Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What does it take to really implement meaningful co-op in your game? A Virus Named Tom developer Tim Keenan delves into the thorny issue -- discussing the challenges and triumphs of building in the mode for his indie game.

August 24, 2012

Author: by Tim Keenan

What does it take to really implement meaningful co-op in your game? A Virus Named Tom developer Tim Keenan delves into the thorny issue -- discussing the challenges and triumphs of building in the mode for his indie game.

I love playing cooperative games with family and friends. So when I set out to make A Virus Named Tom, I always knew that I would add cooperative play. What I didn't know was how deep the rabbit hole went.

A Virus Named Tom is an action-puzzler where you reconfigure circuits to spread a virus while trying to avoid anti-virus drones. You do this to cause absolute mayhem in a Jetsons-esque future utopia. Your creator, you see, is a bit miffed about being fired after creating said future utopia.

There's a single player campaign, a cooperative campaign (with up to four players), and a vs. mode. Here, I'll talk a bit about what I went through getting the co-op campaign up and running.

"Puzzles aren't cooperative." That's what I was told. You don't see teams of people solving Rubik's Cubes, and you don't see a cooperative mode in Braid (this was also before Portal 2). Cooperation was for killing terrorists, aliens, and zombies.

Solving a complex puzzle is a solitary thing which requires concentration. Cooperation would just be annoying, adding a hindrance. I was also told puzzle games don't need stories. I decided mine was going to have both, because it's my damn game, and that's pretty much the beauty of being an indie dev.

A city infected... by co-op!

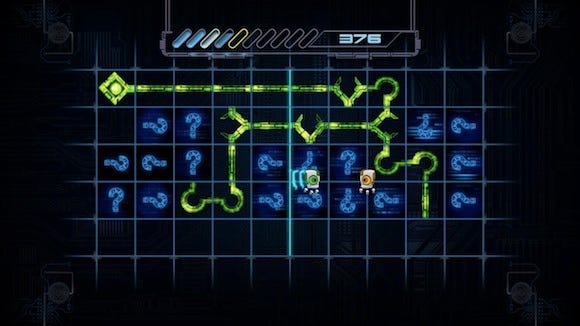

Starting a cooperative puzzle game is easy. Just add more players! The first decisions in A Virus Named Tom were the easy ones. I didn't want splitscreen, or to deal with a shared camera, so the entire circuit would have to sit on a single screen. The circuit has four corners, so each player could start in a nice safe place, off the grid. I think somewhere in the recesses of my brain I thought that I could somehow pull a fast one -- that I could just add three players and say "look, if you want, there's co-op play!"

1, 2, 3, 4 players... Must be co-op!

Initially, I tried to ignore the nagging reminders that it wasn't going to be that easy. Sure, the single player levels were fun for co-op, but some levels that would be great for co-op wouldn't work for single player, and vice versa. Trying to design levels that worked well for one to four players wasn't easy.

It also bothered me that the entire co-op campaign could be defeated with a single player, while players two to four sat idly by. I told myself this was a "feature", because players of different skills could play together without the tension, but this felt hollow as time went on. I wanted players to need each other and affect one another, thereby creating a stronger connection.

The final straw was when I decided to go back to targeting a more core audience. The game started as a core game, targeting gamers that would enjoy a challenge in both puzzle and dexterity. As time went on, and the casual marketplace opened up, I got scarred and started making decisions that would be inclusive of as many player types as possible, therefore skewing more casual-friendly.

Eventually, this just didn't feel right. I knew how I originally intended the game to be played, and didn't want to alter that experience, so I abandoned the casual slant and returned to my original core target demographic. This removed my need to support players of very disparate abilities and required at least two of the players to be fairly core players.

The decision to make co-op in the game a first class citizen was a difficult one, but one I'm very happy with. We're an extremely small team, and this meant doubling the number of levels I would have to design, as well as adding co-op specific features to the game, such as barriers, to force cooperation and roles awarded at the end of each level.

In a way, this made my life easier. Being able to assume at least two players in co-op levels, and only one in single player levels made the level designs much more interesting and fun to create.

