Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Adventure games are filled with their fair share of sleuthing, so why do they often turn into a parody of MacGyver?

Adventure games are filled with their fair share of sleuthing, so why do they often turn into a parody of MacGyver?

Well, gameplay, of course. Browsing the scenery for usable objects -- whether they can be picked up or not, and whether they can be used by themselves or in conjunction with other objects -- is the interactive, cause and effect bit.

macgyver

Way too many designers have asked themselves that very question.Considering how many adventure games revolve around solving mysteries, though, it's surprising that so few of them rely on the player's deductive skills. Instead, the audience is often stuck doing all sorts of illogical things, especially on a micro level. Although there's usually a clear goal, getting there is a matter of figuring out the logistics, not the mystery. When the physical traversal is made possible, bits of exposition follow, and then the cycle repeats.

Now relying on the player's deductive skills can be a big challenge; it's not the most casual concept, it can be difficult to keep all the details of the "big picture" in one's head, and even small discrepancies between the player's conclusions and the designer's intentions can result in an impasse.

Still, it's not impossible.

pwaa-3

Despite the suspenseful music and the serious nature of the crimes, Phoenix Wright's cross-examinations are actually a very casual mechanic.The Ace Attorney series gets around many of these hurdles by staying extremely focused. Whenever a new case begins, you can be pretty positive that your client is innocent and that you possess -- or will eventually attain -- the tools to prove it. Phoenix Wright's internal monologues are also a constant source of clues, and various other characters periodically chime in with advice. Finally, you only have a limited number of inquiries to pursue, and choosing the right path usually boils down to a matter of multiple-choice.

The games still contain traditional adventuring aspects, such as examining crime scenes, but where the series really excels is the court room drama. These segments are based on questioning witnesses, thoroughly investigating evidence, and interacting with the judge and the prosecution. Since the games are very tongue-in-cheek, there's no real preparation involved -- the player is thrown into the fire and learns as he goes.

Of course the lack of prep-work and the continuous stream of new witnesses and evidence isn't exactly realistic, but it works gameplay-wise. It speeds up the intro to the "good parts," i.e., the court room scenes, and compartmentalizes the player's tasks. Witnesses run on a loop, and, until the correct course of action is discovered, the game doesn't progress. Distinct audible cues accompany the player's choices, and once the proper selection is made, a new loop is initiated (often accompanied by new evidence). It's an approach that doesn't require the player to become immediately familiar with all the facets of the scenario, and it serves to ease him through the various segments that compose it.

