Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this sponsored feature, Umbra Software discusses the pros and cons of various methods currently being used for occlusion culling and explains its own automated occlusion culling system that can take any type of polygon soup as input.

March 6, 2012

Sponsored by Umbra Software

Author: by Umbra Software

[In this sponsored feature, Umbra Software discusses the pros and cons of various methods currently being used for occlusion culling and explains its own automated occlusion culling system that can take any type of polygon soup as input.

Founded in 2006, Umbra Software is a Finnish middleware company specializing in graphics rendering technology. The company was spun off from Hybrid Graphics when it acquired the dPVS system and continued its development into what became Umbra occlusion culling middleware. The core engineering team at Umbra has worked in the field of occlusion culling since 2000. Their technology is being used in games from developers such as Bungie, BioWare, 38 Studios, Square Enix Co., IO Interactive, Remedy, Specular Interactive and many others who have helped shape the technology.]

Watch a video of Umbra 3. Contact Umbra here.

When rendering 3D world views in a game, resources spent in processing elements that are invisible to the player are inevitably wasted. These resources could be better used to increase the visual complexity of the visible elements or to decrease the time taken to produce a frame. For this, we must identify the objects that are not visible to the player.

Determining the set of elements that are not visible from a particular viewpoint, due to being occluded by elements in front of them, is known as occlusion culling.

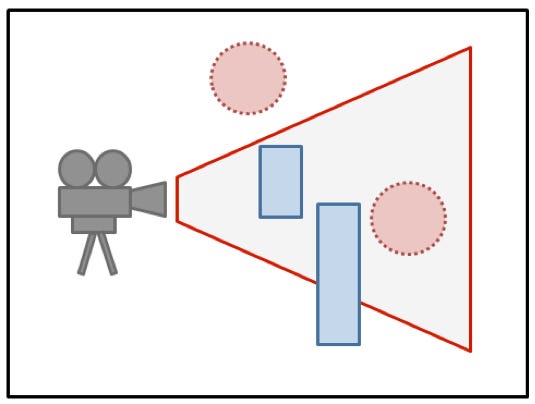

Image 1: The basics of occlusion culling. The red circle in the view frustum is not visible to the camera, because it is being occluded by the blue rectangles. The upper red circle, for its part, is not visible, because it does not intersect the view frustum.

In real-time interactive applications, occlusion culling is traditionally used as a rendering optimization technique. It allows the production of frames at a rate that creates the perception of continuous movement. There is, however, a variety of uses for visibility information outside of pure rendering. Knowing whether an object is currently visible or not can be used to:

Influence AI behavior

Simplify or disable physics simulation and animation

Reduce the amount of network traffic required to replicate player positions across the network.

When assessing the value of an occlusion culling system, some of the desirable properties are:

It works automatically and universally

Ideally, an occlusion culling system automatically works with any kind of 3D content, from simple object viewers to massive virtual worlds, and requires no manual work from the artists building and modeling the game world. Furthermore, the system should not pose restrictions on the creativity of the artist. Finally, the system should not depend on any specific hardware features, rendering conventions, or authoring methods or tools.

It is conservatively correct

A system that sometimes determines fully or partially visible objects to be fully occluded, is bound to produce rendering artifacts, whereas a system that sometimes reports fully occluded objects to be visible can, usually, generate the correct visual output.

It adds value

For rendering purposes, occlusion culling must be judged against the reference solution of simply rendering everything in the view frustum. For example, a sports game based in an arena where only a little of the total amount of content is occluded at any given time, is not a good candidate for an occlusion system. The effort put into determining occlusion is wasted as no benefit can be gained. However, when visual complexity and a lot of detail in complex 3D worlds are required, the benefits of an occlusion system begin to increase significantly.

In this article, we first briefly introduce the problem domain and look at the popular methods currently being used for occlusion culling, highlighting the challenges they pose in the context of game development. Then, we describe a novel approach to occlusion culling, developed to satisfy the needs of our partners and clients building the next generation of game engines.

This approach is called the Umbra 3 occlusion culling system.

The roots of occlusion culling in 3D graphics lie in hidden line and hidden surface determination algorithms. These algorithms are necessary to produce visually correct images of 2D projections in a 3D space.

