Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Veteran game devs Lori and Corey Cole (Quest for Glory series) open up about how they designed their new game, Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption, with an emphasis on player agency and role-playing.

“When we’re designing a game, it’s all about ‘What does the player want to do?’ What will they try?” says Lori Cole when speaking of the design ideas that went into Transolar Games' Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption, as well as her many years working in adventure and role-playing games.

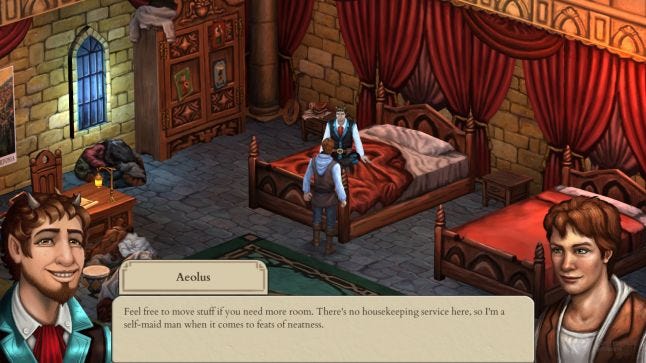

Created by Lori and Corey Cole, designers of the Quest for Glory series, Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption casts the player as Shawn O’Connor, a man striving to be Rogue of the Year while keeping up with university classes, exploring a haunted castle, making friends and foes, dealing with monsters, and solving devious puzzles.

“We think of these things as problems, rather than puzzles," says Corey Cole. "We don’t want to say there is only one way past this and you have to guess what’s on our minds and get it. We know players are going to use every tool at their disposal to try to find ways to solve the thing, and we try to make it so that as many reasonable things as possible work.”

This freedom to attack problems in a variety of ways offers a refreshing means of working through an adventure game, allowing players to feel like they’re using their character and skills to solve puzzles rather than finding out the single solution the developer put in.

Curious devs should note that this attitude, where the player’s creativity is emphasized in a large world filled with solutions, owes much to the developers’ experiences with another game that focuses on player creativity: Dungeons and Dragons.

With an emphasis on world-building and role-playing, the Coles feel they've created a game where the player can settle into a character within the world, looking for how they would solve its problems rather than guessing how the developer’s intended them to, tapping into that infinite possibility pen and paper role-playing games often offer, giving players a special, personal way of interacting with their game world.

We always tried to make that experience that we loved in D&D in our games. The ability to do things, to try things that you never have – that’s what games and D&D were doing for us."

“We always tried to make that experience that we loved in D&D in our games. The ability to do things, to try things that you never have – that’s what games and D&D were doing for us,” says Lori Cole.

Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption looks to make the player feel like they're solving its problems using their own plans. While, admittedly, these solutions all have to be put in place by the developers, there is no problem in the game that only has a single solution. There are means for the player to figure out, based on the kind of character they’ve built and what they’ve done, a solution to their current quandary.

Part of this comes from the developers’ work in creating an expansive world for their players to explore, and various things for them to do, implying an openness to the action. Not only does this give the player a feeling of being in a grand world filled with possibility, but it also implies, by the sheer scope of what the player can do, that there’s no reason to feel trapped as there are other activities and means the player can try out to get past a problem, or other things they can do if they just need to walk away from it for a while.

“Quest for Glory was an adventure/role-playing game. We’ve actually brought in a third category for Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption. It’s an adventure/role-playing/simulation game. We have the day/night cycle where certain things happen at certain hours of the day. You need to get to classes on time and you need to get to supper. You need to get to bed at night,” says Corey Cole. “The player has to balance trying to pass their tests while being a real adventurer and a hero.”

“From the role-playing side, we brought in a Reputation system that lets you see how many friends your making and what your enemies’ statuses are. You can work to get as many friends as possible in the game if that’s the sort of thing you enjoy doing. We have a character sheet where you can find equipment, finding some goofy-looking gear for him to wear if you want to,” says Lori Cole.

Players are free to skulk through the castle, cracking locks and finding its secrets. They can fight monsters in the dungeons. Gather traps they can use to make combat a little easier, or seek out hidden items that will help them avoid fights altogether. It’s not even just a focus on pure gameplay rewards, either, with the Coles adding a great deal of humor and creative flavor texts for players to find.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“Humor was always a hallmark of Quest for Glory, and we wanted to make sure we brought that back as well,” says Corey Cole. “This is a dramatic game, but also a comedic game. There’s a lot of puns and a lot of humor, especially with incidental stuff. If people are curious and they’re the explorer type of personality who click on everything and try everything in the game, they’ll be rewarded for that. Not so much in getting gold and glory, but in having fun reading all the little Easter eggs and messages peppered throughout the game.”

This was all key to that role-playing D&D feel. Players would be given a world to interact with, and then it would be up to them to figure out what they wanted to do within it. A player in a role-playing campaign might not be as interested in saving the world as they are in setting up a market stall and selling codpieces. They may want to learn the ways of the forest or study a goblin clan. It is about letting the player guide the game and making their own story out of the worlds the developer creates, a spirit which is captured by all of these play elements in Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption. The player can choose how to spend their time, limited as it is.