pwaa-4

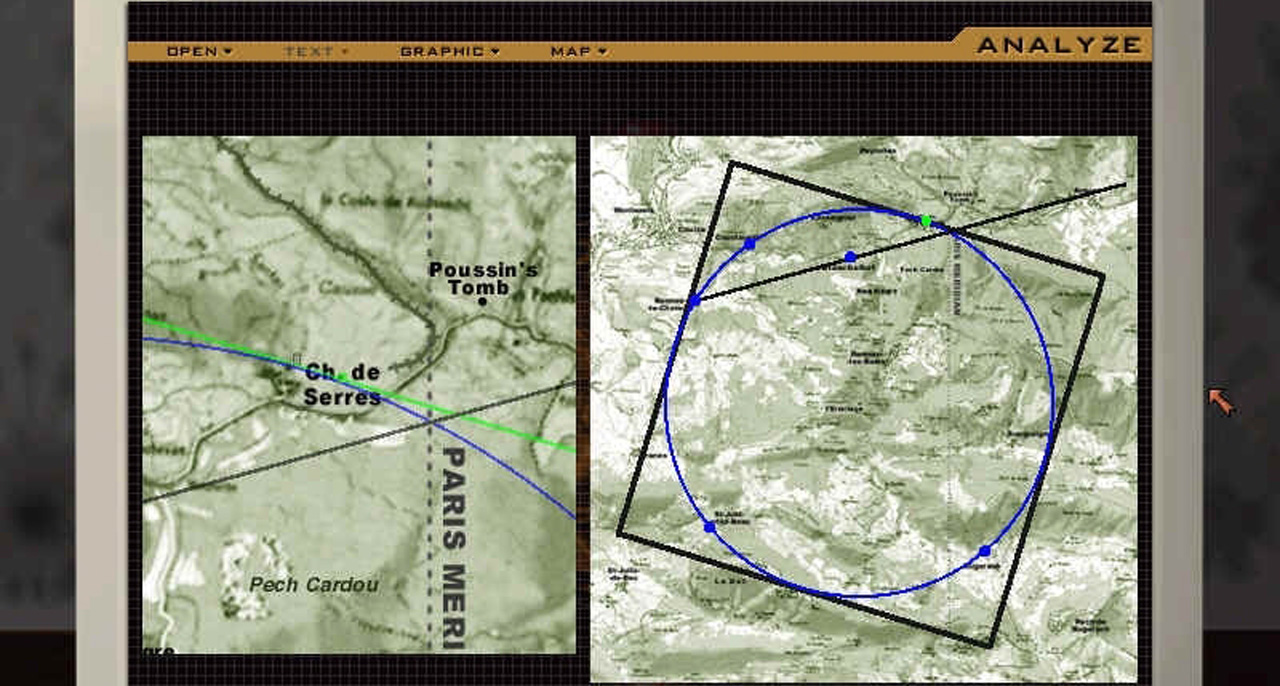

Nailed!Another adventure game that attempts to explicitly tie deductive work into its gameplay is Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned. The two main characters of GK3 have access to an in-game computer, SIDNEY, that keeps track of suspects, fingerprints, memos, notes and maps, and can analyze various files and documents for patterns and hidden symbols. It can also translate languages and plot geometric shapes onto images -- two central mechanics of its renowned Le Serpent Rouge puzzle.

gk3-1

The versatile -- if somewhat unfocused and intimidating -- SIDNEY.SIDNEY works well, but its functionality is a little scattered. The little computer acknowledges correct deductions, but these are fairly open-ended and rely on somewhat subjective interpretations of the designer's intentions. Overall, though, SIDNEY is a good mechanism for gating the game, and it helps to alleviate the MacGyver syndrome.

One more interesting title to throw into the mix is Opera Omnia.

operaomnia-1

Opera Omnia, of cities and men.It's not an adventure game, but it relies on a single interface that's meant to reflect the player's deductions. The concept is simple: connect a series of dots to prove a given hypothesis about population fluctuations. The dots represent cities, and the connections are emigration routes. The diagrams these two elements compose reside on a timeline, and connections can be made or unmade anywhere along the timeline's path.

Since the hypothesis is always stated before a level begins (or at least they were in the stages I played), the end result feels a bit like struggling with office software; you know what you want to do, you just have to figure out how to do it. The concept itself is sound, though, as the interactive diagrams limit the player's choices while constantly providing feedback on his guesses. Once the selected connections match the indicated criteria, a report can be submitted. This provides a clear goal and prevents the player from making incorrect deductions.

Now, how can the lessons of the above three titles be utilized?

Well, let's apply them to a typical premise for an adventure game: a homicide detective story with a unique interface -- a multimedia bulletin board.

bulletinboard

Something like this, except filled with blood samples, audio recordings, bits of surveillance data, etc.The bulletin board is scrollable/zoomable and houses all the notes and evidence of a case. It's a single view of all the vital information required to solve the mystery, and, more importantly, it's the tool that represents the player's deductions. Each piece on the board is manually pinned on and can be connected to any other pieces, with the board automatically refusing illogical connections, e.g., a firearm found at the murder scene cannot be linked to the body if a forensics report -- which is already connected to the victim -- indicates that the cause of death was exsanguination due to numerous laceration wounds.

Forcing the player to manually manipulate the board is empowering and creates a sensation of gradually building a case. Furthermore, a single big-picture view is easy to interact with, and it can also help the player visualize scenarios that he wouldn't have otherwise considered.

Since cases naturally start off with just a couple of bulletin board items, the player is eased into the mystery. The board itself also serves as a gating mechanism, requiring proper connections to be made in order to unlock new inquiries, e.g., once the mother's alibi was proven to be a lie, a search and/or arrest warrant could be procured.

clueboardgame1

Much like Battleship, Clue was actually more about guessing than any deductive work.The actual process of identifying the culprit(s) follows a Clue like approach, i.e., who, where and with what, with an additional when, why and how thrown in to complete the W5H approach. These six categories are associated with each suspect, and they fill up as evidence is amassed and properly connected to the case. An interesting side note to this is that not all the fields need to be completely filled in order to solve a crime. For example, if someone was videotaped committing a murder in a crowded mall, it might not be necessary to figure out their motive in order to prove them guilty. This could open up all sorts of possibilities for not only skipping certain parts of the mystery, but maybe even coming to an incorrect conclusion (it's dangerous gameplay-wise, but could be really interesting for the story). Loose ends could also carry over from one case to another, and unexpected events such as a key witness being murdered -- effectively nullifying his testimony -- would add variety to the goals and the pacing of the game.

Finally, all the pieces on the board could be context sensitive and utilize a hint-dispensing system. This could come in the form of monologues from the player character, or advice from co-workers and other characters.

The bulletin board is a game-specific solution, but its tenets are portable and can be implemented in any number of ways. They're also fairly easy to follow, and should make deductive work accessible for even the most casual gamers.

Radek Koncewicz is the CEO and creative lead of Incubator Games, and also runs the game design blog Significant-Bits.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like