Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Octopad breaks an NES controller into eight game pads with a single input each, turning single-player games into multiplayer experiences built around communication and collaboration.

The 2019 Game Developers Conference will feature an exhibition called Alt.Ctrl.GDC dedicated to games that use alternative control schemes and interactions.

Gamasutra will be talking to the developers of each of the games that have been selected for the showcase.

Octopad breaks an NES controller into eight game pads with a single input each, turning single-player games into multiplayer experiences built around communication and collaboration.

Gamasutra had a chat with Patrick LeMieux, developer of Octopad, to talk about the unique play experiences that come from having eight players work together on a single-player game, how all of these players can reshape a game in exciting ways, and the varied personal play styles that come up when working together.

Hi there! I’m Patrick LeMieux, and I’m an assistant professor in the Cinema and Digital Media Department at University of California, Davis, where I teach game design, game studies, media theory, and media art. My academic research involves both writing about games as well as making games, and the Octopad is one of several projects I made after publishing Metagaming, a book co-authored with Stephanie Boluk about the games we play in, on, around, and through video games.

From ROMhacking and speedrunning to art-making and e-sports, Stephanie and I are interested in the strange things people do with video games and how the ways we play together can radically change the rules, mechanics, and even hardware of a given game. In Metagaming we argue that video games are not games but instruments, equipment, tools, and toys for making metagames, and the Octopad, for its part, is designed to turn old, single-player video games into multiplayer metagames.

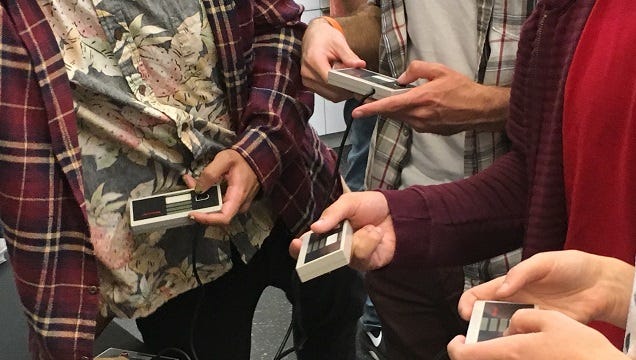

The Octopad is an alternative interface for the Nintendo Entertainment System that transforms classic titles like Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Tetris (or Yo! Noid, Gremlins 2, and Hatris) into cooperative puzzles and parties by dividing buttons up between four to eight people. To introduce players to the project, I usually hold up an unmodified NES controller in one hand and the snare of eight Octopad controllers in the other while asking “Instead of one controller with eight buttons, what if there were eight controllers with one button each? Instead of a single-player experience, what if Tetris was a team sport?”

Sometimes it takes a second, but when players realize that their controller has only the A button or a DOWN button (and nothing else!), they get the idea and start forming a team!

Despite playing, making, teaching, and thinking about games for a living, I actually don’t have formal training in programming or game design. My background is in architecture, media art practice, and media theory, so most of my experience with video game hardware and software is in the context of museums, gallery spaces, and research projects. Although I did make an episodic RPG Maker 2000 game throughout high school (the only game I’ve ever sold!), my game design experience comes mostly from a decade developing artworks and installations using tools like Flash, Max/MSP, Arduino, and Unity.

Some of the things I’ve made: a series of “art games” designed to be projected on monochromatic paintings at the MoMA, an iPhone app for virtually squatting an abandoned house during the US housing crisis (with Jack Stenner), an alternate reality game about the global economic downturn in the wake of the Occupy Movement (with N. Katherine Hayles and Patrick Jagoda), and a solo exhibition of weird Mario modifications (at Babycastles)—can be found in my portfolio.

Since Metagaming included a series of software demos designed to extend the arguments in each chapter, Stephanie and I have been making more video game-like video games. This year, we’ve been cleaning them up and posting them on Itch.io! For example, we recently released Footnotes, a 3D platformer featuring procedurally-generated pastel landscapes littered with hundreds of footnotes from the book, and Triforce, a short puzzle game that visualizes strange spaces from the original Legend of Zelda as donuts and spheres, Möbius strips and Klein bottles. The Octopad sits alongside this software as new, more game-like work being exhibited in festivals like ALT.CTRL.GDC.

The Octopad is a remarkably straightforward project. It’s an electrical and hardware mod, and I’m not actually using any software or fabrication tools like laser cutters or 3D printers to make it. It actually begins with a glut of NES controllers I buy on eBay. The controllers are tested and cleaned before I begin a full teardown. I unscrew them, remove face decals, take out the buttons and conductive pads, and desolder both the cord and 4021 bit-shift register. Once I have piles of empty shells, blank PCBs, desoldered microchips, untethered cords, and extra buttons I divide my time between resoldering the electronic components in a different order and modifying the face plates.

The cords are snipped and resoldered into the empty 4021 sockets corresponding with each different button. The faceplates are scanned, edited, printed, laminated, treated, cut out, and then stuck on original shells after they’ve been dremeled down and patched up (with hot glue!) After everything is fit back together the shape, weight, design, and texture all mimic the original controls. The verisimilitude of the controller is crucial for communicating to players how the Octopad works and how to play at first touch.

If anyone's curious, here's a video of the production process.

The Octopad was inspired by a treasure trove of photoshopped interfaces that Richard van Tol and Barrie Ellis posted on the Game Accessibility Forums over ten years ago. In their thread from 2006, you can see images of one-button Wiimotes and Atari Joysticks without sticks, Game Boys and Game Gears that start to look like smartphones, and even a lone DK Bongo and a Nintendo Zapper without a scope. Out of all the images, the original post of the NES controller with just a single A button struck me as both a clear critique of default or standard control schemes, and a really fun way to play together as a group.

