Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Consider a 2D world with polygonal buildings; the edges of the polygon be building walls. Given a viewer/agent who's indoor or outdoor, we try to draw the area "seen" by the viewer; this the player can use to make strategies before making a move.

A common requirement in strategy games is to know the area looked-at by an NPC for the player to strategize and make her next move. We get to the math and implementation of how to do this efficiently so that the game's frame rate wouldn't plummet when there are lot of agents strewn across the map. If you wish to see a finished, interactive demo of this, head here to play with it directly from your browser! Here is a screen grab:

Given the observer's vision parameters — viewing direction, vision distance or the reach of sight and the angle of vision — we have to find the region visible to the observer i.e. the field of view (FoV) is to be determined. With no obstacles it would be a sector, made of two edges (radii) and a connecting arc; see figure 1. Additionally, given a point in the world, we should be able to quickly tell if this point is visible to the observer i.e. line of sight (LOS) queries on a given point should be serviced. Both these operations should be performed in a way efficient enough to use it in real-time rendering scenarios.

Figure 1

The observer's position is shown as the red dot, the arrow points to the viewing direction, r denotes vision distance and θ is half the angle of view.

Set of polygons; includes the world boundary

FoV Parameters

Position of viewer

Viewing direction, V

Angle of vision, 2θ < 180°

Vision distance, r

Note: The convention used through out is lower case letters for scalars and uppercase letters for vector values.

When describing a world in 2D, buildings naturally map to polygons and are thus taken as input by the algorithm. However, technically vision is blocked by walls i.e. polygon edges; moreover, dealing with polygon edges gives greater granularity and better control as we will mostly be dealing with geometric primitives when performing intersection testing. Hence, for the most part, the algorithm considers edges directly without worrying about the higher-level abstraction, polygon.

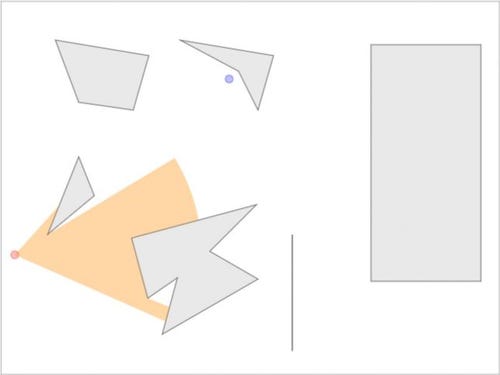

An interesting initial idea that occurs is clipping the vision sector with the polygon paths. However, this is a vision problem, and trying to solve it with path clipping will not work; we will just end up with an incorrect result. This is understandable as clipping just cuts away the intersection of two regions, while for vision we need to cut not just the intersection, but everything behind it; also this is to be done radially. Figure 2 shows the result of clipping (left) along with the expected result for this configuration (right).

Figure 2

In the physical world, we see things when unhindered light rays reach the eye. Intuitively, vision can be determined by doing the converse i.e. casting rays from the eye into the world. For a light source, the rays emanating from it would go in all directions. When implementing it, rays are shot at some regular interval radially e.g. a ray every 5° would mean shooting 72 rays for full circle coverage. The ray is assumed to go on until it is blocked by an edge. Shooting rays in all 360° and finding the reach of a light source in 2D is a solved problem [1]. The accuracy of this method depends on the interval at which rays are shot; smaller interval gives denser ray distribution.

Figure 3

Shooting rays is a fancy way of saying testing for ray – line segment intersection. For a given ray, if there are m segments, m tests are done to find the edge closest to the ray that blocks it. So for any ray casting algorithm, to shoot n rays, on a set of m edges, n × m tests are to be performed. However cheap the ray – line segment (edge) intersection testing may be, for a huge world with many lights this may become prohibitively expensive.

Let us call the edge that blocks a ray as the blocking edge. Figure 3 highlights them in red. The point where the ray hits the blocking edge would be the hit point. Once all hit points are found, they should be connected circularly i.e. all hit points are sorted by angle, and connected by lines to get the region lit by the light source. The result is essentially an irregular, closed path. Note that when connecting hit points in this fashion, some corners or parts of the polygons are chopped off, leading to an incorrect or less accurate light field. This can be improved by decreasing the interval at which rays are shot; lesser interval means more rays, greater coverage, better output at the cost of performance.

