Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

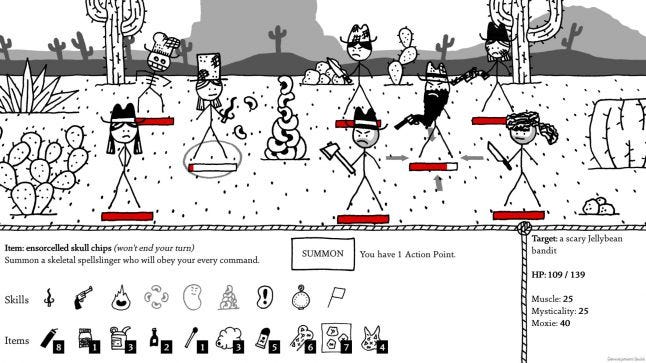

RPG West of Loathing takes players to a ridiculous stick figure old West, having players duke it out as Snake Oilers, Beanslingers, and Cow Punchers.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

RPG West of Loathing takes players to a ridiculous stick figure old West, having players duke it out as Snake Oilers, Beanslingers, and Cow Punchers. This silly take on the setting aims to crack players up at every turn with its constant absurdities and zany moments, leaving no stone unturned to sneak a joke inside.

Gamasutra spoke with Zack Johnson, Riff Conner, Victor Thompson, Wes Cleveland, and Kevin Simmons of Asymmetric, developers of West of Loathing, to talk about how they worked to make the player laugh as much as possible, the challenges in designing a game around making the player laugh, and how they worked to draw out so much silly expression from the stick figure characters.

Johnson: I grew up writing little games in BASIC, but never thought I'd get the chance to do it professionally until 2003, when I was able to turn my experience in web development into Asymmetric's first game, The Kingdom of Loathing.

Conner: Mostly just Kingdom of Loathing, although I’ve dabbled with interactive fiction authoring tools such as Inform 7 and Twine and (in my childhood) World Builder and Hypercard.

Thompson: I've been working on video games as a job for a little over seventeen years, and as an independent games contractor for about five years. [Asymmetric Note: Thompson worked on AAA on titles like inFamous and Excite Truck before going indie.]

Cleveland: I started out making cartoons for myself and posting them online for some kind of validation for the hours and hours of work involved. Then, about 10 years ago, I was introduced to Zack (Johnson) and Kevin (Simmons) by a mutual friend. They were looking for an animator for the smash hit video game, Word Realms, so I signed up with them and never looked back! [Asymmetric Note: Word Realms, Asymmetric's first game after Kingdom of Loathing, was a commercial flop.]

Simmons: I was a freelance photographer before I fell into video game development by accident. I've been working for Asymmetric since 2005, working on Kingdom of Loathing and all our other less-well-known games.

Johnson: After more than a decade working on the always-online, constantly updated Kingdom of Loathing, we were excited to make something standalone. Since Kingdom of Loathing is so all-over-the-place in terms of its content, we also found the idea of sticking to a single genre very appealing. As to why it's a Western, I guess I just like cowboys.

Conner: A western just seemed like a nice sideways step from the medieval fantasy we’d been doing in Kingdom of Loathing for so long. It’s low-tech and adventuresome enough to be comfortably familiar, but different enough to feel fresh. Plus there just aren’t enough good westerns in games."

Thompson: West of Loathing is based on the Unity engine, and also includes a lot of our own C# code.

Cleveland: Zack sent me art files that I sometimes needed to tinker with in Photoshop, then I animated using Unity’s on-board animation tools. I use a plug-in called Puppet2D to do my rigging and skinning.

Simmons: About three years. We started prototyping West of Loathing in late 2014, and made a proof-of-concept Unity project in early 2015. We thought it'd take about 12 months to build at that point, so of course the game came out about two-and-a-half years later, in August of 2017.

Johnson: Luckily, we've been doing this kind of humor as a team for so long that it comes fairly naturally. We just have this kind of low-level company dogma that requires every sentence we write to at least TRY to be a joke. Well, every sentence except that last one.

Conner: The two main problems I personally face in writing funny dialogue are: firstly, not being able to tell any more if something is funny after I’ve edited and tweaked it and read it a dozen times and it’s no longer surprising to me. Ideally, I’d like to go back for a reread a couple of months later after I’ve forgotten what I wrote, but that’s not always an option. So, I kind of just have to trust myself.

The other problem is that comedy is so reliant on... hmm, what was it... tip of my tongue... starts with a T...

Anyway, sometimes the rhythm of a joke is difficult to translate into text. How do you make a reader put the pauses where you want them to go? I get accused of overusing commas a lot, and this is basically why.

TIMING! That was the word I was trying to think of. Timing.

Cleveland: Zack’s art has a lot of built-in personality, so it’s easy to translate that into humorous animations. “Brade”, the merchant in Boring Springs for example… Just by looking at the enthusiastic smile on his face, I could tell this guy really wanted to make a sale! Sometimes, the constraints of the art style and dev pipeline influence my decisions, too. Like, how the hell am I going to make this coiled up snake move across the battlefield?!

