Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How did the PlayStation Vita's puzzle star take shape? Producer James Mielke (formerly of developer Q Entertainment) walks through early concepts for the game, outlines production difficulties -- including never-before-seen in-progress screens and video.

July 30, 2012

Author: by James Mielke

[How did the PlayStation Vita's puzzle star take shape? Producer James Mielke (formerly of developer Q Entertainment) walks through early concepts for the game, outlines production difficulties, including never-before-seen in-progress screens and video.]

Officially greenlit in August of 2010 -- in Paris, where I had brought a handful of pitches to our publisher, Ubisoft -- Lumines Electronic Symphony (as it was eventually dubbed) had originally been conceived as Daft Punk Lumines.

In my quest to reboot the Lumines franchise, which had diminished somewhat since the original first took gamers by surprise on PSP, I thought that one way to avoid criticisms of "just another Lumines with new skins and new music" would be to focus solely on the work of one particular artist. And what better artist to approach than Daft Punk, who had clearly transcended the pitfalls that engulf most music acts.

Not only were they as relevant in 2010 as they had been in the mid-'90s, but they were now iconic, with Adidas/Star Wars crossover appearances, their own movies (Electroma and Interstella 5555), high-quality action figures, and a soon-to-be-released soundtrack to Disney's Tron reboot on the way. Besides, even old ladies who don't know a thing about club music know the song "One More Time".

What I wanted to do was put the player in the cockpit of Daft Punk's pyramid-shaped DJ booth that they tour with, and -- as Daft Punk -- rock the crowd by performing big combos in Lumines. Everything in the game was going to be Daft Punkified, from the HUD, to the soundtrack, to the bassy aural ambience found on their 2007 Alive live album, to the special effects, real-time lighting, bouncing 3D crowd, etc. Since we were developing this for the PS Vita I planned to use the rear touchpad to allow players to manipulate sounds and visuals in real-time (like laser spotlights for visuals, and tweak the audio like a Korg Kaoss pad).

Alas, while communication with Daft Punk's management was good, the duo (who have both met Q Entertainent creative director, Tetsuya Mizuguchi, and professed to loving Rez) didn't want to use previously released music, and didn't have time to create new music, because of a high pressure schedule to finish the Tron soundtrack. Understandable, but at this point it was obvious that we (Q Entertainment) had to move forward conceptually.

This was a screen of a work-in-progress that was eventually discarded when we created an all-new engine for the game.

While driving to the airport one day with Tetsuya Mizuguchi (who I will refer to as "Miz" from now on; he'd want it that way), he began talking about how he wanted to see a Lumines with flowers and bright colors. I, on the other hand, had been thinking about taking Lumines players on a journey into space and beyond, so I started thinking about how I could reconcile these two vague ideas and make them work together.

It was at this point that I came up with the idea of creating a sort of "concept game" (like a concept album, in musical terms) that would start with a stage of classic, pure Lumines that would be interrupted about three minutes in before all the blocks onscreen exploded in a "big bang". This is where the new Lumines would truly begin, right after surprising players for the first time.

I had a number of different names I was working with, inspired by the concept. Having a name in place really helps me visualize where I'll go with the game concept, so some of the internal names for the concept were Lumines Forever, Lumines: Light Years, and Lumines: Electro Light Orchestra. The last one was actually one that we almost went with before the legal department thought that the band Electric Light Orchestra would give us problems down the road. Ultimately we went with a variation of that name, which turned out to be Lumines Electronic Symphony.

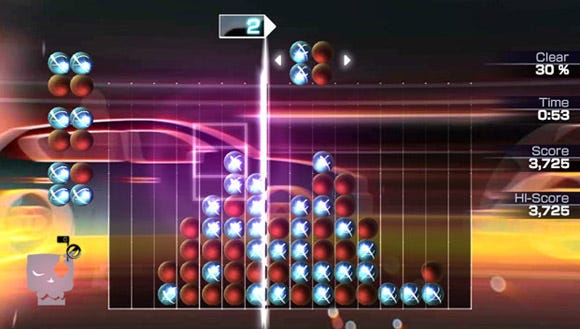

If you look closely at this screen, which clearly shows placeholder fonts and a notable lack of HUD elements, you can see that the blocks aren't perfectly aligned. This was, at the time, one idea we were considering to reflect the physics and impact "engine" we had in mind. We wanted to add velocity and physics to the blocks so that when you dropped a block hard (by pulling down on the D-pad) it would cause the surrounding blocks to shudder from the impact.

