Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A technical overview on the use of metrics for BloodRayne: Betrayal, the upcoming hack-n-slash title for PSN/XBLA.

I spent the last six months working with my good friends at WayForward on the upcoming 360/PS3 downloadable title BloodRayne: Betrayal. BloodRayne is WayForward's somewhat-ballyhooed first attempt at an HD console game, and as such, there's probably a lot of interesting technical remarks to be made about our frequent missteps, and occasional successes, along the gory path to its completion.

But for various NDA- and time-related constraints, this entry will stick to a somewhat peripheral subject: the use of game-generated, server-tracked statistics to supplement the development process.

The shorthand terminology I'll use for this topic is metrics, which for most game industry establishment-types tends to conjure images of the back room at Zynga, where cackling MBAs with protractors and slide-rules measure the exact point where the dilation of one's game-addled pupils goes from signifying Mind-Numbing Tedium to Big-Time Profits.

This being a technical discussion, I'll elect to sidestep the precarious, albeit interesting, debate over the aesthetic and spiritual merits of metrics-driven game design. Suffice it to say that BloodRayne, very much a product of an old-school design and development process, benefitted greatly from a very moderate application of metrics, and could have used even more had we had the time and wherewithal.

The imaginary ideal, as proffered by our illustrious lead programmer, was to produce a "heat map" system that would enable us to overlay our gameplay worlds with a dense mass of visually-rendered statistical data, which would in turn allow us to tell at a glance how quickly testers were progressing through our levels, where they were most likely to die, which moves they were using to deal the most damage, and so on and so forth. Unfortunately, the inspiration for this system hit us with roughly two months left on the schedule, and with a fair amount of feature implementation still on the docket, we were forced to settle for something much more modest. What we ended up with was still very important to tuning the game's scoring system, and played a surprisingly useful role in the debugging process.

The technical scheme we came up with for BloodRayne's metrics system was nothing particularly fancy: we'd a) send JSON-encoded data in the body of an HTTP POST request to our in-office web server, which would b) invoke a PHP script that threw all of the incoming data into MySQL, and then we'd c) write one-off scripts to collate and present the data as we needed them.

We decided fairly early on that the data produced by the game would determine the database schema. In other words, we did not define our SQL tables in advance. Instead, we let the gameplay code generate data in the form of arbitrary key-value pairs, and made sure the server script was smart enough to create tables or modify pre-existing tables when necessary.

Having been weaned on certain data design paradigms that preach the sacredness and run-time inviolability of one's table schema, I at first found such cavalier treatment of the database to be sort of gross and philosophically outrageous. But it did turn out to be the fastest way to churn out lots of data, since it relieved us of the duty of preparing the schema before we started pumping statistics into the database. With the table schema defined implicitly by whatever was in our gameplay code, our only real responsibility was to make sure that we were type-consistent about the values we were sending to the database; e.g., if the health field was initially sent as a floating point value, we needed make sure it wasn't later sent as a boolean.

Our JSON encoding of a row of data was about as concise as is theoretically possible, and looked something like this:

[

"tableName",

[

[ "field1", "type", "value" ],

[ "field2", "type", "value" ],

...

]

]

Here, the types of each field were single-letter strings, indicating your usual data primitives: integers, unsigned integers, floating point numbers, booleans, and strings. Specifying the type allowed us to generate new table columns if necessary, and to type-check against pre-existing columns as well. The values for each field were encoded as strings, produced by running plain old C data through sprintf(). In order to keep string length down, we didn't bother to use JSON objects with named properties--we just stuck with arrays and inferred the role of each string token based on its context.

The C++ API for this system was also designed to be as simple as possible, so that gameplay programmers could instrument their code with just a few calls to the metrics library and see immediate results in the server. We wanted the code to be no more complicated than the following example:

void RecordLevelEndData()

{

// Grab in-game data

float fHealth = GetPlayerHealth();

unsigned nScore = GetPlayerScore();

// Get an object that sends data to the

// "performance" table

wfStat* pStat = wfMetrics::Create( "performance" );

// Add field data, using handy overloaded methods

pStat->AddField( "health", fHealth );

pStat->AddField( "score", nScore );

// Queue the data for upload.

// To prevent network overhead from interfering

// with the gameplay thread, a separate thread

// will handle JSON encoding and HTTP

// transmission.

wfMetrics::Commit( pStat );

}

We used a variety of tricks to make this as fire-and-forget as possible. We made sure that gameplay programmers didn't have to worry about cleaning up any allocations that the metrics API might have made, and also designed the API so that metrics code could be safely embedded in gameplay code even if the metrics system had been disabled or compiled out of the build.