The problem is simple enough to grasp -- out of the rays of light travelling from surfaces in the world towards your eye, only the ones that do not run into obstacles on the way will contribute to the final image. This is an instance of the visibility problem and the formulation readily suggests one possible solution for 3D rendering: we could simply trace light rays back from the eye and find the first surface that each ray intersects with.

All modern polygon rasterizing renderers, both software and hardware, track the smallest distance value per sample and only update the sample when encountering a distance value smaller than the current minimum. This solution is known as Z-buffering or depth buffering, for the additional buffer of Z values maintained. Given the amount of work already done for 2D projection and raster sampling, the computation of the Z component is relatively cheap and guarantees the correct visual result. Computation can be reduced by introducing primitives in a front-to-back order: rendering the nearest primitive for a given sample first means that the contribution of all other primitives along the same ray can be rejected by the depth test and, therefore, any computation for determining the final output of a hidden sample, such as interpolating vertex attributes or doing texture lookups, can be skipped.

Z-buffering with a front-to-back primitive rendering order gets pretty close to the ideal of only calculating a single value for each output pixel. Unfortunately, the culling takes place very late in the rendering pipeline of a 3D game application. At the point where the renderer rejects an occluded sample, the sample has gone through several stages of the graphics pipeline from feeding the input geometry and dependent resources to the GPU for per-vertex processing, triangle setup and rasterization. Methods exist for early Z-culling in the rendering pipeline, but ultimately the largest computation savings are obtained by culling the largest renderable entities of the engine prior to feeding them into the rendering subsystem.

Traditionally, occlusion culling refers to this type of rendering optimization.

Most runtime occlusion culling strategies tell if an object will be visible by doing the equivalent of per-sample depth testing for the transformed bounds of potentially occluded individual objects or object hierarchies. The challenge is to build a depth buffer estimate of the view before the actual rendering takes place.

One widely used solution is to use a separate depth rendering pass or the depth results of a previous frame on the GPU, and use occlusion queries. An occlusion query returns the number of samples that potentially pass the depth test, without actually processing or writing pixel values. The challenge with this approach is the synchronization between the CPU and GPU required to transfer the test data and to obtain the occlusion information. In practice, it is virtually impossible to use this approach for anything else than rendering optimization.

The upside is that there is no extra work done in generating the depth buffer and it represents the exact final image for any kind of occluder geometry. To allow the CPU and GPU to operate asynchronously, and to minimize the traffic between them, these systems typically use the previous frame depth buffer results and, therefore, cannot guarantee conservative culling.

An alternative is to rasterize a simplified representation of the occluder geometry into a smaller resolution depth buffer on the CPU. To obtain conservative culling, the geometry must not exceed the raster coverage of the real result. Usually the content artists manually create these occlusion models, side-by-side with the real models.

When the runtime cost of early depth buffer generation and occlusion testing is not feasible and the occluder geometry is mostly static, a viable alternative is to determine and store the visibility relations between view cells and renderable entities in a preprocess phase. The set of entities determined visible from a view cell is known as the potentially visible set. The runtime operation involves simply finding the view cell of the current camera location and looking up the set from memory. In simple cases, the visibility relations can be constructed manually by the level designer, but the usual method is to sample the visibility from a view cell either by ray casting or rasterizing in all directions. It is difficult to guarantee conservative culling in either case. By increasing the number of samples per view cell, the amount of error can be managed at the expense of time required for the computation. In addition to static target objects, volumetric visibility information in the form of target cells can be stored in the set for the ability to also cull non-static entities.

The generation of potentially visible sets can be automated, but a large amount of data must be generated to obtain reasonable culling results. The sampling time in the preprocess phase slows down the content iteration cycle and the sheer amount of data for representing the visibility relations can quickly become unmanageable. This is particularly so because visibility relations are global in nature; a small change in the occluder geometry can cause changes in visibility relations far away and on all sides of the original change and, therefore, necessitate recomputing the potentially visible set of a large area.

A third category of occlusion culling systems is based on dividing the static game world into cells and capturing the visibility between adjacent cells with 2D portals. The runtime operation is to find the cell where the camera is and to traverse the formed cell graph, restricting the visibility on the way by clipping the view frustum to the portals traversed. Objects are assigned to cells in a preprocessing phase and their visibility is determined upon by visiting the cell that they are in. This approach works best when there are obvious hot spots in the world for the level designer to place portals at, such as doors or windows connecting rooms in an indoor setting.