This also, however, doubled my informal playtest sessions. To make matters worse, I did not have an office full of employees to test the co-op levels.

The only thing that made co-op possible was being in the IGN Indie Open House, where people like David Rosen (Wolfire Games), Alex Austin (Cryptic Sea), and Justin Woodward (Interabang Entertainment) took time out of their days to run through levels so I could see what worked and what didn't.

We also had lots of other San Francisco Bay Area indies in, all of whom helped me time and time again by playing countless levels. Last but not least were our preorder customers, some of whom were willing to play some of the final levels of the game early to give feedback.

These levels had an even smaller number of playtesters due to their difficulty, and the requirement of having played the previous 40 or so levels to learn all the mechanics.

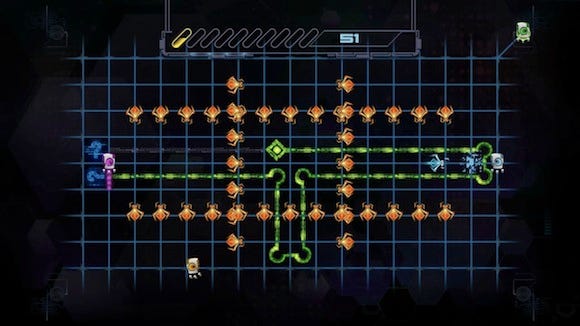

Building barriers to bring viruses together

Watching people play your game is imperative in game design. What's "fun" is simply too complex to not iterate. Listening to feedback is similar, in that you can understand how the player perceives the game and possible problem areas.

This is, of course, a double-edged sword. I don't know that a game designed by committee would result in a great game, because sometimes you have to trust that you have a better holistic understanding of your game. For example, while the player may feel frustration due to a feature, that frustration can be good in the long run if used correctly.

In A Virus Named Tom, time and again in early playtests, players were frustrated by inter-player collisions. They told me that it was simply frustrating to try to solve a puzzle and avoid drones when you got in one another's way. The almost universal suggestion I got for this was to allow players to pass through one another.

Being a game designer is like being in a marriage with your players; you have to listen to everything they say, then pick your battles, and have a good reason for each one you choose to fight. This is a battle I picked. For me, not having player collisions is like turning off friendly fire in a FPS. I made this game cooperative so you would affect one another, for better or worse, warts and all. If there are too many cooks in the kitchen, you have to learn how to work together, like a well-oiled machine.

Allowing players to pass through one another is a step in the wrong direction. It takes the game one step closer to everyone playing the game as an individual, because it means players don't have to consider one another in their movement, which is arguably half of the gameplay in A Virus Named Tom. The added difficulty forces the players to work together, and they usually become a much more efficient unit because of it. They have to communicate -- imagine that!

Not only that, but there's the very real component of griefing! Like friendly fire, half the fun of being able to affect other players is screwing them over, even when it hurts the team, because it's fun! This is why 90 percent of the time my brother and I start an FPS together, one of the first things that happens is one of us will shoot the other. It's just fun!

In the beginning, our collisions simply weren't fun enough. In the early version of A Virus Named Tom, we hadn't put the feedback and emotion into the collision that we have now. We now have a sound, the TOMs bounce off each other, and the TOM that was hit looks really annoyed and curses (in garbled virus-speak) at the other TOM. This addition alone made collisions more enjoyable, and encouraged that sort of griefing.

When players see this they tend to continue to "annoy" their fellow TOMs this way and laugh out loud! We then continued down our dark path by adding a role award for this, and an achievement for bouncing a teammate back into harm's way, killing them. There's plenty of room for deviant behavior in cooperation, and after all, you are a virus.

Intuition left unchecked is arrogant guessing. Intuition is useful to find a starting place, but don't ever fool yourself into believing that you understand anything you haven't seen in action.

My intuition told me the following about cooperative puzzle levels:

I should avoid complex puzzles, as they require a lot of deep thinking, which is best for single player levels

The levels should be larger to avoid too many unintended player collisions

Multiple sources and paths would be best to allow for multiple sub-puzzles to solve

Avoid the combination of difficult puzzles with lots of drones

What I found:

Two out of four ain't bad. Larger boards and multiple sources did help the levels become more enjoyable, but shying away from very difficult puzzles or dexterity did not. Just as in single player, conflict and struggle ties the group together. Players break into roles, talk through complex puzzles, and high five fiercely upon completion.

