Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

While "outsourcing" has a certain image in the minds of many, Virtuos -- one of the biggest outsourcing houses in the world -- is not precisely what you'd expect, and Gamasutra traveled to their Shanghai headquarters to find out more from CEO Gilles Langourieux.

[While "outsourcing" has a certain image in the minds of many, Virtuos -- one of the biggest outsourcing houses in the world -- is not precisely what you'd expect, and Gamasutra traveled to their Shanghai headquarters to find out more from CEO Gilles Langourieux.]

Virtuos was started in Shanghai by three partners -- including CEO Gilles Langourieux and production director Pan Feng, who spoke to Gamasutra at their Shanghai HQ about the shape of their business. Their goal is to provide sustainability to the marketplace in a time of rising costs, and their ambition is to remain a partner that companies feel there is value in working with.

The company was founded in 2005 by ex-Ubisoft Shanghai staff, and by the end of that year reached 70. Now, Virtuos has 600 staff across studios -- one in Shanghai and one in Chengdu.

While the company now develops games internally from the ground up, and also contributes to Hollywood films, the primary focus of the operation is outsourcing -- art and animation (from props through full levels) and also programming.

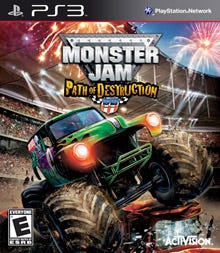

The work-for-hire development process has resulted in parts of games or full games -- from Activision's Monster Jam to the side-scrolling levels in Disney Epic Mickey.

"We shipped games on PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Wii, DS, PSP, iPad, iPhone, PSN, we have a live demo that's on Facebook as well. So that's how many platforms we're able to touch," Langorieux told Gamasutra.

Why did Shanghai become such a center of this kind of development?

Gilles Langorieux: The history is that Shanghai has always been a city in China which is more open to the outside world. Beijing is more the center of excellence when it comes to engineering -- pure engineering and pure art, Beijing is the center of excellence. But when it comes to openness to new ideas and the open world, Shanghai comes first. And this is the reason why we selected it when we wanted to open the first game studios for Ubisoft in '97.

I think it's also why TOSE, which was the first Japanese company, selected it. I say it's this combination of -- there is excellence in China, but also there's more openness to culture. There was a tradition of movie production in Shanghai before the war and the revolution, and there are some cartoon companies and some local game companies which may have inherited a little bit of that tradition.

Art outsourcing is primarily thought of as something for major console-scale games. Your internal development seems to scale all the way up and down the chain for your products.

GL: We can take examples from games that we've shipped this year, it goes from helping a small developer like Ludia, I don't know if you're familiar with them; they do games based on TV shows like The Price Is Right, Family Fortunes.

So we have helped them adapt their games from the console platforms that they were originally developed for, to more online oriented platforms like the PSN or the iPad. So this is a fairly simple, compact project. It involves most of the skill sets -- producers, designers, engineers, artists -- but it's a short time frame; usually less than six months. And for us, that's a small and simple adaptation project.

On the other end of the scale, we shipped the new iteration of Monster Jam for Activision, which we developed on all the console platforms from scratch with technology which belongs to Virtuos. And that's a much longer effort; it's nearly a year of development for up to 150 people.

On the other end of the scale, we shipped the new iteration of Monster Jam for Activision, which we developed on all the console platforms from scratch with technology which belongs to Virtuos. And that's a much longer effort; it's nearly a year of development for up to 150 people.

In between, you have a project like Sid Meier's Pirates!, which we recently redid for the Wii platform for 2K. The common theme is that there's an existing IP, and our client needs to do more with this IP on other platforms. That's the common theme. And they need a partner which is reliable.

Our strengths are about process, the size of the workforce that we can assign to a project, and the fact that we have mature leads who are able to take the games we do to a higher query level than what's usually expected of an actual developer.

What percentage of your staff is Chinese? And which percentage is Westerners?

GL: So out of the 600 employees, we have around 30 foreigners, so that gives us a 5 percent foreign, 95 percent local.

When it comes to your team structure, are foreign people primarily in lead positions? Or is it mixed?

GL: They're primarily in lead positions -- not exclusively in lead positions. For example, there are certain skill sets which are very difficult to find in China. One example is technical art, so we have technical artists coming from abroad. Another example may be concept art, there are some styles which would be more difficult to work on, so we have concept artists from the West. As a matter of fact, besides the foreigners we have in China, we also have a small studio in Russia.

We have that small studio in Russia where we have around 10 concept artists. And we also have a small studio in Paris where we have producers, engineers, and artists. So they help complement the skills that are difficult to find here, and they make us able to reach a different level from the level we would be able to reach if we were working only with the resources of one country.