The Octopad is an attempt to make that image playable and, following van Tol and Ellis, to reimagine a historic platform in the paradigm of one-switch games - games made by and for folks with limited manual dexterity that can be played with a single digital input. Rather than thinking about accessibility as a single-player problem, these controllers engage the social, political, and environmental aspects of video games to change the way we play.

Like Mary Flanagan’s [giantJoystick], the Octopad defamiliarizes the experience of playing video games by activating the space in front of the screen. It transforms the way we play by focusing on the metagame around a given game rather than just its mechanics, graphics, sound, and story. How should we play together? How should we communicate with one another? What words or gestures should we use and how should we position our bodies in space? What’s unique about playing with a particular group of people and how can we play well together?

Along the lines of Bernie DeKoven’s Well-Played Game, playing well together requires communication, caring, and collaboration (even in deeply competitive games) and I hope the Octopad activates these questions even within standard control schemes and single-player games.

Whether focusing solely on a single task or trying to coordinate more complex behaviors in a group, the Octopad highlights the tension between control as a private, personal, or individual phenomenon and control as a complex negotiation between bodies, technology, and culture. It’s alternate not only in the sense that it’s a custom or non-standardized controller, but also because it imagines alternate realities or alternate histories of control.

One of the reasons I research video games in the first place is precisely because they stage a conflict between the way we experience the world and the way technical media operate at speeds and scales outside the range of conscious experience. The Octopad intervenes by shifting the scales - splitting up and slowing down the NES’s operations and shifting what we mean by experience from something individual to something collective.

I didn’t have many preconceived notions about how people would play with the Octopad. Considering the work of modders and mappers, streamers and speedrunners, programmers and pro-gamers, play always seems to extend far beyond the intentions of game designers and boundaries of the game’s design. That said, I was really excited to see what would happen!

After being exhibited at the ALT.CTRL.PARTY at GDC 2018, the Octopad traveled around the world to games festivals like SAAM Arcade in DC, Different Games in Worcester, IndieCade in LA, Beta Public in London, and Video Games: Cohabitant in Shenzhen, as well as a bunch of meetups and conferences in Berkeley, Davis, Tahoe, Turin, and even Kuala Lumpur. In each place, people developed new ways to play together that went far beyond anything I could ever anticipate: new team structures and strategies, new code words and gestures, new approaches to old problems that are taken for granted when playing alone!

For example, before making the Octopad, I’d never seen people play Tetris by smearing fingers on the screen or shouting things like “Hard left!”, “On its back!”, “In the hole!”, and “Resting comfortably!” The way some players anthropomorphized the pieces to produce a shorthand for communicating group intent mirrored the types of strategies that emerge in local co-op games like Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes and Overcooked as well as online games like Counter-Strike and World of Warcraft.

Like most metagames, these forms of communication are not universal, default or standardized—they are personal, private, ephemeral, and represent the character of specific people, in a specific place, at a specific time. When Stephanie and I wrote Metagaming, these unique, local histories of play were what we found ourselves most captivated by, and these moments deeply influence how I think about game design.

At UC Davis, I teach a NESdev class where we mod controllers, learn a little assembly, and make new games for old consoles, so I’ve considered developing an original NES game for the Octopad that would make use of all the buttons (even START and SELECT!) Maybe some kind of fumblecore Voltron where START and SELECT pump the legs and UP, DOWN, LEFT, and RIGHT orient the body and A and B actuate arms would be fun? On the other hand, developing new software could obscure the way that the Octopad comments and critiques standard forms of control.

Like Farbs’ ROM CHECK FAIL, Rachel Simone Weil and Andy Reitano's Social Media Bros., or even TASVideo’s TASBot, the juxtaposition of retrogaming nostalgia with new contexts is crucial to how the Octopad operates. It’s not simply that the mechanics of retro games can be taken for granted allowing more bandwidth for playing together, but the memory of past plays deeply influences the metagame. In Tetris, experienced stackers might call the shots. In Zelda, only a few people might remember where the dungeons are located.

Rather than just communicating mechanical information like “press LEFT, press RIGHT,” players use the Octopad to teach each other how to play games like Mario Bros., Mega Man 2, Marble Madness, Mickey Mousecapade, or M.C. Kids.

At its core, the Octopad imagines a world where every video game is collaborative - where every game not only requires, but helps grow unique communities and cultures of play. And I think this aspiration is already at least partially true. Like in Sofia Foster-Dimino’s great comic, Single-Player as Local Co-op, taking turns or sharing a controller, watching someone play, creating a local tournament, making house rules, racing friends online, or modding software or hardware are all multiplayer metagames. Speedrunning doesn’t happen alone. E-sports don’t happen alone. ALT.CTRL doesn’t happen alone.

Multiplayer metagames are always occurring (even when you think they aren’t!), and the unique controllers exhibited each year at ALT.CTRL.GDC make it obvious that play itself is always irreducible, always custom, always alternate.

As for the Octopad, I’m really looking forward to exhibiting at GDC2019 and I’m curious to see if the Tetris high score will be beaten! Here’s the leaderboard so far:

11/19/18 Beta Public 80 Lines

10/13/18 IndieCade 75 Lines

07/22/18 SAAM Arcade 74 Lines

04/12/18 My Living Room 71 Lines

03/23/18 alt.ctrl.party 68 Lines

You May Also Like