Johnson: Because you can't really control the order in which players encounter things, I think it's critical for a comedy game to be funny (or at least TRY to be funny) at every single opportunity. When you can't rely on consistent pacing, it becomes important to shove jokes into every single nook and cranny the player might explore.

Conner: There is a tendency, even a compulsion, to want to throw in a bunch of pop-culture references and memes. In early Kingdom of Loathing, we leaned into it really hard, to where it was sort of Kingdom of Loathing’s 'Thing', although lately, we’ve backed away from it some.

The problem with references - and this is easy to forget - is that you can only really use them as part of the context or setup to a joke, not as the punchline. “Hey remember that other funny thing someone else made that you liked?” is not a joke. And people are getting savvy to that.

The *other* problem is that if a pop-culture thing doesn’t stick hard enough to become a real cultural touchstone, its shelf-life is nil. In Kingdom of Loathing that wasn’t as big of a problem because we could dump content into the game and have people seeing it immediately. But, if you put that kind of stuff in a game that won’t come out for another year and a half, you’re risking putting in jokes that, at best, people won’t know what the hell you’re talking about, and, at worst, they’ll think you’re a total ass for even mentioning such a dried-up old meme.

In West of Loathing, we had a rule: no anachronisms, no references newer than 1898. *Mostly* we stuck to it, though there are some exceptions. Like I said, it’s practically a compulsion.

Cleveland: I feel like the medium is wide open for humor, and you’re only limited by your imagination… and that can be the difficult part. Sometimes it’s hard to come up with a funny way to animate a guy washing dishes. I suppose knowing when to say when is something that you have to keep in mind, too. If every character on screen is always doing something zany, then it’d be too much.

Johnson: Well, I've stuck to the stick figure style for so long because it's the only one I've got! That said, the style really couldn't help but evolve in the 15 years I've been doing it, and it feels a lot more like a choice now than a limitation. I was concerned that it would be difficult to animate in a convincing and entertaining way, but Wes (Cleveland) really knocked it out of the park.

Cleveland: Back when I was doing cartoons and posting them online, there’d always be a bunch of stick figure animations out there. Usually of some kind of martial arts fight scene. I thought they were garbage. Now that I’m doing it, however, I feel it’s a legitimate and respectable means of expression. Seriously, though, I feel like the simplicity of the art style actually makes the animation stand out more. I’ve always tried to make the characters I animate expressive, but I think this format forced me to up my game a bit to make these simple stick figures look alive.

Johnson: They're all fantastic! I spent a ton of time with Heat Signature and absolutely love it. And Into the Breach is turning out to be just as addictive as FTL.

Conner: Night in the Woods is fantastic, and I will be extremely surprised if they don’t beat us, damn their eyes. The game I’m most excited about getting to play in the near future is Baba is You, which looks fascinating and extremely up my puzzle-game alley.

Thompson: Not as many as I would like. I think Vignettes is very cool and relaxing. The main mechanic of it feels completely magical. I had a chance to play part of Into the Breach, and that game is going to be amazing. Really tight and engaging.

Cleveland: Into the Breach - I’m super into turn based strategy games, mechs, and pixel art, so Into the Breach has me pretty excited. Cuphead - As an animator it makes sense that I’d be drawn to a game based on the historic “rubber hose” period of animation. I mean, it’s absolutely beautiful.

Simmons: I've played about half of them across all the categories, and they are all amazing. I don't envy the IGF juries in having to compare such wildly different games! Into the Breach and Baba Is You are two of my favorites. I definitely recommend checking them out when they are released later this year!

Johnson: We were extremely fortunate to have an existing fan base when we released West of Loathing. The marketplace is so crowded right now that even a great game that's marketed perfectly can still just fly totally under the radar.

Conner: Too many games! I have no earthly idea how someone who’s just starting out gets any attention in this tidal wave of games. Everyone stop making games for a little while ok? Let people catch their breath. Jeez.

Thompson: This is a boring answer, but the biggest hurdle is always money. Even for those who aren't in games for profit, they need to earn a living somehow. From the same point of view, I suppose, the corresponding opportunity is micro-publishing (or similar types of agreements) which can get a small team with a great game enough money to live on while completing their project.

Cleveland: Definitely, for me, it’s networking and hustling for that next gig. I really suck at it, so I’m counting on West of Loathing spinning off successful sequels for at least 20 years.

Simmons: Barriers to entry have never been lower - there are tons of powerful tools available for free to make video games, and basically anyone can get their game out to people via services like Itch.io or even Steam (for a small fee). That also means that countless projects are being released all the time. If people want to make a living making games, they really need to distinguish their work in some way to rise above the rest, and that just gets harder every day.

You May Also Like