We have discussed, with the help of this light reach problem, the basic approach we will take to solve our problem: ray casting. Note that the light rays originating from the source travel in all directions and with no limit in distance until it hits an obstacle. Having no limits makes it a simpler problem compared to the one in hand where both angle and distance of vision are bounded. We will discuss why it is so later in §3.

Instead of shooting rays in all directions (at some interval), a common optimisation is to shoot rays only in the directions where edge endpoints are present. This should drastically reduce the number of intersection tests required; the aforementioned n term should become smaller. An additional advantage of this method is greater accuracy; we are no longer at the mercy of the interval chosen for the field of view to be correct.

Figure 4

We will call these edge endpoints, which gives the angle to shoot rays at, as angle points. This term might seem redundant and pointless as a substitute to endpoints, but it will have its use down the line. Angle points are points at which rays of sight are shot. In figure 4, angle points are shown in red, blue and black; rays are shot at all of them. Those that lay closest to their ray got converted to hit points, shown in red. Those to which their ray never reached are in black; these rays hit a more closer lying blocking edge and created hit points; these are shown in blue.

Though shooting rays only to edge endpoints would do, there is a small wrinkle to iron out. In figure 4, note that the ray shot to a polygon's corner hits one of the edges that form the corner and does not proceed further. However, vision should extend beyond the corner in some cases. A clever way to correct this problem is demonstrated with an interactive article by [2].

The idea is make two auxiliary rays by tilting the primary ray — the ray to the edge's endpoint — by an iota angle both clockwise and counter-clockwise. If vision has to extend beyond a corner, one of these auxiliary rays would get past the corner thereby deducing visibility beyond. The downside is for every angle point, we now have to shoot three rays, not one, from the observer; this triples our expenses. It would be good if we could minimize the number of angle points we need to process.

Figure 5

Auxiliary rays of a primary are shown in orange; the angle of tilt (between an orange and black ray) is exaggerated here for clarity, but it would me much smaller, say, half a degree.

An easy optimisation would be to find if both edges forming the corner are exposed or one of them is hidden by the other. If both are visible then no auxiliary rays are needed since vision cannot extend beyond; in figure 4, the apex of the triangle is an exposed corner; auxiliary rays are redundant here as vision cannot be extending beyond. Auxiliary rays are needed only if one of the two edges is hidden to the viewer; both cannot be hidden since we are looking at every corner of a polygon in isolation — two edges and the point they meet (figure 6, black arrows and blue dot). Even when one of the edges is hidden, sending two auxiliary rays is redundant; one can be avoided as only one will go unblocked beyond the corner. In figure 5, the auxiliary ray formed by rotating the primary clockwise is redundant.

Figure 6

Separating axis theorem can be applied to find if one of the edges of the corner block another. Projecting both edge vectors on to the vector perpendicular to the primary ray would give results with differing signs if one of the edges block the other. Also depending on the sign of projection of the first edge, we can know which of the two auxiliary rays is needed. In figure 6, the three possible situations are shown at the top and the projection results are show at the bottom; the black dot denotes the viewer position from where the primary ray (red) is shot. The edge vectors (black) are projected on to the primary perpendicular vector (green). When no auxiliary rays are needed, both projections give negative values, since both edge vectors are in the negative half-space of the perpendicular. In the remaining two cases, where auxiliaries (orange) are needed, the signs of the projection are different for the vectors; when the sign is negative for the longer edge vector, a clockwise rotated auxiliary ray is enough and when it is positive, a counter-clockwise rotated auxiliary ray is will do.

For the problem considered here, vision is bounded in angle and distance; this leads us to interesting situations.

Not all endpoints become angle points; only the ones within the view sector count.

This should at least halve the number of rays shot; n should become even lesser now.

To reap this benefit, effort needs to be spent in filtering angle points from endpoints. The technique used to prune should be quick so that filtering itself does not take too much time.

Likewise, most edges will not be potentially blocking; just the ones which are contained or cut by the sector matter.

This will reduce the number of intersection tests needed; the m term should become lesser.

For this too the onus of quickly rejecting edges that do not count is on us.

A prime difference or deviation from the basic algorithm explained in §2 is that there can be angle points that do not come from the set of edge endpoints. There may be more angle points needed to be found. Consider the configurations shown in figure 7 and 8. The edge endpoints are outside the vision sector, and thus are not useful as angle points. All angle points needed to correctly determine the field of view (shown in black, blue and red) do not come from edge endpoints. Every one of these are necessary; failing to shoot a ray at any of them would lead to an incorrect determination of the visible region. How are they different and how do we find them?