Do you have Chinese staff in those kinds of roles?

GL: Yeah, don't get me wrong, half of our art directors are Chinese; almost all of our producers are Chinese; all our engineering aids are Chinese. So this is not a studio which is managed by foreigners; this is a studio where you have foreigners embedded in its international management team. And my two co-founders are Chinese, with Pan Feng and Chen Yu. So out of three co-founders, we are one third French, two thirds Chinese.

The stereotype of a lot of outsourcing is that the Westerners sort of come in and run the show. And the impression I get is that's actually going to be very bad for retaining talent for the satisfaction of the people who work in the studio.

GL: Yes, you would be right. It wouldn't be the right approach to set up a foreign company in China, and we've tried to stay away from that in different ways. So the first point that I made earlier is that two third of the management here is Chinese. It turns out I'm the CEO and the face, but if you walk through the studio you will find that a lot of it is operated in Chinese.

Secondly in terms of shelling structure our only external investor is a Chinese company, and it's actually a company that depends on the Ministry of Science because it's a venture fund.

So we're not isolated foreigners in China... We're very much about growing our local staff as fast as we can from junior artists, senior artists, leads, directors, so that we have the largest possible pool of Chinese directors to seed our new projects and to seed our new ventures.

When we opened our Chengdu studio, we were able to hit the ground running because we had -- in the company in Shanghai -- 20 employees from Chengdu in different senior leadership positions inside Shanghai studio. And when we selected Chengdu, we were able to have 10 of them volunteer to go there and start the Chengdu studio.

So if you look at the Chengdu studio today, the general manager is Taiwanese; the other three art directors, two of them are Chinese, one is British; and all the producers are Chinese.

We've got that right balance between having foreigners who can communicate well with clients -- because it's all about communication -- and having strong local talent that has been through the different steps of experience and growth that are required to do the job at the right query level. A final point on that note, our largest competitors in the outsourcing field are Chinese or Taiwanese companies -- and you mentioned one today -- they're not Western-run companies necessarily.

I found it interesting that you said that your strategy is to avoid new IP creation. Obviously for a lot of development studios that's both creatively satisfying and also seen as building potential equity.

GL: I've always thought that if you want to do something, you have to be the best at what you do. So we want to be the best at digital content outsourcing, and that's all we do and that's where we put our biggest energy in.

The bet paid off, because in six years we were able to overtake every single competitor that already existed when we started the company and grow bigger than them. So there's something that we must be doing right.

Beyond this, I think it's a very simple question. You can't compete with your clients. You can't at the same time tell the clients, "Hey! To leverage, to make the most out of outsourcing, you have to establish processes where you're sharing best practices, where you're sharing technology so that we work on par with your teams!", while at the same time, have [your own] team next door trying to build a competing product.

I think it's good sense, but I seem to be isolated in thinking this because too many people view outsourcing as a stepping stone to do your own thing. I just view outsourcing as my end goal. I mean my end goal is to be the best at doing this for the games industry, for the other digital content industries as well.

And there's a lot of equity in value at being a reliable, high quality, profitable outsourcing company; it's just a different path.

Epic Mickey

So is the bulk of your work, in terms of the outsourcing, is still in the game industry?

GL: Yes. We've been involved on some movie production, and one of the examples I can talk about is Terminator Salvation, for which we produced a number of assets. And after Terminator Salvation, we've worked on more movies and we see this as a growing area, but the bulk is still in games.

When the convergence happens, or as it happens, we want to be right there in the middle; we want to have the skill sets and the teams capable of producing assets or shots or levels, which can work seamlessly between games and movies. Some of our clients are going there very fast, and we're going there with them.

At this point, how important is outsourcing to production of current generation, PlayStation 3/Xbox 360 type games for developers?

GL: I think it's becoming quite important. I was having dinner with an independent triple-A developer yesterday night, and they told me very clearly when we talk to publishers today, they tell us that outsourcing needs to be part of the mix.

We need to have established relationships in place with solid outsourcers; we need to have a plan for how we're going to lead our outsourcing if we want to be taken seriously by publishers, because it's not considered as a way not just to arrive at a lower cost for the project, but also as a way to secure the deadlines of the project, because it eliminates a lot of the uncertainties around ramp up times and it also eliminates some of the uncertainties around the ability of the studio to survive post project.

If you... have too long of a period between two projects, it puts the life of the studio in jeopardy in some cases, in the worst cases…

We see it all the time, frankly.

GL: We see it all the time. But if you're able to focus on the core team, that problem goes away. And this is really what is making our life easier and our existence more meaningful is the ability to tell the core teams at the end of the day, you'll have more royalty to share between yourselves because it's a smaller core group and you are more agile because it's more of a team; you can more easily jump from one project to another or wait for a new project because you have less mouths to feed.

