Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

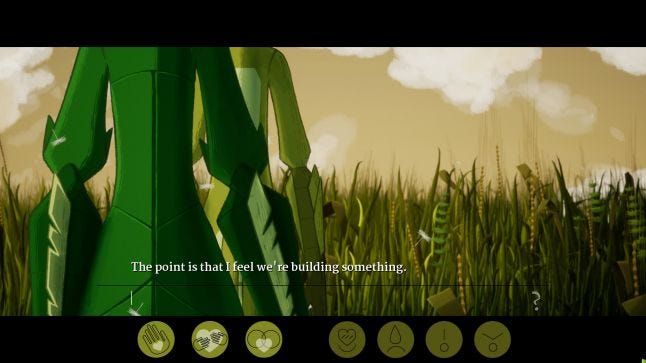

Don't Make Love puts the players in the role of mantis lovers on the verge of a life-changing decision, having them use their own words to talk through this difficult decision.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

Don't Make Love puts the players in the role of mantis lovers on the verge of a life-changing decision, having them use their own words to talk through this difficult decision. Making love will result in the male mantis' death, but intimacy is important in their relationship, leaving players with an emotional, complex conversation to have.

Gamasutra spoke with Dario D'Ambra, lead developer, and Nina Kiel, artist, about Don't Make Love, learning about why the developer chose to let the player use their own words to have this difficult conversation, and about trying to portray more meaningful representations of relationships in games.

D'Ambra: I don't know if I have a proper background. Don't Make Love is my first commercial game. I have a bachelor in Modern Literature from back when I wanted to become a writer or a filmmaker. Despite that I have played video games since childhood, I only mildly considered the possibility of developing my own. It was during my masters in Digital Humanities that I started to use exams as an excuse to develop small interactive experiments. Still, it was only while I was working as a java programmer that I realized that I really wanted to develop videogames.

So, I became a student at the Cologne Game Lab and started to develop games as a student. The Game Lab really helped me hone my skills and to have a different and broader perspective on games. I guess my background is more about deciding to make games rather than make games itself.

Kiel: I started working on game projects about eight years ago when I was in my first semester of studying design. Game development was barely covered in the curriculum, but luckily there was one animation class that offered the opportunity to work on a flash game. This was the first time I considered working as a game artist, because cooperating with a group of incredibly creative students and seeing my own character creations coming to life was one of the best experiences at university.

In 2011, I joined a group of hobbyists who met every Sunday to improve their visual and programming skills while working on a bigger project. In 2015, I finally decided to pursue a career in both game development and journalism, and started studying “Game Development & Research” at the Cologne Game Lab – which is where I met Dario (D'Ambra).

D'Ambra: The idea of the game came from an observation and a question. The observation was that there aren't many games that explore the dynamics of a relationship. Many games feature the possibility to have a relationship, or are about starting a relationship, but not about coupled life. The question was how praying mantises would live with their tragic situation (eating or being eaten by the person you love the most, your significant other) if they had human feelings. Once I had both in my mind, it becomes obvious this was an interesting starting point for a game. Later on, Nina made me discover that there are way more games about relationships than I thought, but we still think DML has its own charm.

Kiel: When Dario told me about his idea, I fell in love with it right away, and really wanted to turn it into a game. Back then, I was working as a part-time games journalist and had a review series called “Random Encounters”, which focused on romance and sex in games, and, let’s face it, most releases were and still are incredibly bad and never look beyond the process of courting and initiating sex. So, the thought of being able to co-create a game that explores relationship dynamics on a deeper level was particularly appealing for me.

D'Ambra: We decided to go with Unreal Engine, which is not great for 2D, but allowed us to easily integrate Chatscript, the software we use for the language recognition.

D'Ambra: Being the writer and programmer of the game, I worked on it for a fair amount of time. We started the development around February 2016 and released on October 26th, 2017, so it's 1 year and 10 months, but none of us worked on it full time.

Kiel: Dario definitely put the biggest effort into this, but we all had to assume several roles, like, in my case, working on the graphics, proofreading some of the texts, testing every new version of the game, and doing a bit of PR. It was pretty intense, since we had to make money on the side and attend class while developing the game.

D'Ambra: As I mentioned previously, we used a software that really helped us in recognizing the grammatical forms of the words. The main difficulty is to guide the players through the conversation; they should be free, but at the same time, you have to remind them that there is a specific conversational topic they should stick with. You can use different tricks to keep them on track. We mainly did two things: recognizing when the player was "misbehaving" and provide a spot-on reaction and sway the player through the writing. It's more about providing the impression of freedom rather than true freedom.

D'Ambra: Because the game is about communication in a relationship. When you have a problem, you talk about it, don't shoot at it. Communication can be tricky, though; we wanted to provide that same feeling of freedom, but also that helplessness that we sometimes experience when talking to others without being understood. I think pre-made responses simply are not able to provide that nuance, even though good writing can compensate for it.