As a final expedient, we made it so that gameplay programmers could specify project-specific metadata that would be included into every row of data sent to the server. This included fields that would describe the source of the data, such as the revision number of the executable, and the timestamp corresponding to the moment that the data was inserted. So the actual JSON data sent from the above sample would look something like this:

[

"performance",

[

// Project-specific metadata

[ "svn_revision", "s", "195388" ],

[ "platform", "s", "ps3" ],

[ "system_id", "s", "08EB4EEF3C76C468" ],

[ "timestamp", "d", "__server_timestamp__" ],

// Programmer-specified data

[ "health", "f", "6.9999999e-1" ],

[ "score", "u", "323450" ]

]

]

It's amusing to recall that despite all the effort put into making this system as generic and flexible as possible, we were still too lazy to implement DNS support in our network wrapper functions. We just left the IP address of our local database server hardcoded into the source.

Our first application of this metrics system was to collect information about player performance. BloodRayne consists of several five- to ten-minute levels, each broken down into platforming sections and intermittent "screen-lock" battles, in which all enemies must be defeated before the player can progress. At the end of each level and screen-lock battle, we fired a slew of performance statistics at the database server: the time relative to the start of the level, the amount of health lost by the player up to that point, the number of points accrued from defeating enemies, the specific means by which an enemy was killed, etc. etc.

This data enabled us to answer questions of a very specific nature, such as "For level X, given the player's accumulated score, what canonical letter ranking (i.e., F, C, B, A, or S) should we award?" It also gave us a fair amount of insight into which levels and which battles were too long or too difficult.

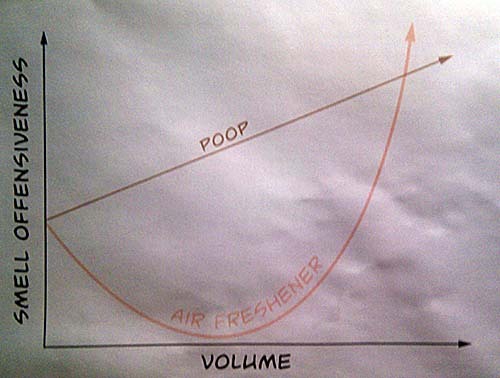

The process of analyzing this data was, as with much that goes on behind the scenes in game development, decidedly unsexy. Rather than writing a script to iterate through the data and present statistical summaries, the programming staff elected instead to deploy the tried-and-true Browse The Raw Data Directly strategy. Pleading overwork, we swiftly passed the buck around the cubicles, until it devolved to our harried and unsuspecting designer-director, who was deemed more than fit for the task after he produced this fine piece of analytical demagoguery concerning the overdeployment of air freshener in the WayForward bathrooms:

Eyeballing data in phpMyAdmin may seem to be, in the parlance of our times, a ghetto tactic, but it works surprisingly well for producing ballpark estimates and alternatively supporting or refuting one's hunches about the quality of the game's play-balancing. We spent a lot of time trying to see what peak gameplay performance looked like from a numerical perspective, and in many of these instances, we could simply have a designer or an expert tester play through a level and then immediately load up the raw data to take notes.

The conversation about game statistics had always been framed in terms of measuring some kind of player behavior, but we eventually ended up using metrics to great success for debugging under-the-hood systems such as dynamic memory allocation.

BloodRayne splits its memory allocation into several system-specific heaps. A simple technique for making sure you aren't leaking memory is to record the allocation size of a heap, perform allocations and deallocations, and then re-sample the heap's allocation size to verify that it is the same as your initial sample. But for various structural reasons, it wasn't easy to come up with a consistent method of performing checkpoint operations on our heaps. Some subsystems made allocations that were meant to survive in perpetuity, making it hard to know what allocation values to verify against. On top of this, not all subsystems performed deallocations during the same moment in the game flow, so it was difficult to find a single, general spot to situate our checkpoints.

However, one thing we could do was plot heap allocations over time, and see if there were any patterns--in particular, an upward trend in allocation size would strongly imply a memory leak. So we hooked up our metrics system to broadcast the allocation state of each heap at transitional moments in the game flow, mostly when the player progressed from one game level to the next. We could gather this data from our testers without interrupting their playthroughs, and since we had data from multiple sources, we could get a rough idea of how consistent our memory leaks were.

Since it fell on me investigate most of our memory leaks, I afforded myself the extravagant luxury of creating a visualizer script for our heap allocation data. I promised my colleagues in no uncertain terms that it would be a cold day in hell before I would be railroaded into squinting at thousands of rows of data from phpMyAdmin. After all, what was I, a peasant?

