Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What happens when comic artists and indie developers team up to create brand new games? In this look at a Toronto-based Comics vs. Games project, Gamasutra speaks to both sides to find out the results of the collaboration.

August 3, 2012

Author: by Tim Latshaw

Steve Manale admits he is not much of a "game guy." He owns a Wii, and somewhere he might still have an old Gamecube he managed to spill paint on. He works with lines all day, but they're filled with colors, not code.

The Toronto-based artist might still be surprised as anyone that he can now claim co-creatorship of a video game among the accomplishments of his career.

We're No Angels, one of five games made through the Comics vs. Games project, is a collaboration between Manale and veteran game developer Jamie Fristrom. A twin stick shooter with notes of Gauntlet, it pits died-too-young rock stars against Heaven's armies as they try to flee an eternity of private performances for God.

Not only is Manale responsible for the stylized figures of Elvis, Tupac, and other characters that flit about the screen, he came up with the concept for the game itself. Fristrom took the idea and pieces provided and made them move, shaping the gameplay and adding new elements and perspectives as inspiration struck.

It would be somewhat romantic to suggest Manale always had We're No Angels in the back of his mind and wanted to present it as inspiration for a game -- a Doug TenNapel with Earthworm Jim kind of story. The truth is that Manale says he never previously recognized how the style and ideas that inhabit his work in magazines and editorial cartoons could cross over into a more interactive medium.

"I design a lot of comics and have done a lot of comic strips and comic characters over the years," Manale said. "It has never once occurred to me, 'Hey, these characters might translate well into game form.'"

We're No Angels

Part game jam, part social experiment, Comics vs. Games joined independent game developers with comic artists to explore what potential lies in their combined creative powers -- and beyond their comfort zones.

Toronto is a city blessed not only as a hub for independent art and design talent, but also with organizations vested in seeing them grow and succeed.

TIFF Nexus, an initiative of the Toronto Independent Film Festival, started up in September 2011 as a sort of molecular gastronomy lab for multimedia, seeking to identify the elements that make the region's game, digital, film and other artistic communities great and blend them into tasty new concoctions.

"It's designed to equip a new generation of Ontario's storytellers with the network, skills and partners to help us succeed in sort of the rapidly evolving digital media landscape -- this trans-media universe -- that we are living in," said Shane Smith, director of programs for TIFF Nexus.

When the organization approached Miguel Sternberg, co-founder of the Toronto game makers' coalition The Hand Eye Society, to organize a project for its first phase of events, he thought back to the "artxgame" gallery and exhibition he had witnessed in San Francisco three years earlier. Similar developer/artist collaborations could also be made on the opposite side of the continent, he believed, but there appeared to be too few people forming links between the scenes. The indies were being, well, rather independent, and what possible content comic artists could contribute to game design aside from occasional requests for art was going largely untapped.

"Here are these two really interesting creative communities in the same city that are both doing their thing really well," Sternberg said, "but they're not really talking to each other when they could be."

For Comics vs. Games, Sternberg sought out five independent game developers and five comic artists who either lived in or had ties to the Toronto area. Paired into five teams, they were given simple rules: design a game in three months. Multiplayer games were largely encouraged for showcase purposes, but not mandatory. No quotas for gameplay elements or "artistic merit" were established. Whatever teams made were the culmination of their own decisions, leading to some interestingly varied results.

A Comics vs. Games team-up could be compared to asking Houdini and Michelangelo (no, not the turtle) to produce a new illusion. Both sides are obviously great at their individual work and the artist's boundless skills for visualization and imagination can have numerous applications toward the final goal. It's up to Houdini, though, to decide what ideas may actually be possible, and there are still going to be parts where only he knows the technical tricks that make everything work.

So when you normally work alone, keeping the considerations of a partner in mind while their presence simultaneously changes up your routine can be a bit rattling. Christine Love, creator of the visual novel games Digital: A Love Story and Analogue: A Hate Story, teamed up with comic artist Kyla Vanderklugt to create The Mysterious Aphroditus, a Victorian-themed turn-based fighting game whose simple rock, paper, scissors setup is twisted by a bluffing mechanic. Not only is the game style a departure from what Love is known for, but she said working with a partner required relinquishing sole ownership of certain responsibilities and her specific way of doing things.

"It was really weird and a little bit scary just trusting that to Kyla's hands," Love said. "She absolutely delivered, but usually the first thing I do is start with the design work and move from there, so it was just a totally different experience for me."

Vanderklugt, whose art has appeared in anthologies Flight and Spera, said she is more familiar with collaborative work, but also faced similar challenges as Love in creating the art assets more spontaneously, before the team had finalized its game.