This could have had further implications; for example if the blocks were designed as corn kernels, and the alternate blocks were butter cubes, and the skin design was of a frying pan or fire, when you cleared a combo it could create popcorn particle effects. Physics for that skin would then be light and fluffy, allowing the resulting popcorn to pop happily off the screen. Conversely, imagine a skin with ice cubes, water, and snow.

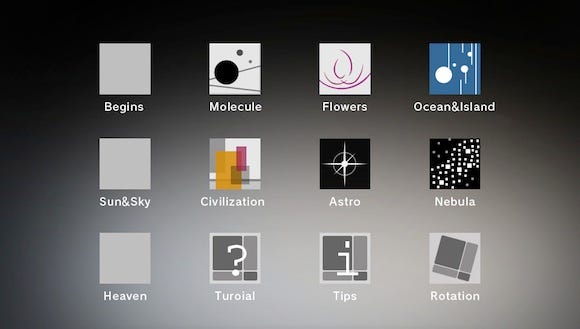

The concept for this variation of Lumines would be to take players on a conceptual journey, with skins arranged and grouped -- post-big bang-effect -- into phases: Molecule, Seed, Flower, Oceans, Sky, Civilization, Astro, Nebula, Heavens, and Beyond. Each phase would consist of three or four songs grouped to fit the vibe -- for example I had selected songs by Towa Tei, Big Audio Dynamite, and The KLF to soundtrack the Civilization phase, to convey the feelings of business, a hectic pace, and the claustrophobia of modern living.

Following Civilization's decline (originally planned to be a series of crumbling, wireframe, 3D Rez-like buildings symbolic of mankind's self-immolation) was the relief offered by the Astro stage which, if I would have had my way, would have surprised people on a number of levels.

First, the song that would have kicked off the Astro phase was Supertramp's "Give A Little Bit". Yes, it's not what anyone would have expected, but it's a great song, and it's uplifting, and it would have been a "Say Anything moment" in the game, one that players would have remembered years down the road. It was meant to send a signal of hope and promise (common Q Entertainment themes), an antidote to the musical rush of "What Time Is Love" that was originally planned to close out the Civilization phase.

The second thing that I was planning to do with the Astro phase was -- since the skin would have been space shuttles slowly exiting the Earth's atmosphere -- reverse gravity. I was dying to hear the reactions of players who, upon entering the Astro phase, suddenly saw their blocks float to the top of the screen.

The gameplay would have remained unaffected, except that blocks would now begin rising from the bottom, as opposed to falling from the top. I thought, "If I can create a moment in puzzle gaming that people still talk about years down the road, I will have accomplished what I set out to do." In the early stages of planning we discussed having blocks come in from all directions to a rotating cluster in the center, but we decided that would no longer feel like Lumines. A lot of things fell by the wayside for not feeling like Lumines -- but I'm getting ahead of myself.

The problem for us was that for a lot of reasons it took us a while to actually get going on would eventually become Electronic Symphony. Part of it was that we kept hoping, internally, that Child of Eden would wrap up development, and that we would then move people over from that to Lumines.

Unfortunately, Child of Eden experienced some challenges during development that required the team to continue working on that project, so it was a few months before we finally decided to bring in not only an external programming team (the excellent Rocket Studios, based in Sapporo -- filled with ex-Hudson veterans, including the original designer of Bomberman), but an external game director as well.

