Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

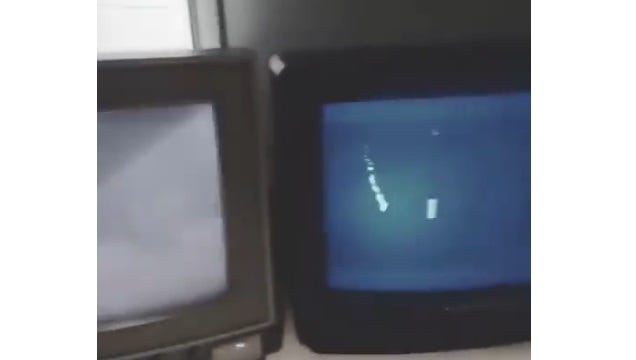

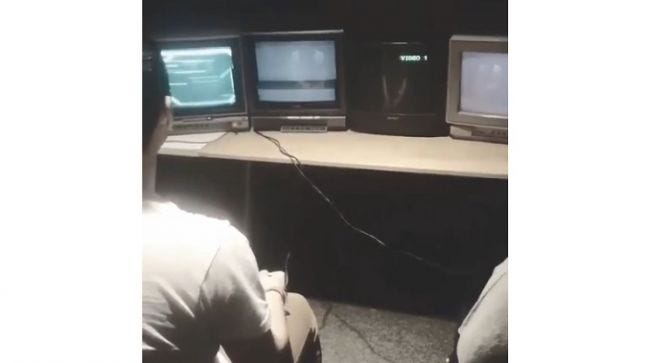

Cathode MK1 offers games across multiple CRT screens, forcing players to follow the game as it moves from monitor to monitor.

The 2019 Game Developers Conference will feature an exhibition called Alt.Ctrl.GDC dedicated to games that use alternative control schemes and interactions.

Gamasutra will be talking to the developers of each of the games that have been selected for the showcase.

Cathode MK1 offers games across multiple CRT screens, forcing players to follow the game as it moves from monitor to monitor.

Gamasutra sat down with Ryan Mason, developer of the Cathode MK1, to talk about the appeal of this kind of movement between screens, how this changes the player's perception of games played on it, and the ideas behind the games Mason has created to take advantage of its unique play style.

Ryan Mason, I'm the designer and developer of the Cathode MK1.

I started out learning 3D modeling for games back in 2007. For the next few years, I continued to build my skills as an environment artist, but also began working on UI and graphic design for games. After that, I really wanted to be able to build my own mechanics and started learning how to code in the Unity Engine. At the same time, I was learning how to use Arduino and started building games and installations that leveraged electronics and Unity. It all culminated in the Cathode MK1 during my final year at OCAD Univeristy.

I describe it as a platform for multi-channel games. A console that allows developers to use the hardware as a extension of the gameplay.

I had been collecting CRT televisions for a few months and really wanted to put them to use all together. I started tinkering with switch boxes and composite cables and realized how easy it would be to manipulate the signal and route it to different outputs quickly. From there, I figured out how to get Unity and Arduino talking to each other so that the game could control the signal path - and the rest is history.

Unity, Arduino IDE, Google Docs, and Twine for prototyping multistage puzzles.

As for the physical materials: a pile of CRT screens, an HDMI to composite adapter, HDMI cable, composite cables, RF modulators, an Arduino, 16 channel multiplexer, some phono jacks, wire, and solder.

The main challenge was that because my solution was super low tech, I could only have visual content on one screen at a time. In order to have all the screens active with unique visuals, I would need to either have X number of video sources, where X is the number of screens. OR I would need to have some piece of hardware in the middle that would convert a single video output from the computer into a matrix of video signals which would then individually feed into the CRT monitors. While technically possible, those solutions were way outside my budget and time frame.

Ultimately I settled on a solution that anyone could build for $30-ish. The challenge was then to discover what kinds of stories and mechanics that might be interesting on a setup like this. This discovery part of this project is still ongoing. The prototypes I have made thus far are just experiments in multi-channel game design.

I had planned the game That Night to be sort of a metagame. A game that takes place inside of the alternate universe that the console exists in. The game would also loosely reference a slew of classic video games such as Maniac Mansion, Monkey Island, and Another World in terms of aesthetic, mechanics, and controls. I imagined that this might help the game appeal to an older generation who grew up with these now "classic" games and who don't make gaming a big part of their life now.

Cube's Quest was based on the idea of active and passive players working together. While one player takes control of the main character, which has somewhat janky controls, the other controls elements of the environment that assist the active player in their movement. I imagined a child playing with their parent and how either player may or may not have the skill to guide the character, but may instead enjoy a more minimal but supportive role.

Long Pong, or Pooooong, was an attempt at re-imagining a classic game on the Cathode MK1. It was also an experiment to see how players would handle gameplay jumping rapidly from screen to screen. Long Pong also offered a competitive 1v1 experience which complimented the other two games which offered single player and co-operative gameplay.

Overall, the response has been very positive and equally diverse. Some are video artists who want to use the system for interactive, multi-channel video. Some are performance artists who want to incorporate it into performance space. And some are game devs who either want to design a game specific to this hardware or who want to retrofit an older project of theirs to work on the system.

When you start describing the limitations and the opportunities to them, their eyes grow wide with ideas. The problem is that most people don't have a pile of TVs kicking around to test their games on, nor do they have the additional converters, Arduino and multiplexer used to control the video output. In the future, I'm going to try and create a hardware package that developers can order and prototype with.

The big experiential difference I've observed is that people don't get 'sucked in' to the game. The physicality of the setup keeps the players firmly rooted in reality. Another aspect of this is the way players have to move their heads - not just their eyes - in order to follow the action of the game as it flows from screen to screen.

There's also a magical quality that players have a hard time articulating. It's something they've never seen before, but it seems so obvious and familiar, yet at the same time, impossible.

Each TV has a different response to losing video signal. Some display static, some show 'Video 1' and some just go dark. It's been fun to collect all sorts of old TV's that have their own personal quirks. Each one has a different personality. When I first presented the work, a lot of people thought that the games were going to be 'scary' because of the static and how quickly the screens flashed and changed, so I usually curate my collection of TVs to be ‘friendly’ looking whenever possible.

There are so many opportunities with experimental game interfaces and controls, but a primary focus of mine has always been accessibility. Current generation console controllers are a huge hindrance that most gamers probably don't think twice about. As someone who has gone to many festivals and events to showcase independent games, seeing non or casual gamers struggle with using an Xbox One or PS4 controller is something I consider anytime I sit down to design a game.

Ultimately, I want people to be able to experience the worlds and stories I craft without needing a Ph.D. in current gen controllers. As Michael Scott told Dwight: "K I S S. Keep it simple stupid." This is why I chose to use a USB NES controller for my Cathode MK1 games. I'm not saying that every game can get away with two buttons and a directional pad, but there's actually a TON of untapped design space within a limited control environment like that. Plus, players were able to quickly digest the controls and play through my games without issue, which is what we want as developers - for people to get into our worlds and play.

During the end of the project, the Xbox Adaptive Controller was announced, and it seemed to confirm that I was heading in the right direction by adopting minimal control schemes. This controller is one of the first steps in mainstream accessible gaming, and I think it needs to be celebrated and developed for. I'm hoping to save up and acquire a few of them to use with the Cathode MK1 for exhibitions.

You May Also Like