Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra chats with a few developers from different backgrounds who live with different chronic health conditions to talk about how it shapes their lives and life’s work in the game industry.

After a lengthy development cycle, indie team Heart Machine finally shipped the Kickstarted action-RPG Hyper Light Drifter (pictured) earlier this year, to critical acclaim and a measure of commercial success.

The game was delayed multiple times for reasons most devs know well: Heart Machine expanded the scope of the project when it raised more money than expected, and that led to a longer production cycle. Some things didn’t go as planned. The team just needed more time.

But there was another reason, one that Heart Machine made a notable point of talking about even though it’s rarely discussed in the game industry: chronic health issues. Project lead Alex Preston was born with a broken heart, and that shapes the way he lives and works.

You’re probably aware of that because Preston’s heart condition became a part of Hyper Light’s press coverage. It inspired the studio’s name, after all, and the tenor and tale of its debut game. Like most video game protagonists, Hyper Light’s titular Drifter is on a quest; unlike most heroes, the Drifter is afflicted by a mysterious chronic illness that frequently gets in the way of his work.

"There are very few jobs I could do comfortably, so being a game dev was something of a life-saver."

For Hyper Light players, the impact is meaningful but minimal. Occasionally the Drifter coughs up blood, or passes out and must be watched over by other characters. The illness only gets in the way when it’s convenient, or poetic.

For Preston, it’s not so simple. His heart condition, plus some extreme allergies and gastro-intestinal issues, are ever-present. They make it very hard for him to work long hours or travel very much, two mainstays of life as a modern indie dev.

“I was invited to speak in Japan - a place I dream of visiting - and I had to turn it down since I can't travel that long, to a place with food options that will be deadly for me,” he tells Gamasutra in a recent back-and-forth via email. “I also have a lot less energy than others, so I can't stay out incredibly late and hang out after a convention day, or even work days.”

Now that Hyper Light is out the door, it seems like a good time to talk about how chronic health conditions shape the lives of game developers, beyond the games they make.

It’s a topic too rarely covered; many people with chronic illnesses carve out careers for themselves in the game industry, often without talking about the process with their coworkers or fans in an effort to avoid appearing infirm.

That’s understandable, but it also makes it difficult for other people to learn from their experiences or find solace in their stories. So in an effort to shine a bit more light on the subject, Gamasutra recently got in touch with a few developers from different backgrounds who live with a variety of different chronic health conditions to talk about how it shapes their lives and life’s work.

As mentioned, Preston says he has a lot of difficulty traveling, has a lot less energy than most people and has to be very careful about what he eats -- so late-night work sessions, industry events and hangouts with other devs are tricky. Preston’s advice for fellow game devs facing similar challenges is simple: talk about it.

“Being open, transparent, about your situation and needs is paramount for survival and for the smoothest interactions,” he tells Gamasutra. “People will understand, if they are decent, and try and accommodate you if the need arises. Just talk and be willing to share!”

He also schedules his time so that he can work optimally for as long as possible, starting early (since he gets tired more easily in the afternoon) and taking small, frequent breaks or even whole days off if he feels his health getting shaky. The relative freedom to set his own hours as an indie dev is something he prizes, and he’s not alone.

“There are very few jobs I could do comfortably, so being a game dev was something of a life-saver,” says Olivia White, who serves as CEO and lead director at Owl Cave Games. “It means I can work from home, take care of my disability/pain levels when I need to, but still have a functioning career doing what I love. It’s lucky that one of the few options I have is also one I love so much.”

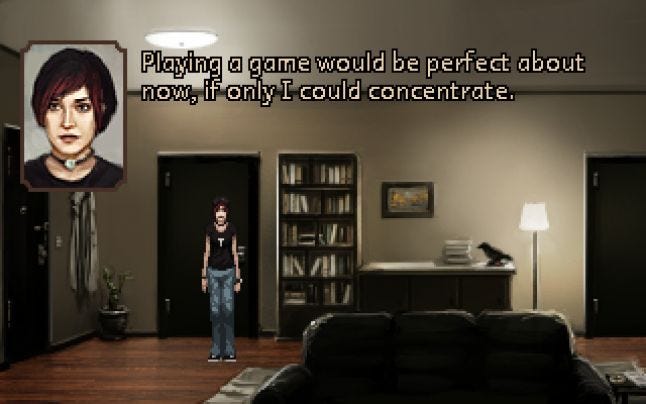

Owl Cave Games' Charnel House Trilogy

White says she lives with a number of chronic issues, including a significant spinal disability that “kicked in” when she was young and drove her to undergo corrective surgery, then another surgery to fix the correction. Now she lives with severe pain and mobility issues (which she wrote about earlier this year in a Polygon editorial) that keep her from either exercising too much or sitting for too long.