Since vision is bounded by the viewing angle, two angle points are essential and are to be taken implicitly irrespective of the presence of an edge. They come from the far endpoints of the sector's edges. Rays are shot at them and hit points are determined. Figure 7 shows one of these implicit angle points in black; the angle point due to the sector's right edge endpoint. The ray shot to it is blocked by an edge, leading to the blue hit point. Another ray shot to the angle point due to the sector's left edge endpoint is unhindered and thus the angle point itself becomes the hit point, shown in blue. So the blue ones are easy to determine; they need no tests. Their position is fixed, relative to the vision sector's position and orientation.

Consider the red angle point (turned into a hit point since the ray is unhindered) at the intersection of the sector's arc and the edge. This one needs another intersection testing: arc – line segment intersection test. These angle points are needed when an edge intersects the sector's arc.

Figure 7

Ray is shown with an arrow head while the edge has endpoints.

Figure 8

With these considerations, we list the cases where angle points occur:

Any edge endpoint contained by the vision sector

Any point on the sector's arc where an edge intersects it

Likewise, potentially blocking edges are the ones fully or partially contained by the sector.

The problem now becomes that of compiling the set of angle points (finding new ones and filtering unnecessary endpoints) and the set of potentially blocking edges (pruning surely non-blocking edges). This should be done fast, rejecting invalid elements as early as possible, so that cycles are not wasted in processing something whose result will ultimately be discarded. The aim is to reduce the terms n (number of rays shot = count of angle point) and m (number of line segments to test the ray against = count of potential blocking edges), giving us a fast algorithm to determine the FoV.

[3] suggests that an ideal culling algorithm (in reality, costly and riddled with floating-point precision problems) would only allow the exact visible set, while a good one would reject most invisible cases accepting the definitely and possibly visible ones. It will be conservative about rejecting potentially visible ones. In other words, unless it cannot be absolutely sure that an edge would not hamper visibility, it does not reject it.

A naïve idea to reject irrelevant endpoints and edges would be to only test if the edge's endpoints are within the sector; this would work for angle points but is insufficient for blocking edges, as it would fail in configurations where the edge endpoints are out but the edge blocks visibility; see figure 7 and 8. Before going to the more granular entity, the endpoints, if we can reject the edge, the endpoints testing can be skipped altogether.

If a line segment's closest point to the circle centre is within the circle then it is either contained by it or they intersect. This idea is detailed here [4]. Using this with the edge and the sector's bounding circle, we can reject all edges that are disjoint from the bounding circle. Post this stage, all edges that have nothing to do with this circle are not considered. Since this is not a test to find the actual points of intersection but to just know whether the edge is disjoint, the result is boolean and is fairly fast. All we need to implement this test is a couple of vector subtractions (making the vector) and dot products: one to find the closest point (by projection) and another to compute the squared distance to the circle's centre from there.

Results of this test is shown in figure 9. The vision sector's bounding circle is drawn with dashes. The blue dot on every edge denotes its closest point to the circle's centre. The green edges are accepted; the magenta ones are accepted too but are false positives. The red ones are rejected. An edge that is tangential to the bounding circle is rejected as well since it will not occlude vision.

Figure 9

To reject false positives aggressively, the idea of testing if the closest point is within the sector, as opposed to the circle, is charming. However, this is incorrect as it will also reject positives; in figure 9, along with the magenta ones, the green edge having its closest point outside the sector would also be rejected.

Given a point and a sector, it is easy to quickly determine if the point is

behind the viewer

in front of the viewer and

beyond the viewing distance

within viewing distance and

within the sector

outside the sector but inside its bounding semicircle

with just dot and cross products. Since cross product is not defined in 2D, we promote our vectors to 3D by letting z be 0. Though cross product results in a vector, as z = 0, elements pertaining to x and y would be 0, and only the z quantity will be non-zero (if the vectors are not parallel); thus we get a scalar result from this cross product; refer [5] for different definitions of cross product in 2D.

Let the vector from the circle centre to the point be (U) and the sector's edge vectors be E1, E2. We already have the viewing direction, V.

