Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

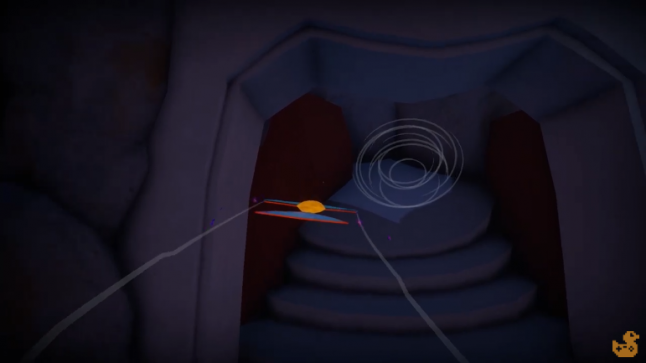

People of the Moon puts two players on teeter totters that guide a ship through the night sky, using both of their movements to capture the lights that glimmer in the dark.

Alt.Ctrl.GDC is dedicated to games that use alternative control schemes and interactions. Gamasutra will be talking to the developers of each of the games that have been selected for the showcase

People of the Moon puts two players on teeter totters that guide a ship through the night sky, using both of their movements to capture the lights that glimmer in the dark.

Gamasutra sat down with the game's developers to talk about what inspired them to create a game with a teeter totter, the nuances of building inputs using the playground toy, and the appeal of letting yourself play in a silly way as an adult.

Our team was comprised of Simon Giraud (Game Designer/Level Designer), Louis Le Gacq (Project Manager/Level Designer), Maëlle Fanget (Graphic Designer), Jérémy Guarober (Sound Designer), and Morgan Jobbins (Programmer).

Giraud: I started my studies with animation but, in my opinion, video game language has a big potential to send a message to the player through this interactivity. Practice is learning. And that’s beautiful. That’s why I’m now studying game design in CNAM-ENJMIN.

Fanget: I've always wanted to work in video games, especially on the Tomb Raider franchise, as when I was a child, my parents played it a lot. I've got an art degree in which I approached video games through the body/avatar perspective, although I've only worked only with Virtual Reality at the moment. I'm now in a masters degree at the CNAM-ENJMIN in Angoulême, France, specializing in game art.

Le Gacq: After 2 years working in the IT sector, I wanted to try to link passion and work. One year, I made a game jam game and I realized that video games is the field where I want to have a job. Now, I've spent a year and a half studying at the ENJMIN and working on several projects, and it’s very interesting. Video games are the best <3

Guarober: I worked for three years in audiovisual post-production as a sound assistant. I worked on many different projects such as TV fiction, ads, radio, movies, and the web. But, what I truly wanted was to work in the video game industry. I wanted to push my audio skills towards creativity - to develop immersive universes through interactive sound design and music. So, I joined the CNAM-ENJMIN where I’ve been studying for a year and a half.

Jobbins: Since I was around 10, I started making maps in various games, and then decided that I would make games one day. I went on to study computer science, orienting all my projects into gaming, and then went to the CNAM-ENJMIN, where I’ve been doing my masters degree in game programming.

We designed a cooperative game where you control a plane by using a teeter-totter. If you tilt to one side, then the plane tilts to the same side to turn. On top of this, each side of the teeter-totter has a lever to control the pitch of the plane, so both players coordinate their movement to properly control the plane. No pressure, no traps, just fun gliding in the air with your friend.

For the game itself, we used Unity as our game engine. We also used Maya, Substance Designer, Substance Painter, and Photoshop for the art part. For the sound design and the music, we used Wwise as our middleware and Reaper and Cubase for the sound design and composition.

For the teeter-totter, we got to learn how to properly do woodwork, learned to drill, measure etc… And got to meet the Great JPC. We used an arduino card to translate the teeter-totter’s movement into values for our game. To prototype, we used cardboard, paper, glue, and picked up stuff. Anything and everything that could

be useful.

We also used a car (a lot…) to go buy all of the teeter-totter materials. Special thanks to our car!

