol belonged there.

So we brought our Gamescom demo to the age rating board. And that’s when we learned that it was not just swastikas that USK considered to be an unconstitutional symbol. Nazi salute, too.

And we have a lot of that in the game, right? We only planned to make one version of the game for both the German and the global market. And now they told us we had to rewrite a lot of scenes. That was… unfortunate [expression edited by morally upright censors—Ed.].

However, at that point we were in touch with another organization called game, which is kind of a lobby group for the German game industry.

Lucky for us, they were already negotiating with USK about changing the rules. And our game arrived just at the right time.

Long story short, they changed the regulations two weeks before Gamescom [For the long version, read Jörg’s blog here—Ed.]. We could now submit our demo including swastikas and Nazi salute and everything. We were the first game to get an age rating after the change, which got us a lot of attention.

We had tons of press. The game was in the main German news during prime time.

That’s when publishers took notice of your project?

Actually, that happened before the whole swastika discussion started. When we sent out the press release in April 2018, we immediately got a lot of media exposure just because of the theme. THQ contacted us and said they’d like to look at it.

I never thought they would sign with us because we were too small for them and the topic was way too niche-y.

But apparently, they got really interested. Plus, it turned out they actually did publish indie games too.

Like This is the Police, for example.

So in October 2018, we signed with THQ through HandyGames, which is their indie label. They further funded the development, which allowed us to hire two more people to help us, one artist and one programmer.

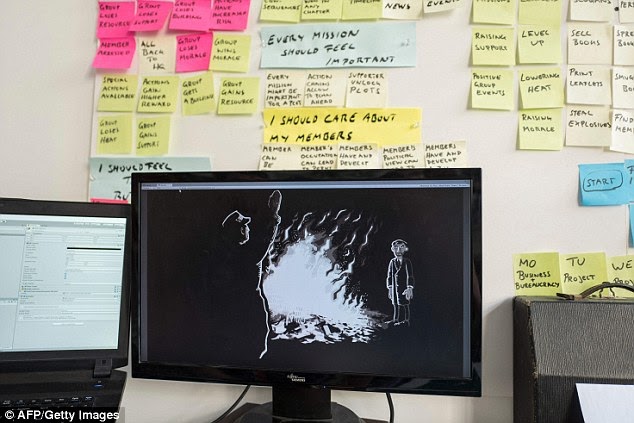

Let’s talk about your process. I saw this picture of your office with lots of stickers on the wall. Was that your design document?

That wall with the stickers is what I call the game’s DNA. It’s just high level goals rather than a detailed design document. It says stuff like “Every mission should feel important” or “You should care about your members” or “You should feel threatened but clever.” I like to put stuff like this out visually and physically. People can move it around. And if you feel like this goal doesn’t fit anymore, you can just rip it off and everybody on the team sees that it’s gone. You can also discuss stuff while looking at the wall and moving stickers around.

I am not a fan of writing very long detailed designs beforehand. You’re trying to document something that’s not there yet. I always go from asking what the game needs right now. Where are we with the game compared to our goals? Does the game deliver on them? Feedback comes in as well, which helps us understand what the game needs at this particular moment. Once you have identified your priorities, you build it as fast as possible and then document it.

So basically, first build something quick and dirty, try it out, and if you feel like it’s good, then build it better and then document it in all details. I think for a game like ours it makes more sense to implement stuff right away and test it rather than write in-depth designs to see that it doesn’t work in the end.

So at all stages, you always have a playable build?

Absolutely. Maybe there are certain parts of the game that are not playable right now because they are under construction. And maybe something doesn’t run for a day or two because it has to be changed drastically. But that should be an absolute exception. We always try to have a running game from the very beginning.

That sounds very efficient, and yet, it took you three years to finish the game.

Maybe we’re just slow [laughing—Ed.].

For the first year we didn’t really work full time on it. At this stage, we only worked on a playable concept. Even back then it was always playable. For the second year there were only two us most of the time. The game really started to shape up during year three.

But you know what? As small as the game might seem, it actually has a lot of content. For example, I wrote around 120,000 words for it. It’s almost 500 pages. The narrative, lines of dialogue, descriptions of events.

Of course, I didn’t expect it to take us this long. But you always take the time you have, right? We had an opportunity to take our time because we had a publisher. If we didn’t have a publisher, we would’ve probably had to ship the game in early access and with much less content.