If U ⋅ V < 0, the point is behind the viewer.

else if U ⋅ U = ‖U‖2 > r2, the point is beyond viewing distance.

else if sign(E1 × U) = sign(U × E2) then the point is within the sector.

else it is in the bounding semicircle but outside the sector.

We have used two optimisations that need explanation. We compare squares of the lengths (2) instead of just the lengths since finding the length would mean using sqrt; we avoid this and do an optimisation that is usual in computer graphics applications [7]. To check if the point is within the sector (3), we could have found the actual angle it subtends with the sector's first edge and see if it is within the allowed angle of view (2θ). However, we need the trigonometry function acos for this, which may be a costlier than doing a couple of cross products which involves only arithmetic operations.

If an edge survived through the previous test, we put its endpoints through this test to classify where they stand. Figure 10 shows how the situation is now; the grey points are behind (1), red ones are beyond (2), green endpoints are within the sector (3) and the magenta one is in the bounding semicircle but outside the sector (4).

Figure 10

Angle points and blocking edges can be determined based on the results

If both ends are behind (1), it has no way of obscuring vision; prune — stop further processing.

If both ends are within the sector (3), mark both as angle points and the edge as blocking; stop further processing.

If one of them is within the sector (3) and the other is not — (1), (2), (4) — mark the one within as angle point and the edge as blocking. This edge may cut the sector's arc and give a new angle point.

If both are not within the sector — (2), (4) — endpoints are not angle points, but it may cut the sector's arc, giving new angle points. Edge may be blocking if it cuts the sector's arc or edges.

For cases 3 and 4, we need further tests to find angle points, that are not endpoints, the edge contains and whether the edge is blocking. This leads us to the narrow phase of culling.

In this phase we weed out more false positives with costlier tests to improve performance when shooting rays. We may perform an edge – sector arc and/or an edge – edge intersection test.

However, before performing the slightly costly segment – arc intersection test (it has a square root and more than three branch operations), we can use the results of the previous test to see if the test is really needed. The test is needed only when the edge has a possibility of intersecting the arc. If both the endpoints are within the sector's bounding circle, the edge has no way of intersecting the circle; the edge has a possibility of intersecting the sector's arc only if either of its endpoints are in front of the viewer and outside the bounding circle (case 2.a in §3.1.1.2).

Table 1.Edge endpoint possibilities and states

# | End A | End B | State |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Within | Within (2.b.i) | Angle points: A, B • Blocking |

2 | Within | Behind (1) | Angle point: A • Blocking |

3 | Within | Semicircle (2.b.ii) | Angle point: A • Blocking |

4 | Within | Outside (2.a) | Angle point: A • Blocking • May intersect arc |

5 | Behind | Behind | Prune |

6 | Behind | Outside | May intersect arc • May be blocking |

7 | Behind | Semicircle | May be blocking |

8 | Semicircle | Semicircle | May be blocking |

9 | Semicircle | Outside | May intersect arc • May be blocking |

10 | Outside | Outside | May intersect arc • May be blocking |

Items 1, 2, 3 and 5 are already dealt with in the broad phase and needs nothing further. Item 4 needs an edge – arc intersection test just to know if there is an additional angle point; already in the broad phase we marked one of its endpoints as angle point and the edge as blocking. Items 6 to 10 are of the most interest in the narrow phase. Items 6, 9 and 10 need edge – arc intersection testing to know if any angle points are present due to the intersection, and if so, the edge should be marked blocking. If these items fail in the test, they join items 7 and 8; all of these cannot be having any angle points, but should still be put through edge – edge intersection test to know if they are blocking.

For items 4, 6, 9 and 10 in table 1 we check if the edge cuts the sector's arc with a line segment – arc intersection test [6]. If it does, mark the intersection point(s) as angle point(s) and the edge as blocking. No further processing is needed. If it does not, the edge cannot be having any angle point but pass the edge to the next test to know if it is blocking.

The test is essentially a line – circle intersection test and hence would result in two points. The points that lie on both the line segment and the arc are deemed points of intersection. A minor optimisation that can be done here is if both points of intersection are behind the viewer then the line segment cannot be blocking or having any angle point, hence the edge can be discarded without any further processing.