“The player is constantly pressured by only having a limited number of hours and days to do things. It’s a very deliberate game design that forces players to really think about how they want to allocate their limited amount of time,” says Corey Cole.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

It doesn’t hurt that, in making the player feel like they’re in a world open with possibility, it also enriched the game’s world and what made it special, allowing Lori Cole to create a realized place with her writing. “I’m an artist, and that means I have to write a game just the way I want it. That meant being able to do everything I wanted in the game. Trying to make it exciting and fun while having a variety of things that really made it special.”

“I’m more fond of role-playing games than I am of adventure games because the latter tend to have puzzles that snare you. If you can’t figure out the puzzle, you can’t actually continue to play the game. Our whole theory and philosophy for making Quest for Glory and Hero-U has been to make it fun and not have a thing that stops the player from going on and enjoying things. So, what we’re trying to do is bring in more of the roleplaying aspects so that you’ve always got something else you can do. If you can’t get through the secret door because you can’t figure out the stupid puzzle, then maybe you’ll leave it for another (in-game) day or ask another character how to get past it,” she continues.

By creating so many things to do, so many systems to deal with dangers and puzzles, and even just reams of text and descriptions for players to work through, the emphasis is placed on what the player wishes to do within the world, rather than a linear path through a storyline. It’s not the player working through a narrative, but a player creating their own narrative within the world, drawing upon that crucial difference that often exists between video games and pen and paper role-playing ones.

“We want the player to create the story through the way they play,” says Lori Cole.

The issue with creating multiple solutions for players to use in a given situation is much more complicated in a video game than on paper, though. A skilled dungeon master can alter the path of a game of D&D on the fly, allowing players to find their own paths through the story when they move completely off the rails from a planned campaign. A preprogrammed game cannot suddenly change its programming to suit another solution to an in-game problem or cater to players working counter to how it was built, though, creating a daunting problem for developers who wish to leave solutions more open to creativity.

“As an experienced dungeon master, you come up with all of these ideas on what the players should do, and they come up with something else. It’s always that way. The trick with designing a computer game is that you can’t possibly cover everything the player will come up with, but you have to give them the feeling that they thought about something and came up with a solution that maybe you didn’t think of, and then let the game go with that,” says Lori Cole.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“Although you did have to think of that, and you did have to prepare for it so that they could do something different,” she continues. “You have to really work hard to make the player feel like they’re in control. It’s a puzzle-solving game in itself. As the designer, you’re really coming up with these problems, and then you also have to come up with multiple ways to handle that problem from all sorts of approaches. It’s always a challenge, and it’s a lot like playing a game when you’re making one. You’re really trying to outthink yourself, and trying to find a way to get these wild ideas in a manageable form so you can get the game done sometime.”

It would be extremely challenging to create a game with all of the flexibility of a pen-and-paper RPG, but by having a handful of available solutions, they can still capture that feeling that the player is solving problems through their creativity. As an example, a monster can be made a lot less troubling should the player take the time to get to know them, talking to them and learning about their fear of a certain animal.

“During a silly session while we were throwing out goofy ideas, somewhere along the lines we came up with Protection from Panda items. We have several of those in-game. We have a monster in the game who is terrified of pandas, even though there are no actual pandas in the game. You can only appease him by trading him a Protection from Panda item or fighting him,” says Corey Cole.

Even combat can be made more open to interpretation, offering various fighting styles to use on monsters so that it becomes more about how the player approaches danger. “We provide tools so that players can figure out how to use them to solve problems. In combat, there’s a monster in your way. That’s a problem,” says Corey Cole.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“Your character is not a superior warrior. He’s a rogue. It can be better to use the sneaky techniques at his disposal. We’ve got sleeping powder, traps, healing potions. You can buff yourself going in with agility pills and fitness pills. You can make your weapon temporarily magical. There are all these techniques available, and we don’t prescribe to only one given way to get past a monster,” he continues.

Combat is so open to players coming up with their own solutions that it can be avoided in its entirety. “We made it actually possible, although it is by far the hardest problem in the game, to play through all of Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption and never fight in combat.”

"That’s part of the motivation to play. To see what you can find – to find new things and test new things out."

These combat options, as well as having other areas the player can explore or activities players can take part of, work within the systems of games to allow for that feeling of discovery, storytelling, and creativity that makes pen-and-paper role-playing so compelling. It gives the player that sense that they’re carving their way through the game’s problems in a manner of their choosing, and turns them into agents of the story rather than moving through a narrative on rails.

This is what draws the Coles to add so many play elements and pieces of text to their games, creating that feeling of being a part of a realized place where the player has an effect. Would be colossally challenging to create a game that could handle anything the player wants to do, but there area realistic ways of making the world feel grand and the player to feel that they have choices within it. Through offering options on what to do, multiple ways to realistically handle problems, and even just hints of a full world beyond the game, it creates that feeling of involvement within the player.

“That’s part of the motivation to play. To see what you can find – to find new things and test new things out," concludes Lori Cole. "The magic of a game is that you can’t lose as long as you play. You can’t make a mistake that you can’t undo or can’t find a way around."

You May Also Like