We address the same problem from the opposite angle. We have lots of mouths to feed, but the way we address that problem is by working across a lot of different clients and a lot of different projects at the same time. So it's the opposite and therefore complementary approach that we have.

That seems like it could become quite complicated, particularly as games can tend to have very distinct visual styles, right? So if you're ramping up and down and trying to keep people working on many projects.

GL: That's why we're running after scale; that's where we always run after scale. Scale was an issue at the beginning of the company. When we needed different skill sets, producing characters requires different skill sets from producing vehicles or for using prop artists. If you only have a team of 20 artists, you're not going to be able to work across different types, and it's going to be even more difficult to work across different styles.

With scale, we were able to specialize our teams of artists. And we have 60 artists who do only characters, we have 100 artists who work only on environment, and we have 30 artists who produce only vehicles. And within those categories, we even have different leads who have different styles attached to them. That only comes with scale.

Do the staff find that satisfying? To have that high specialization?

GL: What they find satisfying is to have the option. They work in a company where there's probably a larger variety of client project styles than any other company in China, maybe even any other company in the industry. So they have the option.

You ask a good question, do artists want to produce the same type of characters over and over again? No. Because we work across so many different types of projects, we can give them the opportunity to evolve or to change, which is not the case when you're working, for example, on a large scale MMO of the same style for five years in a row. You see?

The local market kind of products.

GL: I'll give you just one number, but in 2010 we received over 30,000 applications. Why are so many people applying to our company? It's precisely because they know that this is a unique teaching ground. There's opportunities to work from anything from a Facebook game all the way up to advanced CG effects, a lot of Hollywood movies. Not everyone Is going to do this, but given the right motivation and skill sets, the opportunities are there.

Do you find that the skillsets in a local area for recruitment are what you need?

GL: So I've always, you know, from the first day that I came to China in '97 I've always been extremely impressed at the level of art schools in China and engineering schools in China. For engineering, the level in math and physics in particular, for art the level in traditional drawing, painting, sculpture and art history; even Western Art history that they are giving in the schools. And this is why we've been successful at growing the pool.

Do we rely only on Shanghai area recruitment? Absolutely not; we recruit all over the country. I was talking to our team yesterday, last year our recruiting tour took us to ten different cities, and we visited nearly 100 different institutions. So that's how extensive the search is all across the country. And only 40 percent of our staff is Shanghai native; 60 percent are coming from out of Shanghai. So we really try to leverage the China pool, and not just the Shanghai town pool.

Do you primarily recruit graduates from Universities? Or do you also recruit from other development companies and other art companies, the way that you might find typically in America?

GL: Yeah, we also recruit from other companies, but the level of experience out there is very limited, so out of the 200 people we recruited last year, I think 60 of them had prior experience and all the rest were fresh graduates.

For the fresher graduates, we have specific training plan, we even opened a training school and we'll show you how we're set up for this. Because the skills they have coming right out of school are not always enough to quickly get into production, so we have them come in, spend three months to be trained on actual, real life cases of increasing difficulty. And after those three months, we select the ones who meet the production criteria before hiring them for good. So we're one of the earliest to adopt this kind of selective training program.

Do your dropouts go work at competitors?

GL: Exactly -- they have no problem whatsoever finding work. Outsourcing in China represents only 10 percent of the gaming production scene, and 90 percent is online game, MMO, casual game production. So these companies are also hiring a lot of talent, and also training a lot of talent.

Code outsourcing doesn't have a good reputation.

GL: So this is something that we've been strong proponents of from day one. You can outsource much more than art, including code, given the proper setups. We've set up the company with a number of security and IP production measures from day one so that clients will feel secure doing this.

We were probably the first company in China to receive source code from major publishers and to work on them. We've had, and we still have, engineers here working as an extension of the central technology groups of some of the major publishers. R&D outsourcing, code development outsourcing, is fairly new to the games industry but it's absolutely not new to the software industry in general. Microsoft, IBM and HP have thousands of Chinese coders working in Chinese outsourcing companies on their code for them today.

So if it works for the general software outsourcing industry, there's absolutely no reason why it could not work for the games industry. It's just that the games industry is less mature from a development practice standpoint, so a number of processes need to be put in place, some IT setups need to be put in place, and also mentality needs to evolve so that this becomes an accepted practice in the games industry as well. But we're doing it today, and it's growing.

So you manage the overall efforts? Or just game development efforts specifically?

Pan Feng: Overall. So we've got two teams of producers. One team is in charge of development projects; the other is in charge of all the art, animation outsourcing.

Is it challenging to oversee both of those things in the same company? Is it more about just overseeing the managers who have their own specialties?