Figure 11

In figure 11, the grey edge with an endpoint outside and another behind is tested but both intersection points are behind (magenta) and is thus rejected. The green edge with both points in the semicircle is never tested. The red one with one of its endpoints outside is tested but the only intersection point found (blue) is not on the arc; this edge cannot be having any angle points but is sent to the next stage (edge – edge test) to test if it is blocking. All other edges (black) with one or both its endpoints outside the bounding circle and having valid (red) intersection point(s) are marked blocking, with the intersection points marked as angle points; each such edge corresponds to one of items 4, 6, 9 and 10 in table 1.

For items 7 and 8 which never entered the previous test and for items (6, 9 and 10) which entered but no intersection points were found, there can be no angle points the edge bears: both its endpoints are not within the sector and no new angle point is lying on the arc. However, such edges cannot be discarded as they may still be blocking (see figure 8) or unblocking (see figure 10; the edge with magenta endpoint). We have two options: be on the safer side and mark them blocking or test them against the sector's edges to be sure. By doing the former, for every false positive edge — an edge disjoint from the vision sector — we pay with n line segment – line segment tests during the ray shooting phase, as every ray shot should be tested against every potentially blocking edge. Instead of paying n times for a false positive, paying n + 2 (at worst) for a positive is a better proposition, so we test the edge against both the sector edges; if it intersects any, mark it blocking.

Figure 12

For items 6 to 10, figure 12 contains two edges each: one positive (green), one negative (red). From the figure it is apparent that this test has greater chances of rejecting edges irrelevant to vision.

We have all the angle points and blocking edges. Before casting rays, the angle points are to be sorted by angle so that the final field of view figure appears correctly when the hit points are connected by edges and arcs. Additionally, if two or more angle points and the viewer position are collinear, then multiple rays will be shot in the same direction; duplicate angle points need to be discarded to avoid redundant rays.

For the sorting, the technique explained in §3.1.1.2 of using the cross product to find if a point is within the viewing sector angle can be used. Duplicate angle points can be dealt with easily again with cross product. For every angle point, before casting the ray, it is crossed with the previous ray, if the result is zero then the vectors are linearly-dependant (parallel) and thus can be ignored.

Primary rays are shot at the sorted angle points. Before shooting a ray at an angle point, if we know it is an edge endpoint, and not an intersection point, then auxiliary rays are to be shot as needed; refer §2.2 for details on this. Auxiliary rays are to be shot only for angle points that are edge endpoints and not for the ones from intersection points, as the latter cannot be polygon corners, so vision should not be extending beyond.

For every ray shot, we find the intersection point of the ray and the edge closest to it. This is the hit point for the ray. If this point lies beyond the vision distance, r, then we take the hit point as the point along the ray that is r units away from the viewer i.e. we drag the hit point back until the distance to it from the viewer becomes r. For every hit point found, we check if it is at the arc boundary, if this and the previous point are at the arc boundary, then we connect them both with an arc else with a line. However, there is a small problem in doing this blindly.

Figure 13

In figure 13, the hit points (numbering from right to left) 1 and 2 are on the arc, they should be connected by an arc. Same is the case with hit points 3 and 4. However, hit point 2 and 3 should be connected by a line since there is an edge cutting the arc. When hit point 3 is found and confirmed that this and the previous hit point are on the arc, check, before connecting them with an arc, whether the line connecting them is parallel to the closest edge on which hit point 3 lies; connect them with a line if it is parallel.

A line of sight query is to answer the question of whether a given point, X, within the world, is visible to a viewer, with the viewer's parameters defined (§1). Doing this is easy once the blocking edges and angle points are found. First we classify X according to §3.1.1.2. If it's not within the sector, we return false. If it is within, we check if the line segment formed by connecting X to the viewer is intersecting any of the blocking edges. If it is not intersecting, we return true, since the line of sight or the ray from the viewer to the subject is unblocked and is thus visible.

2D Visibility by Amit Patel

Sight & Light by Nicky Case

§14.2 Culling Techniques, Real-Time Rendering, Third Edition by Thomas Akenine-Möller, Eric Haines and Naty Hoffman

Line segment to circle collision/intersection detection by David Stygstra

§A.2.1, 3-D Computer Graphics by Samuel R. Buss

Intersection of Linear and Circular Components in 2D by David Eberly

§2.2.5, Essential Mathematics for Games and Interactive Applications, Second Edition by James Van Verth and Lars M. Bishop

3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development, Second Edition by Fletcher Dunn and Ian Parberry

Mathematics for 3D Game Programming and Computer Graphics, Third Edition by Eric Lengyel

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like