The game director, who will remain unnamed, was not a good fit for the project. I'm not naming him because he's a good guy, but he just wasn't the right man for the project. Whatever you think about Electronic Symphony, had we kept him on board the project, 1) we would never have finished it on time, and 2) I don't think the results would have been satisfactory.

We brought him on the project because he had a lot of game development experience, and his aesthetic sense initially aligned with our internal goals. But it soon became apparent, despite months of trying to synchronize our ideas, that he wanted to make something that looked like an avant-garde Bauhaus (the art movement, not the band) spin on the Lumines formula.

Without consulting the project manager or me, he would make arbitrary decisions like removing some classic elements of the HUD, or other time-proven contributions to the Lumines formula. He would fight over things that weren't important, and then disappear from discussions about things that mattered.

Without going overboard on what he wasn't "getting" about Lumines, I can just say we had to make the difficult decision to shift gears and bring on a different director, which was at the time a very controversial decision, internally, to make, but it ended up being the right move.

Not only did we get the game done on time with our new director, Ubisoft veteran Ding Dong, on board, we created a much more efficient way of working, streamlining the process so we could finish skins faster and with greater, immediate results. If we had to change a color or a texture, we could do it quickly and see the results immediately.

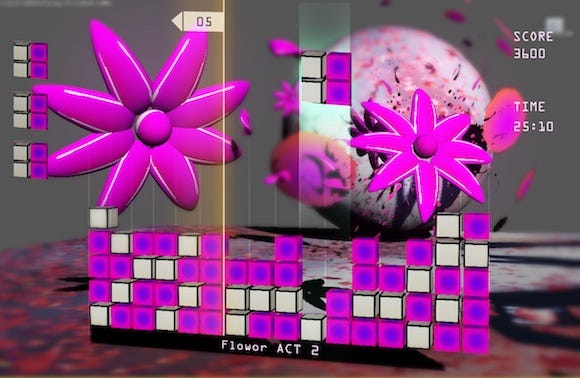

This was another screen from a prototype build of the game that showed a new visual style we were entertaining. The vector blocks at the top of the screen were where we were going to display the upcoming block, and the flower petals were the particle effects generated by clearing blocks. We were also looking at ways to help guide the player in dropping blocks without relying on the explicit grid of past Lumines games.

One example of how the new style differed from the previous director's style was that the old skins were being designed almost completely in code, requiring us to channel every request through the programming team, which was difficult because they were off-site. Any little adjustment (for example, changing flower petals from purple to red) had a big effect on the programming team's workflow, and our artists were sitting around waiting for the results in the meanwhile.

Our new director had the tech team create a template, with a foreground (blocks), a midground (particle effects, like the "COMBO!" counters that appear), and a background (animated movies or 3D effects) where various effects like shaders, opacity, lighting, and other visual details could be tweaked by the artists, instantly.

This made the art flow happen a lot quicker, since not only could we see what was being made, but if we had any feedback -- and we had lots of feedback -- we could see the adjustments as soon as the artists had implemented them, instead of putting in the order to the programmers, and having to wait two or three days to see the results.

The screens that look similar to this were 3D CG animated mock-ups we created to showcase the new visual style we were aiming for once we changed direction. With the rear touchscreen of the Vita, we thought it might also affect not only camera angle but the blocks themselves. Imagine touching the rear screen and seeing the blocks you touched from behind pop up like "pin art". Touching the blocks would also have a musical effect, like running a mallet across a xylophone. That's one of the effects we were considering, but ultimately we couldn't decide on a meaningful way to tie it to the game mechanics, so we dropped the idea for the time being.

The next challenge was the musical elements. With Q Entertainment's experience in a past life on games like Rez, and then eventually on games like Lumines, Meteos Wars, and Every Extend Extra, and finally on Child of Eden, we assigned one of our best synaesthesi' artists --Yoshitaka Asaji -- to handle the correlations between player inputs (pressing buttons) and game feedback (sound effects, musical interaction).

