Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

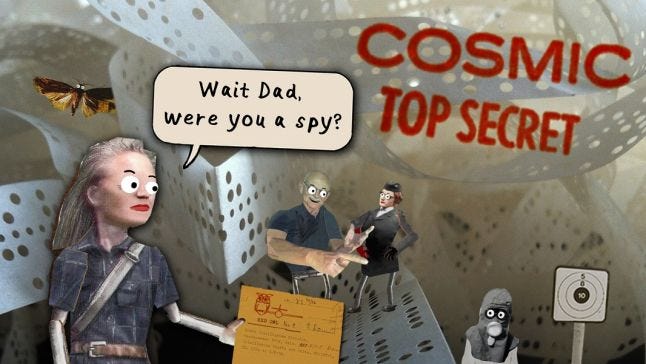

Cosmic Top Secret tells a papercraft story of Cold War secrets and family connections, taking the player on an autobiographical journey through the stories of a developer's parents.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

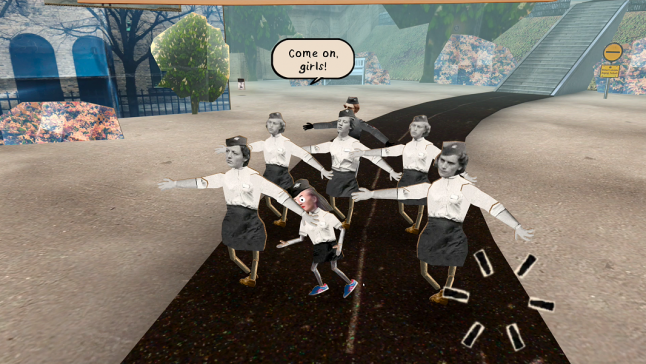

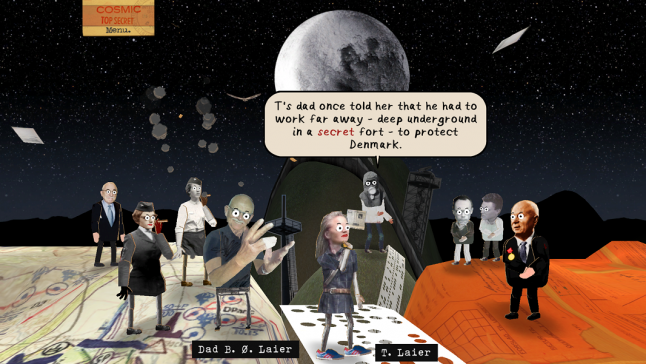

Cosmic Top Secret tells a papercraft story of Cold War secrets and family connections, taking the player on an autobiographical journey through the stories of a developer's parents. The player, as a paper person named T, will follow in their parents' military footsteps, learning more about their history as members of Danish intelligence while also exploring their connections with their daughter.

Trine Laier, director of Cosmic Top Secret, had a talk with Gamasutra about shaping these memories and stories into an interactive experience, what it meant to share these memories and make the player feel them, and the importance paper played in the stories and sensations players could take part in.

I was an animator on games, films, TV, web, and blah blah. I fell more and more and more and more in love with games. I wrote a novel about online gaming, I researched and ended up with a job as a director in the Danish games industry - I got fired and blah blah, took up Java programming at IT University, went to film school, blah blah. Teamed up with producer Lise Saxtrup from Klassefilm on the making of Cosmic Top Secret, because of her insight into producing documentaries. We shared a mutual vision for a documentary game. A game with meaning and blah blah.

I wanted to make a game that would be fun and engaging but at the same time convey my personal feelings about my family, our secrets, and the history we share – despite being born at different times. I started interviewing my dad and followed him around in his military world; soon that mechanic of “following dad” became the theme for the game, a theme that is both physical and mental and would work both for a story and a game.

The concept started out as quite experimental and technically demanding: A game running on computers but controlled by your mobile phone. We shifted to a more classic adventure game – but still retained that unseen (don’t you think?) mix of documentary footage, personal storytelling, and emotional and experimental mechanics.

Mostly Unity3D. It was a bit of a no-brainer to opt for Unity3D for this project; the flexibility of the platform, coupled with the easy porting options to mobile/PC, made this pretty ideal for a small team such as ours. Not to mention that Unity3D is also Danish and we used to work with them next door when we were all kids in the games industry in Copenhagen. Alhough we have to admit that the integration of film elements in the game has been quite a hassle. Still is.

This is a project dating back to 2012, but we’ve also worked on other games and films during this time too. In its earliest form, it was pretty rough around the edges, but the majority of the basic concepts remain even now. Fast forward a year later and we received funding from the Danish Film Institute, amongst others, to go ahead and really take this project up a gear. It’s a passion project that has come leaps and bounds over the past six years, so we’re delighted that we’ll soon be able to share it with the world.