"[W]hen I work with script writers on comics, they give me the entire script and I have everything in front of me and I know what to work on, and then my art is kind of like the final stage of the whole project," Vanderklugt said. "When working with Christine, you do the art first, and then she goes into development, and so it was like a big loss of control. I trusted her entirely -- I figured she was going to make an amazing game -- but I was asking myself, 'Is she going to be able to use this art? Is it going to work out?'"

The Mysterious Aphroditus

The hand-drawn characters, from the fighters to the androgynous theater star they are battling for, did come out beautifully. Unfortunately, as the game deadline neared, Love ultimately had to sacrifice roughly 10,000 words of dialog she had written to flesh them out. Where egos could have flared, Love remained cool, deciding the extra text was ultimately detracting from the pace of the gameplay. What descriptions remained combined well with the art, she said, enabling players to fill in the details with their imaginations. The addition of an unabashedly foppish fight announcer also helped.

The jam nature of the project, and specifically its three month limit, may have served as a double-edged sword. Several teams noted they may have been initially overambitious and wished they could have embellished their games with more features before time ran out. On the other hand, the timeframe seemed just long enough to encourage many participants to explore outside their most trusted skill sets.

Fristrom, creator of Schizoid and lead developer on Spider-Man 2, used Comics vs. Games as an opportunity to take the Unity game engine for a test drive while developing We're No Angels.

"Even though I have been making games for so long, the landscape is always constantly changing," Fristrom said. "Five or 10 years ago I would've said you could never make a game like this in this amount of time, but now tools have gotten to the point where you can make fairly amazing stuff in not very much time at all. Things people are able to produce in 48-hour game jams these days are incredible by standards of a few years back."

Fristrom was able to tackle We're No Angels while simultaneously exploring the limits of the game engine. At one point, a bug was found that would make the player's character (Jimi Hendrix and Amy Winehouse are also playable, by the way), literally rise above the playfield. His initial impulse was to fix it, but Fristrom saw the potential benefits of the transcendental hiccup and added it to the game in the form of a drug-based power-up.

Manale loved the addition, awarding a point to the surprises that can arise in the art of programming. Many of the artists said they were mystified by this part of the process, having to place full faith in their partners.

"It was interesting to me, in our final hours, which things were easy to add in Unity and which things were difficult to add to the game," Manale said.

Development tools were not the only change-ups. Some artists also chose to forego their signature styles in favor of alternate routes. Cartoonist and illustrator John Martz worked with developer Jarrad "Farbs" Woods, creator of ROM CHECK FAIL, to create Cumulo Nimblers, a four-player competitive cloud-jumping game. Martz's quirky comic style translates well into the quirkily named Farbs' initial game idea, creating a landscape that is bright, colorful, frenetic, but also pixelated.

Cumulo Nimblers

While Martz has some experience in pixel art, once rendering a cavalcade of Star Trek characters in 8-bit form, the decision to not go with hand-drawn art had a tactical draw.

"I think that limited art style benefited the process because if you wanted to do something -- create an effect or try something out -- [Farbs] could just do it really quickly himself instead of explain what he wanted from me and wait for me to do it," Martz said. "He could sort of easily do it himself with the pixels, so I think it worked out well with the collaboration."

Freelance artist Andy Belanger teamed with organizer Sternberg after one developer dropped out. Discussing concepts over drinks, Belanger was not shy in pushing to make a game based on his new, self-published IP, Black Church, a metal-infused fantasy horror tale revolving around the birth of Dracula and his barbarian parents' fight to keep him from being sacrificed as the embodiment of the Antichrist.

"He explained the storyline to me and I was like, 'Okay, what are the central conflicts here and how can I do something fun that's going to be achievable, that will work with a big audience?'" Sternberg said.

The idea they settled upon was Black Church Brigandage, a game Sternberg describes as a "mashup between Super Smash Bros. and basketball." Players fight 1-on-1 or 2-on-2 on a field of power-ups, swords and explosive barrels, trying to be the first to grab the newborn Antichrist and throw it to their side's goal of safety or destruction. It may well be the first game where you can lay up a baby into a lake of fire.

Black Church Brigandage

Although Belanger created Black Church as a means of establishing his own identity outside of drawing characters for DC and other publishers, he deliberately chose pixel art for Brigandage over his own intricate, illustrative style, wanting to as much of a "game" atmosphere as possible. He said trying to make the game too much like his comic in ways would detract from the crossover appeal.

"I like the idea that when you go from one medium to the other it's going to change quite a bit," Belanger said, "and I think it still has the same spirit of the comic with the gameplay and the sound design. The way you play the game, I think the whole thing has a lot to do with the comic book. It's still there."