PF: There are plenty of challenges in managing both activities, but the two teams of producers, they are quite independent. So in most cases, I'm providing them with support like noticing and helping solve problems. They are pretty much running purely by themselves, because they've been in this industry for quite some time and they have the experience. Yeah, there are a lot of challenges, but I still manage.

Did you have to implement the same structure as your partners in the West? Did the people who came from the local market have a different expectation about how things are structured?

PF: Actually, we are structured, I think, pretty much the same as our clients in the West. We have the different departments and whenever there's a need we pull people from the talent pool and try to form a project team. And I think the local companies also have more or less the same kind of structure, so I don't think there are any big differences.

We were talking earlier about teams, we were speaking a lot about teams being able to sustain better Western teams by keeping the core creative going while outsourcing art.

Do you think that that's going to really change the way teams are structured across the industry? Because there's been a lot of talk also in the West about studios having to close because they couldn't keep payroll going between projects. So do you think that this is a trend that's building and you guys are helping in it?

PF: Well, I think for Western studios this is the change. Because we've been seeing that over the past years that more and more western studios keep internal teams on the concept and the development of new IPs, but outsource most of the production to other countries, especially in China. And that's also one of the reasons that we're growing so fast over the past six years.

By doing this, I think they can leverage a lot of the overhead and mostly keep the core of their internal teams, and we can provide [our services]. What we're providing is not only extra production capacity, but especially the high end stuff. Every time of the year, you come to our office, like if the art project we're engaging, I don't know, 40 or 50 different kinds of art projects, that gives our teams a lot of good experience that we can use to help our clients.

You have an internally developed engine for your games that you produce here. I was wondering why.

GL: It's not for all co-development projects. For some co-development projects, clients have technology that they're sharing with us, and that we're working off of. Like Pirates! as an example, we worked off the technology that they used for the original game. In other cases, when there's no commonly available technology, we diverge our engineering teams.

PF: We also divide our engineering teams into different areas, like what we did with our art. Some of the engineers are very strong in AI, some are strong at rendering. So I think basically what we're doing here is to provide the client with different options. If they have an existing technology we can make use of it, if they don't, where if they don't have some part of it, our expertise can also help them.

You know, you see a lot of talk about this in the West in the news media. As China's economy improves and grows stronger and stronger, how does that affect the business for you guys in terms of the reasons people select to work with you?

GL: So two, I think, main other points. First, this is an economy where there is a lot of peer pressure on people to improve themselves; to grow up quickly. So when they're looking for companies to work for, the number one criteria is, “Where can I have personal growth?; Where can I be challenged?” A company like ours, which is international and opens up the doors to games on all platforms offline, online in all countries -- U.S., Korea, China, Japan -- is an ideal stepping stone.

The second impact it has is that it puts the pressure on cost, because as people are gaining in skill sets, then their value increases very quickly and a lot of companies around us want to work with them.

So we have to be very selective and very quick about how we evaluate people, and make sure that the ones who are progressing very quickly also see their income progress very quickly and their responsibilities progress very quickly. And let the others leave, because if they stay long they would probably slow down [things]. So everything is moving faster than it does in the West is the point I'm trying to make; people are progressing faster.

We are also getting more juniors in faster -- challenging them, testing them, training them, making them progress -- because there's this appetite all around us for fast growth. On the positive side, because there is this appetite, I see people improving faster, or learning faster, than they did in France for example. They're more hungry, and because of that they go through more tutorials, more cases, more projects than they would in the West where the pace is slower and the opportunities less. As a Westerner in China, this is what is making me excited about working here.

A lot of people in the West think of outsourcing as a cost savings, primarily. And I understand that that's not entirely your philosophy, but that's an element of it. So do you think that that creates economic pressure on you?

GL: Yes, there's definitely pressure on us to keep the cost level at a level which is less than the West, and there's a pressure on margin. Fortunately for us, there's still a significant gap, in terms of productivity between the productivity we have here and the productivity there is outside. So by improving the productivity each year, we're able to keep our cost at the same level.

In six years, our cost has increased by less than 5 percent. In fact, if you consider that the dollar has gone down, our cost has probably gone down in terms of day rate, or by month rate. But what we actually produce for that cost has gone up because we have, on average, more experienced teams, better tools.

How long is this going to continue? I'm not sure. I think there's still a pretty big gap to bridge, so between now and maybe five or 10 years time. Still room.

The biggest savings come out of capacity, the ability to put a lot of capacity online, which would create a large ramp up and ram down of cost, if the studios had to do this ramp up and ram down in the West. [Capacity] is where probably 60 or 70 percent of the savings come from, and that will remain true even if our rates went up at some point.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like