With the help of the sound team, Asaji-san was able to help elevate the level of audiovisual interaction between player and game. I think anyone who has played Lumines Electronic Symphony with a good pair of headphones on will understand where that effort went. Every sound effect in the game was designed to complement the song, so that the player would feel more invested in the game, consciously or subconsciously.

The sound team was able to test these improved synaesthesia techniques on Lumines because I gave them a couple of songs that I was determined to have in the final soundtrack and had them experiment with those. The big challenge, however, was to get the music licensed and in-house in time to let the team edit each song into game-shape.

This is one area where the previous director was seriously holding up the production of the game. While it was a noble goal, he was really adamant about getting multi-track data for each song. This was impractical for a lot of reasons.

As I learned during the course of developing Electronic Symphony, even "just" licensing songs in regular .wav format is tough enough, because you're dealing with an international array of artists, different licensing entities (Japan, France, Belgium, and Germany being especially difficult to negotiate with), and specifics on how you edit music are already big enough challenges.

When you add in trying to get multi-track data from artists, then you need to answer why you need to data, you have to wait for approvals, the licensing costs to mess with the music goes way up, and more often than not you'll just get turned down.

I explained this to the previous director something like 400 times, but once we made the directorial change, it ceased to be an issue. But we were still planning to create as many skins as we could in the time available, and in order to do that we needed to have the songs licensed and in-hand so the editing could begin.

This is personally where the biggest pressure on me lay. Not only did I need to pick 33 or 34 songs that would work well together, and yet skip across the entire spectrum of electronic music, but I also had to have back-ups for each song (minimum five) in case our first choice didn't come through.

So, by the time I was done submitting back-up choices and remembering other great tracks we should try and use, the list had reached about 250 songs. Depending on what songs came in, and what didn't, and what we replaced a rejected song with, I would have to rearrange the tracklist to make sure everything still flowed well.

Another look at our target visual, with more spectacular particle effects. We decided to tone down the 3D perspective shifts, which were originally conceived to work with the Vita's gyroscope and pivot naturally. But we felt it was hard enough for some people to perform well at Lumines without those kinds of perspective shifts, which could prove distracting, so we did away with them in the end.

As I quickly learned, when you're dealing with a body of licensed music this large, with everything hand-picked for maximum effect (as opposed to just licensing a shitload of thrash metal to use as background music for your skateboarding game) the answers take time. In some instances I think we were waiting for four or five months for a response, which really put the artists on hold, because they were designing the game's skins to match the tone, pace, and "color" of the music. When you care about the visual effects as much as we did, this was a priority, and we ultimately had to set a hard deadline for the music to come in before we had to cut our losses and move on with alternatives.

We got most of what we wanted, but we missed out on some songs, either because certain artists generally don't license out their music for video game use (for whatever reason), or because we didn't get sign-off from 1) a songwriter, 2) the song publisher, or 3) the record label. I tried to get artists like Bjork (Alarm Call - Alan Braxe Remix), Orchestral Manoeuvres In the Dark (History Of Modern), Yello (Oh Yeah), Kraftwerk (Neon Lights), Kylie Minogue (Heartstrings), Prefab Sprout (If You Don't Love Me - Future Sound Of London Mix), and others, but for one reason or another couldn't seal the deal on these tracks.

Since the Vita is a touchscreen device we designed the original menu options as an icon-based UI, which eventually evolved into the fractured, staggered look of the final game.

I was also limited to our specific music budget, so I had to mix and match tracks so that we hit our budget cap for the soundtrack. It was surprising to see which artists charged exorbitant rates to use their song, while other artists were surprisingly reasonable (read: affordable) to license. All told it probably took around six months of hard work to nail down the final playlist in Electronic Symphony.

Based on the feedback we received upon announcing the game soundtrack, it seems like the effort was definitely worth it. It's really satisfying to hear feedback from fans who say they like this song or that song best, or were surprised that we included X song or Y song. The best feedback is when I would see a review saying that they don't even like a certain artist, but that in the context of Electronic Symphony it works really well. That's a great feeling.