The portals-and-cells data is a simplified occlusion model of the world that stores non-occluders and their connectivity, instead of occluders. While accurate and conservative occlusion results can be obtained with a relatively lightweight runtime cost, the work of manually placing cells and portals is very labor intensive, error prone and it dramatically increases the cost of content modification.

The Umbra 3 occlusion culling system was designed to overcome the challenges described in the previous chapters.

Umbra 3 is based on the idea of transforming a 3D world from its detailed artist created polygon representation into a simplified one. The transformation focuses on capturing the essential occlusion properties while ignoring information on details having no or little relevance in the occlusion culling process. This approach resembles the manually constructed portals-and-cells graph. However, the occlusion model used by Umbra 3 is an automatically generated portals-and-cells graph.

Traditionally, the game worlds where portal culling is successfully employed have been crafted to allow a small number of portals to capture coarse-level occlusion information: empty spaces connected by narrow passages, with most of the connectivity taking place on or near the ground plane. A generic solution cannot make such assumptions about the world and must work with arbitrarily complicated topologies in all three dimensions. A much larger number of cells and portals are required to capture the occlusion of large outdoor areas having individual occluding features.

Umbra 3 consists of two components:

The Optimizer

The Optimizer is integrated into the game editor in the pre-processing phase. It takes as input any type of polygon soup and discretizes the entire scene into voxels to generate view cells. The view cells are then connected through portals. The portals-and-cells graph data is stored into an optimized data structure that is then accessed at runtime.

The Runtime component

The runtime component rasterizes a software depth buffer that is used to test visibility. It allows a large number of dynamic object tests per frame, with very little computation cost. The accuracy of the algorithm is near that of hardware occlusion queries, but – being a purely a software implementation – is free of any synchronization and portability issues typical to hardware-based occlusion culling.

A conceptual Umbra 3 architecture is depicted in the figure below:

The engineering challenges for the automatically generated portals-and-cells graph can be summarized as follows:

A random polygon soup must be turned into a representative portals-and-cells graph in a fashion that allows controlling the graph size versus occlusion granularity.

An effective runtime culling method is required. It must use the portals-and-cells graph and be able to cope with a relatively large number of portals. Furthermore, it must yield conservative culling results in fixed or limited memory and do it fast enough not to become a bottleneck in a minimal occlusion scenario.

The following two chapters describe solutions to these two challenges as implemented in the Umbra 3 occlusion culling system.

On a high level, the graph for a 3D scene is generated by building a raw, evenly distributed initial portal graph. This graph is progressively simplified by removing data that has little contribution to the overall occlusion. The input occluder meshes are only used in the initial cell generation phase to determine whether an individual voxel, or an axis aligned box, is to be considered solid or empty.

The voxelization allows the algorithm to be independent of geometric complexity; the fact that the result only needs to conservatively approximate the real geometry makes this possible.

The initial graph is defined by first subdividing the scene geometry into an axis-aligned grid. The initial grid node size is chosen to match the granularity at which we want to sample the scene occlusion features. Next, we further subdivide the geometry into voxels that are tagged as either solid or empty, based on intersecting the voxel with the geometry.

The voxels are used to find non-connected regions within the cube by flood-filling empty voxels, that is, by recursively grouping neighboring empty voxels together. The empty voxel sets are the initial candidate cells for our graph. For each such empty voxel group, we find the intersection with the cube faces and store the axis-aligned bounds of the intersection as a portal rectangle. To connect the initial cells into a graph, the portal is matched to a neighbor portal generated on the other side of the cube face.

Image 2: Initial cell generation. The first image from the left represents a 2D cross-section of a grid node with a detailed geometry in it. In the second figure, the geometry is approximated with solid voxels. In the third figure, empty voxels are flood-filled into three distinct areas that form the initial view cells. Portals are generated where the empty voxels intersect the cube faces.

The virtue of using a discrete volumetric representation of the geometry should be apparent. Intersecting arbitrary polygon data with axis aligned boxes can be done in a numerically robust fashion and, once the voxels are formed, the algorithm is independent of the complexity of the input data and only needs to deal with a simple integer grid. As we are after a conservative occlusion representation, we do not need to follow the geometry exactly, as long as we err to the conservative side.