“Being able to take breaks and walk around whenever I need to is something I’m able to do as CEO of my own studio,” she says. “The major downside is that I can’t easily travel, or manage to attend events, and I know I miss out on a lot of networking and promotional opportunities by being restricted from attending things. It’d be nice if more game events had the opportunity for indies to show off their games without attending, or had better accessibility for devs with disabilities, but even then the pain that travelling causes me would still restrict me quite a bit. It’s the one area of my career where I know I’m held back by my disability, but it’s not too bad -- I still get a lot of opportunities through my job.”

Like many of the folks we chatted with, White says game development has some upsides for folks with chronic health issues. Hours are flexible, especially if you’re your own boss, and working remotely is an accepted practice. But there are significant downsides, too: beyond the afore-mentioned need to travel and network (especially if you’re indie), the work involves long hours in front of a computer screen and sometimes working in or for studios that lack accommodations for employees with health concerns.

“For a lot of disabilities, it can be quite hard for us to integrate and overcome things without employers doing more to raise disability awareness and accessibility, so I’d always encourage people to ask how they can make things better for their disabled employees or partners,” White says. “We really need the help and compassion of others to be able to do our jobs to the best of our ability; for me, it’s less of an issue being my own boss, but I’d always encourage people to think about this stuff.”

She also advises fellow devs to make self-care a priority, and to try and overcome any reticence or fear about asking their friends and coworkers for help.

“Never be afraid of asking for help. We deserve it; it’s not our fault that we need it,” she says. “Make sure to look after yourself and don’t push yourself too hard, make sure to remember you deserve good pain management and courtesy from others.”

"Crunch is a huge part of what made my disorder worse."

Self-care is something longtime game designer (and occasional Gamasutra contributor) Mike Stout has thought about a lot. His career spans time at Activision and Insomniac working on big-budget games in the Resistance and Ratchet & Clank series, as well as some indie excursions. Throughout it all he’s wrestled with severe panic attacks, symptoms of a panic disorder that developed after he’d entered the game industry.

“I didn't have my first panic attack until after I'd been making games for four years,” he tells Gamasutra. “It didn't snowball into a full-on panic disorder until many years later, but I have no doubt that my condition has been aggravated by my career choice.”

Stout says his panic attacks doubly impact his ability to work: in addition to making it difficult for him to talk with other people or engage with work at all during an attack, they cause crippling back pain thanks to fear-driven muscle tension.

He recalls that around 2010, after he’d taken a job at Activision, they started to happen with enough frequency and severity that he was forced to take four months off work to recover. He returned before he was ready for financial reasons, a decision he now says significantly aggravated his condition and led to him leaving the industry.

“In December of 2013, I completely collapsed and had to stop working on games entirely,” recounts Stout. “I started having panic attacks for 45 minutes out of every 60, which has gotten better over time. Nowadays I only have two or three a day. Since 2013 I’ve done some contracting, but I haven't worked full-time, and I'm not entirely sure I'll ever be able to work full-time again.”

As you might expect, Stout claims crunching on various games significantly exacerbated these health problems. He’s not alone, either; every developer consulted for this article said that crunch was as significant health hazard, and most said they’d had to work through damaging crunch periods.

“Crunch is a huge part of what made my disorder worse. Ratchets 1-3 were brutal crunches all,” he says. “On Resistance, I was under a lot of stress from other things and also crunching all the time. I started getting panic attacks that year, but they subsided after the project ended. “

However, he takes pains to point out that both Insomniac and Activision were decent places to work, in the context of the game industry at large. It was when he struck out on his own in 2013 as an indie dev that his illness really took a turn.

“I was a much worse boss to myself, and I worked myself constantly. I agreed to do too much, contract-wise, and was barely keeping my head above water,” says Stout. “By mid-January, I was having panic attacks for 45 minutes out of every hour. I had pretty much stopped seeing friends and family entirely. I couldn't take care of bills, or really do much of anything. When we called for help, and friends and family came, they found the house as a war-zone and found me shell-shocked and barely functioning.”