The key, just as in single player, is to vary up just how much puzzle and how much dexterity were in each level, so that players who enjoyed one over the other would never be more than a level or two away from a level they liked, and generally the pacing kept things interesting.

A co-op level with challening dexerity requirements

What else I found:

Busy work is good for co-op, not so much for single player. What I mean by this is that when playing cooperatively, having a board full of lots of pieces that need to be turned is kind of fun. Seeing how quickly a circuit can be re-configured when pooling resources is pretty cool. When playing single player, it simply feels like busy work, since no one else is whistling with you while you work.

You can have harder levels in co-op. Initially the levels in co-op and single player were the same, and therefore the benefit to bringing a friend is that you can solve the levels faster with more minds/thumbs. However, when I decided to have entirely separate levels for co-op, I noticed that not only did you have more minds, but a greater chance of one of the team members saying "one more time" on a particularly difficult level.

The progression through that level felt faster as well, because there was less of a chance of getting stuck down one rabbit hole, since each mind on the team worked differently. Ultimately, I made those levels more difficult because I felt that I could, and I'm a bastard like that.

When I first watched groups of people play the game, it became clear that everyone couldn't be the puzzle solver. Nowhere was this more evident than in the first level. I originally had the same levels for both single player and multiplayer, and the first level was a simple straight line with one circuit piece turned the wrong way. Every player would rush toward the piece to turn and collide with one another.

While it was absolutely hilarious to watch the TOMs all bounce off one another, get their angry face on, and curse at one another, it was clear that that would only be amusing for a few levels. Eventually I needed to solve the problem of everyone trying to solve the lead edge of the infection by turning the next piece.

One of the ways we did this was with roles. I momentarily debated giving different TOMs different abilities, like classes. I didn't like this, because I'd be asking people to choose a class based off no prior knowledge (In an FPS, you'd have context for what a sniper character would be, but there weren't many class-based puzzle games), and I also wanted people to be able to dynamically shift their roles based on the need. So what we did was give all of the TOMs various skills, and then put players in a pressure cooker, where they couldn't win if they all did the same thing.

I also believe in attacking a problem in multiple ways, so in addition to making it necessary for players to take on various roles, we added what we called a "role results screen" where players got awards for being the best or worst at a particular role. This not only underscored the idea for players to take on different roles, but added a slice of competition, and even some mocking for players that weren't pulling their weight. We tried to make the award icons a bit ridiculous to keep it fun, and none of the stats held over from level to level. I believe players are ultimately social, and sometimes all you need to do is give them something to banter about.

It's where I do my best thinking, anyway

One thing I worried a lot about was making a local co-op game for PC. Admittedly, when we started A Virus Named Tom, the core target was console and couch play. When we realized we didn't have the money for online play I knew that, despite being a 10 dollar game, we were going to get a lot of grief for asking PC gamers to crowd around their monitors.

While this is true to an extent, the number of players that share my love of couch co-op surprised me. Each year it gets easier and easier to plug your computer into a TV, and connect some game pads. Sitting next to your fellow player is something amazing, and sometimes you forget what that's like. While I understand for many it may not be an option, for those that can, I think we need to support games that make this part of their design by voicing our approval. I know I appreciate all those that have done so for A Virus Named Tom.

While making co-op a first class citizen in A Virus Named Tom was difficult with a small team, I have to say there was nothing nearly as rewarding as watching a group of players taking on the challenge of those cooperative levels. To hear them ribbing one another's failures, bickering over a solution, laughing over griefing one another, and the elation after a hard fought victory, was nothing short of moving. It's as if each additional player multiplies my enjoyment of watching the process.

There's a strong temptation to create a purely single player game for our next title because of the sheer amount of work required by a small team to add legitimate cooperative play, but I honestly don't know if I can give up that feeling of standing behind a group of players and seeing the genuine interactions you've caused. Somewhat infectious, you might say.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like