Did the game change a lot over these three years?

Actually, the original vision was very close to what it became. That’s another good thing about being such a small team.

We always knew it was going to have these four chapters, we knew what events they were going to cover.

But the game grew in size compared to what I envisaged.

We planned to make it smaller originally because we were just one artist and one designer and had a very small budget. Less illustrations, less visuals and even more text. And maybe the roguelike aspect was supposed to be stronger. You should have been able to play through the game in two to three hours so that it wouldn’t hurt so much if you died on the way and had to start again and have a different experience.

So you just kept adding content? Did you have to discard any features?

In our first prototype, the player had a very clear goal. For example, they had to reach 50 supporters over the course of the chapter or lose the game. That made a lot of things easier in terms of game design. But it didn’t work narratively because it led people to mechanically pursue goals without thinking about what they actually meant in the context of the story. And I wanted to leave it up to people to decide how they want to play it and what goals they want to reach.

There was another really big feature that we canned. The so-called Tactical Mode. The idea was that before sending people on a mission, you had to actually plan it, move little icons on a timeline, assigning who does what and when. When the mission plays out, you only have very limited ways of interfering. You can either abort the mission, press on or hide. That’s basically the three cards that we now have in the game.

The tactical mode was nice, but we didn’t do it for two reasons. First, it would have really bloated the game. People would have spent so much time planning these little actions, which would have completely taken away the focus from the narrative part. Second, it would have excluded people who are not playing a lot of games. I aimed to make it accessible even to non-gamers.

When the game came out, many players complained that it was impossible to complete high-profile missions. Then there’s resetting your progress with every new chapter. Did you intend for this aspects to be unrewarding?

With such a small team at one point you really need to prioritize. And I think our priority was getting these events right, making sure everything is correct in tone and everything sends the right message. It took definitely more time than working on the game’s balance. That’s a shame, of course.

But this is the kind of stuff we’re looking into right now. We are trying to improve the balance with patches so that people can take on special missions if they want to.

It’s not easy, though, to achieve that balance because these missions are supposed to be hard.

I didn’t necessarily want to make these missions rewarding gameplay-wise. I didn’t want people to do them because they unlock super items or just out of completionism. I wanted players to be motivated by the narrative. Like if you take on a mission, it’s because you want to let the world know about Nazi crimes. This is why you enter a TV station, for example, and risk your life and the life of your group. You actually risk the entire game. You should be very clear that if you try this, you might not be able to finish the game.

I can see why this doesn’t work for some people, but it makes sense for the kind of game it is.

And what about the aesthetic of the game? What was your thought process behind that?

First of all, we had to go with the visuals that we could actually deliver. Clearly, we couldn’t make a photorealistic 3D game with just two people.

Second, I always wanted to make a more abstract game with lots of text. Text makes people imagine stuff. The same is true about an abstract art style: it leaves more to the imagination. With a topic like ours especially, games haven’t really found a good way of treating this yet, so it makes sense to allow people to figure it out for themselves.

Finally, we didn’t want to recreate the fascist aesthetic in the vein of Riefenstahl. Many games do that and even more movies do that. Even if they are about people fighting Nazis, they still kind of celebrate this aesthetic by showing off flags, weapons, blue-eyed and blond-haired characters. We did not want to glorify that. And that was when Sebastian found out about German expressionism, an art style developed in the 1920s in Germany. It moved away from the realism that you had before WW1 to a stylized, more abstract depiction of ugliness. It showed people the way they really were, broken and unsightly. We were inspired by artists like Hans Brosch, Heinrich Otto Dix and Käthe Kollwitz.

Finally, we wanted to make it black and white with only a very limited use of color. I never liked the idea of recoloring these old photographs from that time.

Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht, 1919-1920

Now that the game is out, are you already thinking about what’s next?

We definitely want to make more games that are different.

One project that we are going to work on is a game about prosecutors in West Germany in the 1950s who were trying to bring Nazi criminals to justice, try them in court. The rule of law is a theme that is under-represented in games. This project is very close to TtDoT in a way, it’s almost its spiritual successor. But it’s going to have a courtroom simulation element to it. The funding is already approved, so we’re likely to go ahead with it.

The other project I cannot talk about at this time. We would love to make something without Nazis. We’ll see.

Good luck with that and thank you for your time.

![]()

This interview was originally published on Game World Observer on March 12, 2020.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like