Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Jedrzej discusses how current model of game development is influenced by increasing presence of players. The ways for studios to retain control over their vision under the barrage of players' inputs are explored.

The rise of crowdfunding paves the way for increased presence of players in game production. It begins with beta testing, then leads to opening up of the alpha build and your art assets, and before you know it, it has taken your soul – and you cannot produce games without your players. Does that fear sound familiar?

Of course, it doesn't have to be like this, and probably won’t: despite numerous benefits from embracing customers in production of games, the role of game development studio as the coordinator of the process as well as curator of the vision remains undisputed. What is interesting, nevertheless, is the fact that we can start seeing game development studios not as monolithic game production temples, which open their gates once in a century to let a new game out, but as central nodes in a vast and diverse network where value is produced together with other firms (middleware, all kinds of outsourcing, motion capture and the like), but also with a little help from the customers. It is a new and exciting era indeed, and it still remains to be seen how tightening cooperation between game developers and their players will affect the dynamics of game production.

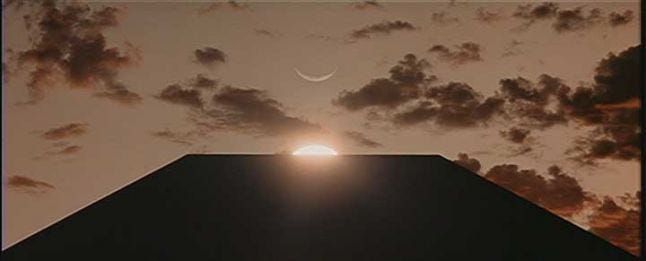

Figure 0. Sheer use of the word 'monolith' justifies this picture perfectly. Still from 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick.

Figure 0. Sheer use of the word 'monolith' justifies this picture perfectly. Still from 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick.

The flip side is the fact that game developers will be less and less able to afford not integrating customers’ inputs in their game production practices – as I already mentioned in my last article. There is too much value to be gained from the interactions with your players, not only as QA testers or sources of feedback on new features, but also as generators of ideas, barometers of market needs and skilled producers of art assets. It will become a common industrial practice to build games with the help from the players, and those studios which will decide to resist this trend will be not only losing out on cutting the costs of production, but also alienating their fan base.

Of course, all of those changes involving customers becoming more and more involved are not easy to implement – the fact that their presence is disruptive to normal game production schedules is already well-known in the industry. Currently, dedicated employees, or employees from the departments completely unrelated to game development (various practices are embraced in different studios) fulfill the roles of gatekeepers, coordinators and judges of the players’ inputs. If a senior member of the development team becomes involved in screening players’ inputs into development, she will very quickly find huge amount of her time being eaten away by those tasks. Deep technical, as well as artistic expertise are required to really judge whether a players’ idea can really fit into the game as being designed by the studio. Not to mention the additional problem here, which is the feasibility of those ideas. Many ‘brilliant’ suggestions that customers discuss on the game-related fora are completely outlandish from the game production perspective – they are either financially impossible to implement, technologically unfeasible, or represent demands of vocal minority, which has nothing to do with what the majority of your market wants.

There are some signs out there, which would suggest that game development can be done outside of commercially-driven game development studios. The examples here would include Black Mesa (the recent mod of Half-Life) and open source software development (albeit with some caveats; I have discussed the differences between open source software production and co-creation of games in my article from August 2013). Although both of these cases are a far-cry from game development, they do contain some seeds of processes that, when scaled properly, can gain significant traction in the mainstream game development. Black Mesa is ‘just a mod’, which is easier to make than producing a game of the size of Half-Life from scratch (complete with gameplay design, level design, music, art and many others), but still some parallels in processes employed can be observed. Open source software is also easier to make than a game from the development perspective – no need to integrate technology with art, gameplay design, AI, motion capture, sound and voice acting, just to name a few. Not to mention the markets and end uses for both Black Mesa and open source software – none of them is a unique artistic product, which must sell in large quantities in a demand-uncertain environment. Nevertheless, some of their practices (production over a distributed network for Black Mesa, and iterative cycles of feedback from users’ community for open source) have already been identified and adopted by game development studios worldwide.

Despite those dark thoughts and disturbing visions, let’s now refocus our gaze on the reasons why game developers' position remains undisputed. They have been illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Four main aspects of game developers’ control over game production.

We will now turn to discuss those aspects in turn:

Artistic message and content – game development studio (or its business partners, such as publishers) are in control of the intellectual property of the game (which can be developed in-house, but which can also licensed-in from external partners). As long as the ownership of individual bits of IP that go into games (single music tracks, useful lines of code, narratives) could be given to individuals, the attribution of general game (franchise) IP would be controversial to manage without a collectively-owned legal entity (such as firm). Moreover, games need a coherent and centralized design to be ‘fun’, as well as to exhibit congruous set of gameplay rules. Artistic message conveyed by in-game art, cinematics, voice acting, music – just to name a few – must also be coordinated and planned, so the game can have its unique selling points.

Competitive market rationale – games are products that must be sold to end users and bring in revenues. Understanding of players’ needs stemming from close relationship between them and the studio is not always is a good thing, either. Customers are generally seen as unable to radically innovate, their communities still largely dominated by ‘vocal minorities’. Players can easily lock-in studios on the existing market trajectories by demanding more of the same product, at all times. Only with a studio managed as business operations, it is possible to strategize in real-time the commercial applications of production in response to the markets, to which the ultimate product and service should appeal to.

Coordination of the value adding function – digital games are not easy products to make. They require integration of technical and artistic functions over extremely complex and lengthy production cycles. As long as it is possible to make small productions without large organizational backup (examples here would include indie games, often developed by individuals or small teams), production of AAA titles would be impossible without a centralized management and coordination entity. Recent examples of various project management techniques in game development (such as Scrum, Agile, Lean, XP and others), and general departure from Waterfall paradigm, show the importance of coordination and synchronous administration of various studio functions.

Finances, capital, wages and investment – despite the advent of crowdfunding as a viable method for financing games, central function of the firm in raising funds for game development is still present. It is the studio which prepares the prototype and game concept, it is also the studio who chooses the type and time of financing. It is track record of the game developers, as well as reputation of the company overall, which attracts backers’ support and investors’ trust. Beyond its applications for small and medium-sized games, studios provide an indispensable structure for interacting with publishers, who can finance larger projects. Furthermore, management of money issues, such as milestone payments, employee salaries, equipment purchasing and software licensing still remains an obvious domain of the firm, and could not be easily taken on by individuals.

From those observations, we can assume that the position of game developers in retaining control over direction and form of game production remains undisputed – for now. Nevertheless, there is a pressure exerted on the studios from the wider socio-cultural and market contexts, which has been increasing in intensity in the last years. The zeal of players to influence developers at various stages of game production, overall opening up of the industry to creativity of its customers (via modding, multiplayer games, mass testing and the like), as well as general lowering of the barriers of entry into game production business (exemplified by the rise of indie games and platforms such as Unity Asset Store) lead the charge. On the game developers’ side, there is also an increasing desire to co-opt players’ support in more ways – be it for financing purposes (which means creative freedom and greater independence for the studios), customer relations, or simply attempting to do things better and cheaper (as shown by public beta tests). Those transformations herald changing paradigm of game development in an industry, which seeks to fight high production risks (and associated demand uncertainty) as well as the erosion of creativity (also due to the risk aversion). With both parties willing to intensify their collaboration, it is only a matter of time before a new paradigm of game production sets in – one with a significant input element from customers.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like