Kiel: I think the main problem of most romance- and sex-focused games is that they provide you with very few options to choose from, so it’s difficult to become immersed, especially for those outside the target group of these products. Stories always reflect their creators’ worldview to some extent, and this is particularly true for erotic stories, even if they offer some degree of interactivity. This is why we didn’t simply choose the possible inputs ourselves, but showcased the game numerous times to read the logs and find out more about the thoughts and behavior of the players we wanted to address. This is, hopefully, how we managed to cover many different ways of behaving in a relationship.

D'Ambra: I see the mantis couple as an excuse, a metaphor. I wanted to tell a story where you cannot win or lose (life is not as simple as that), but only accept the situation and try to find a workaround, as often happens in our lives. In a world where social relations are easy to make but complex to understand and manage, I think stories can and should be more helpful. We are constantly subjected to simplified representations of love and sociality that mirror an idealized world that probably never existed. As storytellers I think we should provide a more realistic and nuanced depiction of our society to help understanding its complexity. In turn, I hope that a better comprehension would bring more empathy to the people around us.

Kiel: The premise hopefully helps the players to take the conversation they’re having in the game seriously. Of course, they’re also invited to play around and try silly or even offensive approaches, but knowing that there is something at stake here ideally creates some tension which does not exist in many other romance and sex games.

D'Ambra: A big role was teamwork. The most important thing was to have a shared vision of what feelings we wanted to instill in the player, then everyone worked to achieve that: music, art, and writing. We tried to make the players understand that the situation they're in is serious and complex. They could identify with the theme of the game, but of course, art helped a lot in making the mantises more likable, and music makes always a huge difference in creating an atmosphere suitable for identification.

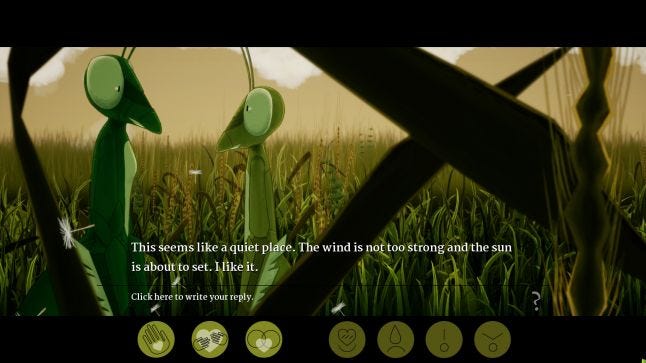

Kiel: I tried to make both mantises look humanoid to some degree in order to facilitate the identification process. We knew from the beginning that insects might not be ideal protagonists, since many people perceive them as gross and scary, so I gave them big, expressive eyes and a slightly humanoid body shape. I suppose that we succeeded, because so far nobody complained about our mantis couple.

D'Ambra: I have to admit that I didn't play many of them. Of the games I played, I really enjoyed Baba Is You, and I think it deserved all the nominations. I also liked Kyklos Code, Bury Me My Love, and Dead Cells. Among the finalists and honorable mentions that I would like to play are: Night in the Woods (that I hope to play before the award ceremony), Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, Hollow Knight, Echo, Cuphead, and Everything Is Going to Be OK.

Kiel: So far, I’ve played Night in the Woods, Cuphead, AER - Memories of Old, Everything Is Going to Be OK, and Kyklos Code, with Night in the Woods being my favourite of them. The game’s certainly not perfect – I’m looking at you, dream sequences – but I just loved the art style and the complex characters. Bea was one of my favourite game characters in 2017, and Gregg and Angus are the most adorable couple I’ve seen in years.

D'Ambra: Being indie is super difficult. Not having a marketing/fund-searcher guy proved to be a big commitment challenge, and we managed to develop the game because we had external sources of income (parents, savings, or jobs). This was also our first commercial game, so we had all the problems of first-timers.

I think one of the biggest hurdles right now is the audience. We need to reach a broader audience - games are not just for gamers only (whatever "gamer" means), but for everyone. Yet many people still have a lot of prejudices and are outside the reach of the game press. Don't Make Love was designed to be a game playable by everyone, but in this regard, it is super difficult to create awareness for people that don't play games who would be interested in ours.

Kiel: I think the biggest advantage and disadvantage we currently face are tightly connected. On one hand, we can now choose from a huge variety of games, with some of them being incredibly complex, while others are short, yet powerful, well-designed, or simply thought-provoking. I’m so glad to see that more and more people give game development a shot, because they allow us to see the world from so many new perspectives and finally address players who previously were not considered as an audience.

On the other hand, this ever-growing selection of really good games makes it increasingly difficult to attract attention. I seriously never expected to be selected for the IGF award, despite being rather confident in our project, because there’s just so much to play and share out there.

You May Also Like