Stout says he’s in a better place now. He had to relearn how to continue a career in game development with a chronic condition, one that makes it very difficult for him to be available to other people and capable of working under stress for long periods of time when a project requires it.

He recommends other devs in similar situations be proactive about finding a medical professional who can treat their needs, and then also schedule time with a talk therapist who can help them learn coping strategies.

“I've learned how to ask for a break. How to stop conversations and resume them later. I've learned the warning signs that panic is coming on,” he says. “And when I notice them, I can take a break and use all the things I've been learning about how to take care of myself.”

Game designer and fellow former Insomniac staffer Lisa Brown (who also occasionally blogs on Gamasutra) ran into similar troubles when she struck out on her own as an indie dev, though for different reasons: she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia a decade ago, and has had to learn how to work as a game maker while dealing with chronic pain and fatigue.

“When I moved to LA for work, the mild, consistent weather and low job stress made it so that I was able to stop taking medicine and only had minor flare-ups now and again,” notes Brown. “I was able to participate a lot in industry stuff and it did not impact my work (though I did take naps in the afternoon from the fatigue a lot, but the studio had a nap room so it wasn't a big deal). If anything, needing to sleep way more often than average made me really efficient at work and good at predicting scope.”

But when she went indie in 2015 Brown, like Stout, ran into trouble.

“When I went indie, I was unprepared for the amount of stress I would suffer from the anxiety of the unknown,” she says. “For the last year I was the sickest I've ever been. I was in horrible pain most of the time and the fatigue was debilitating, and it created a sort of downward spiral.”

If there's one critical takeaway from these stories, it's this: There is no single foolproof way to survive and thrive as a game maker with chronic health issues.

Some folks, like Preston and White, seem to do very well as indies with the freedom to control their own environments, hours and workloads. Others, like Stout and Brown, find the stress and uncertainty of being out on their own (not to mention the lack of good institutional health insurance) untenable.

"It's still scary sometimes, honestly. Especially in an industry where it feels like so many successful, renowned games are pulled off by crunch cults, I wonder if I can even exist in this space."

Brown says that after a year of hustling to survive as an indie, she accepted a position at Harrisburg University as a game designer in residence, in large part because it afforded her “REALLY good” health insurance and gave her a reprieve from the stress.

“I learned a lot over the past year of having to accept and yield to my condition when it becomes a problem. I kept trying to fight it, and push through it, and I just overworked myself to the point that my body shut me down,” says Brown. “Since moving back to a place with weather [Harrisburg is in Pennsylvania, which has four seasons to L.A.’s one], I managed to find a good doctor and get back on some medicine to manage the pain again. It's not really fixing the problem, just lessening the severity of the symptoms. I still deal with the fatigue, though, and am much more cautious about listening to my body.”

Both Stout and Brown recommend fellow devs in similar situations find a doctor they can trust and feel comfortable talking with, one who will work with them to try and find solutions that don’t just treat their symptoms, but improve their quality of life.

They also each champion the value of having a trusted support network of friends and loved ones, people you can turn to to talk about these problems.

“Things move so fast in the games industry, it’s easy to feel like ‘How can I even be here?’” says Brown. “‘Even most normal people can't keep up and I have all these other obstacles to overcome and can't work at the same pace, how can I make it in this industry?’ In these moments, having the reassurance and support of others in the industry has been a huge help.”

It’s also important not to tie your work to the value you see in yourself. Brown says she struggled -- still struggles -- with stress that she “had no worth because I couldn’t work”, but now she’s come to understand that it’s a false equivalency which only made things worse.

“It's still scary sometimes, honestly. Especially in an industry where it feels like so many successful, renowned games are pulled off by crunch cults, I wonder if I can even exist in this space,” she says. “But you can, you just have to figure out where you can fit, and having industry support in those times is really important.”

To get that support, Brown suggests developers who struggle with chronic health issues share their stories. With family and friends, coworkers, and the industry at large.

“I used to be really closed off about talking about my fibromyalgia, because I feared it would come off as complaining or trying to get attention or pity,” she says. But with encouragement from friends she started talking more openly about it.

“Almost every time I've had someone else message me and thank me for it, usually someone else suffering from a similar condition telling me how it made them feel less alone,” Brown says. “I think if you can help even just one person feel less alone by sharing your story, it's so worth it.”

You May Also Like