Speaking of music, one of the things that people asked a lot when Electronic Symphony was first announced was whether we were going to put the song "Shinin'" by Mondo Grosso in the game. If you're not familiar with it, it's the song that begins the original Lumines.

I understand why people kept asking me over the years whether the original Lumines would eventually be sold on PlayStation Network; it's a great game, and "Shinin'" is the perfect song to lead off with. It's an uplifting, gentle, grower of a song that stands up to the repeated listenings anyone playing the O.G. Lumines would endure (since it has a set playlist). But my answer was no, we would not be including in the tracklist, because -- like Daft Punk -- I didn't want the default game to trade in nostalgia, especially when we were on a mission to reboot the series, and with the exception of the game logic and the avatar icons, using old material was pretty much forbidden.

However, that doesn't mean that fan feedback fell on deaf ears. We had lots of DLC plans in store for Electronic Symphony, ranging from a 12-month rollout of new skins, to a six-month episodic release of new skins, modes, and music. The first skin that we had planned as a DLC was a high-definition, all-3D remake of the original "Shinin'" skin, which we figured would please fans craving a digital release of the original game.

Other ideas for DLC were to use the Genki Rockets song "make.believe" in a Child of Eden homage skin, and to try and license Japanese pop group Perfume's awesome track "Polyrhythm". Ultimately these decisions were in the hands of our publisher, who after considering the options, preferred to wait and see how Vita performed at retail before committing to a DLC plan.

Unfortunately, while the Lumines team was well-prepared to create the DLC content during the development of the game, it has now since disbanded and moved on to other projects. While it's conceivable that DLC could still be created for the game, it's unlikely it will happen. I would love to have seen it happen, myself, as there were some great songs and skin ideas that will have to wait for now, but it's out of Q's hands.

Another early version of the game with temporary UI.

Still, it's not every day that a guy gets to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a game soundtrack alone, so I'm not complaining. We got to see the majority of our vision through to completion, and Ubisoft supported us on the technical end in a big way. With a new platform to get to grips with, especially one like PS Vita with its social features like Near, and the PlayStation Network Store interface, it's difficult to develop these things in a vacuum (with no active 3G network to live-test things on).

People have also asked why there's no internet play, and only local ad-hoc play. The simple answer is that we didn't have anyone on the team experienced in competitive 3G or Wi-Fi play, and we didn't have a proper testing environment to run it in. Combine those two elements with the fact that Lumines is a high-speed puzzle game (sorry, but it blows Tetris out of the water, speed-wise), and latency becomes a huge issue.

You can see some abandoned gameplay and UI concepts in this early target movie.

The speed is also why it's really difficult to create a Lumines where touchscreen controls are as effective as D-pad controls (meaning: they're not). The difference between Lumines and a puzzle game that effectively uses touchscreen controls like Drop 7 or Tetris on iPhone is that your blocks aren't dropping at 100mph during endgame levels.

Regarding that whole "big bang" concept for what was once called Lumines Forever -- which would ultimately have looped around until you hit another big bang, and then repeated -- our publisher suggested we discard that idea because it would have been too predictable.

Although we did change the direction of the game -- even entertaining ideas of making this Lumines an urban, graffiti-decorated game at one point -- into what eventually became Lumines Electronic Symphony, the director, Ding, later came to me and said "I think we could have made the Forever concept work." For me that was a small, emotional victory, because I think my instincts were right on that one, and it taught me to trust my instincts moving forward.

Lumines Electronic Symphony (final version)

I'm a gamer, and now a game developer. Before I was a game developer, I spent all day talking about other people's games. I know what I like, and I like what a lot of other people like, and now that I am privileged enough to make the games that people play, who am I to doubt my instincts and inspirations?

I wouldn't call it a mistake, because making any game is a collaboration with a large number of talented, inspired individuals, so you always need to factor in their dreams and desires, too, even if they don't align with your own. But I think you should always follow your heart and try to make what you want to make, and while Electronic Symphony, in my opinion, is something to be proud of, I would certainly like to have seen how Lumines Forever would have turned out.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like