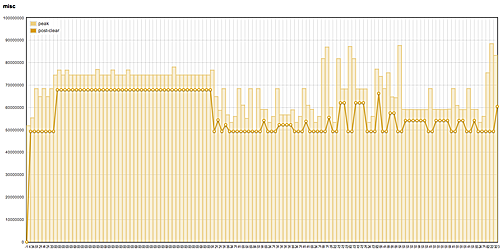

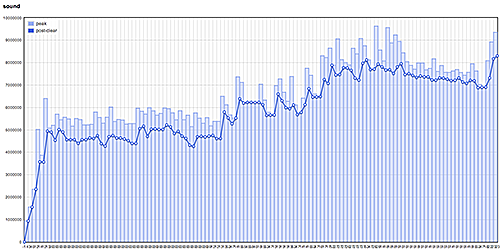

A search for "javascript plotting" led me immediately to flot, a relatively simple graphing library that produced unambiguously pimp-looking results. A few days of fiddling resulted in graphs such as the following:

Above, we see a graph of 123 allocation samples, constituting about an hour or two of gameplay, to the misc heap, which is BloodRayne's primary heap for game object allocations. The allocations here are considered well-behaved, in that there is no identifiable upward trend in their size. Any sustained peaks in the allocation pattern are due to level reloads (almost always attributable to a player's death), which do not flush loaded game assets from memory.

Here, on the other hand, is a pattern of allocation that is not well-behaved:

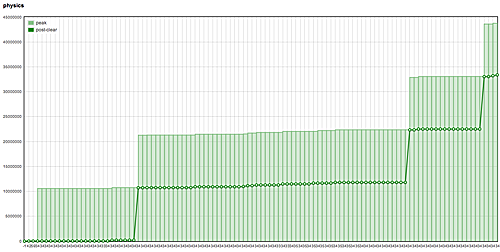

The above graph provides smoking-gun evidence of a memory leak in our physics system. Total allocations clearly jump up by a similar amount at certain moments. Because all ticks along the x-axis are labeled with the same index, we know that the same level is being loaded over and over again. But since the jumps don't occur at every instance, we also know that the leak is intermittent.

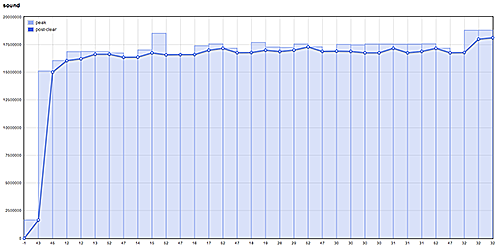

Tracking allocations in this manner wasn't just useful for finding memory leaks. It occasionally helped us realize when we'd done something stupid. For example, at one point I'd unwittingly broken the game's sound asset preloading. Following my mistake, allocations to our sound heap ended up looking like this:

Pretty gross-looking, but in the case of our sound system, the upward trending was not a sign of leaks. Rather, commonly-used sound effects were being loaded on-the-fly and were remaining resident in memory. After re-enabling the preloads, sound allocations returned to a calmer allocation pattern:

During BloodRayne's post-mortem meeting, there was much mutual back-patting about the success of our metrics system, but it was generally agreed that we could have used more of it, and we could have used it earlier. Still others bemoaned the fact that we didn't have a system like this in the final version of the game, so we could see what players were doing with the game after it was released into the wild. In any case, the consensus was that we'd barely tapped the potential of our metrics system, and that there was no way any of us was going to make a another game without it or something similar.

From a technical standpoint, there are some obvious things that would really improve the system described above. Clearly, if we'd really wanted to receive player data from the consumer version of the game, or if we wanted an external QA team to help us produce data, we'd need proper support for DNS and HTTPS. Also, if we wanted super-granular datasets, of the kind that could produce "heat map"-style data visualizations, we'd probably have to sacrifice some flexibility in the data schema and use something that allowed us to reduce the relative verbosity of our outgoing data.

But beyond the boilerplate network tech, what we really could have used was a more precise means of describing where each piece of data was coming from. We did in fact supplement our data with a timestamp, an ID for the source hardware, and the executable's revision number, but we had no generalized method of identifying each unique boot-up or playthrough of the game (heap allocation tracking used an ad-hoc method of passing an integer counter that was incremented for each successive sample sent to the server). Moreover, we had no means for filtering out junk data that we didn't need. For example, if a QA guy is playing the game to see what happens when he dies a hundred times in the same spot, then the data he is generating will not be particularly useful for the purposes of play-balancing the game. My impression is that a mature metrics system essentially needs some way of managing demographics--that is, it needs to be able to collate and filter the data based on where the data is coming from, who generated it, and the context it was generated in.

This post originally appeared on the author's technical blog. Thanks for reading, folks!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like