For physical materials, we used big wood planks and lots of screws. Then, to read the controls, we started by using distance sensors, and now are on gyroscopes. Also, we used some metal pieces to strengthen the structure and make something playable for people. We also used garden chairs that we cut to create two seats on each side of the teeter-totter.

For the levers, we first made it with a wooden stick, cut metal stick from caddies. and springs to add a return on the lever and give it a better game feel. However it was fragile. Now, we made some levers with metal door handles and plastic tubes. It was easier to build and the system is simpler and is stronger. Actually, levers are the part of the teeter-totter that we most iterated on.

Simon was drunk and thought it would be fun to play on a teeter-totter. He then thought making a game with it would be great, and the rest is history. It was so fun to play with a teeter-totter at midnight after a party with friends. We were drunk and stupid, playing with a seesaw in a park at Angoulême. The memories of this feeling are the base of the pitch.

We wanted a game where people could have a call back to their childhood, playing with their friends or strangers on a teeter-totter. Everyone knows what a teeter-totter is and how to use it; we all had fun doing so. This is a callback to those times. By using two levers to control the same part of the game, we force the players to communicate to play properly. This can either be an ice breaker, or just 10 minutes having fun and laughing like when we were children.

We had two main challenges, the first being: how do we place the players? On a normal teeter-totter, you’re facing one another, so if we want to make a game with it, either the players need to turn their heads for the whole experience or we put screens between them but they won’t see each other. We decided to try to turn the seats sideways. Now, they are facing a screen, and it is like if each player is on the end of a wing of the plane.

The second problem was how to control the pitch of the plane. We first thought of adding a second

axis of movement to the seesaw, but it would have probably been harder to control. We then opted for a lever on each side. This pushes the players to communicate together, and thus get a much more experience. Then, we had difficulties reading the teeter-totter’s movement to translate it into the game. After many iterations, we ended up with gyroscopes that work perfectly and give fluid controls.

Turning a teeter-totter into a controller was basically a challenge. It’s a big structure for kids and adults. It was very hard to build something like this, and it would not have been possible without help from Jean-Pierre Chastagnol and Tristan Lemaitre, and mostly the work of all the team. To be honest, we didn't have time to do playtests until the final presentation of the project. Even having the controller, we didn’t know if it was going to be fun and playable before the end.

As we had pretty difficult controls, we wanted loads of open areas, as well as some harder paths for players looking for challenges. The challenge was to imagine what it would be like to control this kite with a controller like this. We made some small prototypes with makey makey to get an idea of the game feel and navigation difficulty, but nothing was sure. These doubts explain why we definitely didn’t want to create a hard, challenging game, because, as a player, understanding the controls and synchronizing with each other is already enough of a challenge for a ten minute experience. So, we wanted to help players to make it easier, giving them wide spaces, forgiving rules, no deaths, and a navigational aid that enables players to move freely, avoiding the kind of frustrating situation where they would be stuck somewhere.

A second point was to create “key points” in the level design using the art and the sound to create some attractive places where the players would like to go. It’s a way to encourage players to communicate because they want to go somewhere on the map, but sometimes they don’t have the same desires. That’s why the cooperative aspect is important here.

As cited above, because of our controller scheme that requires coordination, players must communicate to play properly. They are also here for a fun time, as a game with a teeter-totter reminds us of our childhood days. The desire to understand and master the controller is the main point that makes sure strangers will cooperate. Maybe people forget where they are, they forget their shyness for a few minutes and they talk, move, and play with this controller, even if the situation is somewhat stupid when you take a step back. But that’s the good thing; you become innocent during that moment, like a child.

When working together in a game, players put aside their reality and unite in a new reality, which is how games break barriers down. Maybe don’t be afraid of making something “stupid”; have fun and enjoy childish games. Games can remind us, in certain ways, that we sometimes have irrational behaviors because we want to play. And it’s not a problem, because we are all just human.

You May Also Like