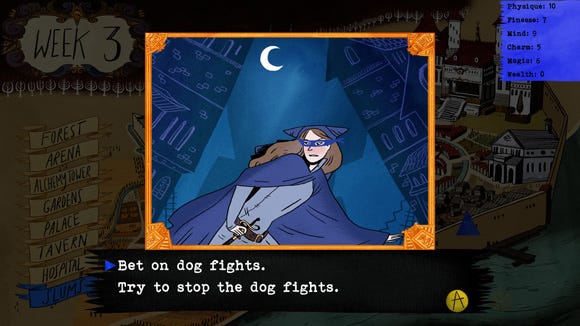

Brigandage is the only game of the five to be directly linked to a comic property, but the most comic-like game is probably The Yawhg. Inspired by choice adventure books and portions of the indie RPG Dungeons of Fayte, one to four players take on roles of different townspeople preparing for the return of a great evil.

With player-driven progression and Emily Carroll's hauntingly folklorist still art, some elements of the overall presentation do harken to an interactive comic book, although Carroll and partner Damian Sommer said the motif was not directly intended.

"The inset panels were the things most reminiscent of comics, and it just happened that not only was it reminiscent of comics, but it also just was easy to make and easy to relay information very simply," Carroll said.

The Yawhg was a cross-Canada collaboration, with Carroll (whose works include His Face All Red) in Vancouver and Sommer in Toronto, but the art did not face as much manipulation as with Cumulo Nimblers. Sommer, who also contributed to the story with Carroll and a few other contributors, was able to place the art as it arrived in Dropbox.

Sommer has also worked as an artist for a game in the past, but he didn't enjoy it. The jam gave him a chance to discover he's much happier as a designer.

"I've never played the designer role, he said. "I was more the designer in this project and the programmer, and I learned through doing this that I'm a lot more comfortable in this role and I actually do like working with people; I just need to be doing this side of it, and not the art side."

The five works of Comics vs. Games tell five different stories of how cross-collaboration doesn't have to follow a set formula and can find success among more styles and genres than one might think. Those stories don't count for much, though, if the games don't find an audience. According to Sternberg, indie game developers and groups must build networks with venues and organizers as much as with other creative talent.

"If you're a musician, you need to learn how to put on live shows," he said. "And that's not just how to perform it; it's also how to organize, how to get the gear from place to place. All of that stuff is what a musician's skill set is, and I think for indie game developers, it's not necessarily the only way to go, but if you really want to evangelize indie games as part of what you do, it's a necessary skill set."

The association with TIFF Nexus provided a foundation of substantial resources and connections, something Sternberg said he felt very lucky to receive.

"I did not realize how much work was involved in the background stuff of making sure that we had a venue booked, that we made sure it was well set up for displaying stuff like monitors and such," he said. "Because there was actually some money behind it, we were able to get some really nice monitors, unlike a lot of indie game stuff, where we're showing all this amazing content, but it's being shown on shitty laptops covered in dust, because they're the same machines people work on all the time."

Springtime showings were held at the Magic Pony contemporary gallery in Toronto and the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. In September, the games are expected to be showcased in some form at the Toronto Independent Film Festival itself -- likely alongside works from other projects and creative jams held by the Nexus within the past year. Visitors to the showings have included members of San Francisco developer Double Fine, some of whom do their own dabbling in comics, and a group of artists from Australia.

Unfortunately, not every region has access to an organization so engaged with independent talent, and even then it can be a struggle for them to provide support. The governmental funding TIFF Nexus received to help operate through its first year and initialize projects like Comics vs. Games has been cut out of the next budget. The organization still plans to go forward however it can with the next phase of projects, though, and Smith is optimistic that the results of Comics vs. Games and other jams will provide evidence of its long-term value as an incubator.

"That is what it is," Smith said, "but we are looking for various other opportunities and I think what Nexus has provided us going out is to say, 'Look what happens. Look what's possible when these different sectors -- industry sectors, different creatives -- come together. Look what we can do and what the potential long-term effects can be.' And we think that's going to help us generate funding from different sources."

The Yawhg

In the meantime, individual efforts are further spreading the games and collaborative concept. The Yawhg and Black Church Brigandage were both submitted to IndieCade, with the latter also entered into the Austin, Texas-based Fantastic Fest. Additionally, Sommer is toying with the idea of turning his engine for The Yawhg into an easy-access story creation engine, given the success others had creating some content for the game. Plans for the other games are still under consideration.

And the ever-ambitious Belanger? He's taking Brigandage and running. He says he'd like to show the game off at conventions and will be hosting a Black Church night with Brigandage tournament during the Thought Bubble comic arts festival in Leeds, England. He has also been in discussion with festival organizers about organizing their own Comics vs. Games-style jam in 2013.

Belanger loves the game, of course, but the other reason for his push is one investors in initiatives like Nexus might want to hear. "From a publishing/marketing situation," he said, "when you have something cross-medium, it's actually really, really awesome."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like