I needed to present the idea for the game within the next half an hour, before a big meeting. I started by drawing my dad as a wolf – a wounded wolf, but I felt it was too far away from my dad’s expression – it didn’t feel right. From there I cut out a photo of him and mounted him on cardboard; almost like a paper puppet.

I knew from the first moment that there was an exciting story about my dad and, as you discover in level 2, mom’s work for the Intelligence. I knew that for every cool thing I would showcase about their work, I’d also showcase something not-so-cool about both their work and us as a family; about our fragility as human beings, being too strict, being too soft, being too awkward, and so on. In that sense, paper fit perfectly.

Paper is used for all kinds of communication; paper can be strong and sensitive at the same time. I kinda wanted the same duality or contrasts in the game design, dealing with super serious matters in a humorous and entertaining way – if I should actually “be allowed” to drag you, the player, through my personal take on the history of the cold war and my family, it must be the full uncensored story.

As my dad would say: it’s all or nothing! (Got him on that.)

Some of it is related to childhood memories, also from my dad’s childhood (pop-up books and paper dolls etc.) It’s kind of a shared child’s perspective of the world that I’ve now put on a stage, from the perspective of me as an (almost) grown up.

Characters aside, the paper-themed style opens up a few doors for us: cheaper production costs, direct implementation of punched paper tapes and old documents from Intelligence, live video footage of real people interacting with paper characters is a pretty unique concept that we are proud to include.

Playfulness is alpha and omega for it all. Doing the story - not “having it told”, and the bodily experience that affects the feeling of the story. Choosing how much time you want to “play” (roam around in the world etc.), do you want to jump or throw hand grenades to get access to certain areas, and which extra “dossiers” (missions) you want to complete (do you for instance choose to go for the “Khrushchev's Poop”, “The Apparatus Case” or “Mom's Red Order” missions?). All that adds another dimension to the game and reflects on the reception we’ve had.

I love the reaction all players have the first time they roll the avatar (me) as a paper ball. They tend to just roll and flick around with the ball and the scenery – I don’t know what this term is exactly, but this “doodling” way of playing really triggers certain mechanics in our body and brain. It’s also why the game focuses a lot on my dad’s body; because of my childhood memories of a very physical and active dad always busily on the way to something. That’s the core of the navigation - go follow dad!

I’ve had a lot of ambition (and still do) to tell our family story as honest and sincerely as possible. I’m very inspired by Tarkovsky’s The Mirror - the film art, and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle - the autofiction style and believe that it’s through the author/creator’s honesty and eye for details that truly great moments of revelation will arise. BUT I’ve had long periods of waking up in the middle of the night haunted by guilt. I THINK I’m treating my family and all the other characters in the game with respect and love, but I still FEEL guilty about it.

I’m aware that it’s an even wilder step turning people into video game characters compared to being a person in a book or documentary. The stuff you can do actively in games, like throwing hand grenades at people, and as many testers have done, shouting and disagreeing with other characters in the game; That’s why I had to take the lead role myself, and now I’m suffering from tester feedback; they all LOVE my family, some even want to be adopted by my parents!

But the funny thing is no one says that I’m cool as a character. My husband comforts me and says it’s the Tintin syndrome: we all love Haddock and Tournesol, but Tintin himself is boring. Those are just my feelings of vanity. The only thing that really matters is, of course, what the player feels. Obviously, I want the player to be entertained and taken care of. I want you to feel the same excitement as I felt - compassion for the old history and family stuff and acceptance across generations and across ideologies. Though the setting is the Cold War, I want the player to feel the warmth between my dad and I - and to reflect on their own relations and family secrets that we all have - Cold War agents or not.

I’d love to give praise to every team and game nominated, but if I only had to pick a few, there are three standouts for me: Cuphead has been a labour of love, and being an animator myself, taught to animate with the Disney principles in hand on paper and on celloids. I’m quite emotional for that musical and dynamic style that stems from the first animations like Silly Symphonies. Vignettes is another kind of beauty game that feels much more modern and cool, and finally, Everything is going to be OK is super charming and politically relevant.

Discoverability across all stores (mobile and Steam) has been an issue for a while. Steam is now incredibly saturated, but it does a lot to feature a variety of different games across different categories (by tags, just released, coming soon etc.), but it’s still very difficult to stand-out and make a viable product just launching on Steam.

Hurdles:

Attracting an audience and (getting new audiences)

Getting the attention of the audience

Financing the unknown

Opportunities:

Creating the unknown

Exploring game design

Create diversity in games and thus addressing new audiences for games

In addition, finding that fine line between having the capacity to both make a game and attracting new audiences (while growing your existing one) is really challenging. It’s a double-edged sword; you need to spend time creating a quality game, but you also need that fanbase there so that you’ve got baseline interest at launch.

You May Also Like