The single exception to this method is the connectivity determination within the grid node. A hole in the mesh data smaller than the selected voxel size will not be captured by a path of empty voxels and will not contribute to connectivity. Fortunately, small isolated see-through holes are relatively uncommon and often unintended in games.

If we, at this point, have information on static target objects, we can proceed to similarly voxelize their geometry and assign objects to our initial cells by finding the cell where the neighboring empty voxels belong to. Naturally, if the same geometry is to be used both as an occluder and a static target object, we can save half of the work.

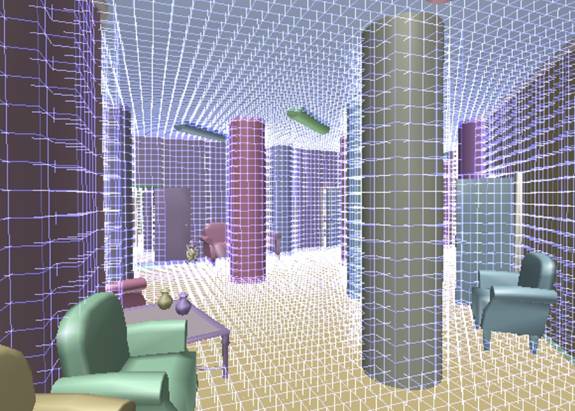

Image 3: Solid occluder voxels, shown as wireframe cubes. Note that some objects are not considered for occlusion.

If we can find the portal that has the smallest occlusion value in our portals-and-cells graph, we can remove the portal by combining the cells that the portal connects together. This method forms a simplified graph that minimizes the overall occlusion information lost. Proceeding iteratively up to a threshold portal occlusion score, or to a fixed memory budget, we can control the cost-benefit ratio of the final graph.

Optimal graph simplification by grouping together the two cells connected by the portal that have the worst global occlusion value would require prohibitively expensive global graph analysis, as visibility essentially is a global attribute. However, local heuristics can be applied to quickly trim the most useless portals out of the graph. The simplification can be done in a hierarchical fashion, decreasing the portal occlusion threshold value as we proceed upwards in the hierarchy to larger scopes. At every new level of the hierarchy, we connect the external portals of the neighboring volumes and run the simplification for the newly formed combined graph.

The hierarchical simplification also provides the opportunity to output level-of-detail versions of the occlusion data. The runtime algorithm can use these outputs to choose the level of occlusion used, based on the distance from the viewpoint.

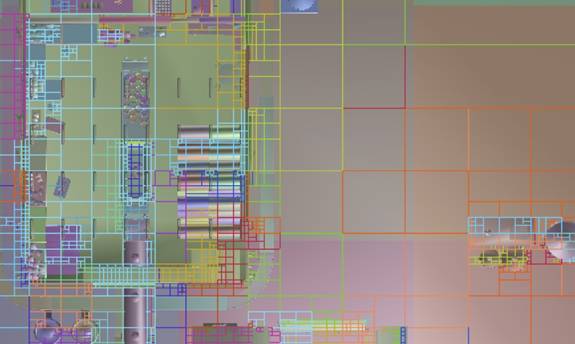

Image 4: A birds-eye view of generated cells in a game world that contains both indoor (on the left) and outdoor (on the right) areas

The portals-and-cells graphs can get extremely complex. The final game cells formed by division into connected voxel groups, and subsequent cell grouping, are no longer easily captured by simple geometric shapes, and storing the complete voxel structure of even a small scene is impractical. To use the portals-and-cells graph for runtime culling, another data structure is required to accurately locate the cell corresponding to the camera position in the graph. This data structure is called the view tree.

In a nutshell, the view tree is built as follows:

Two adjacent empty voxels belonging to the same cell can be collapsed together, as storing them separately does not add any information. Large empty areas can be collapsed to axis-aligned entities in the view tree.

In game applications, the camera is not allowed to be located arbitrarily close to geometry. This ensures that the near clipping plane cannot intersect geometry, as that would cause unwanted rendering results. Therefore, we can collapse neighboring solid voxels, and even empty voxels, belonging to separate cells as long as the size of the resulting element does not exceed the camera collision radius.

Finally, we can identify and simplify voxel groups residing in volumes where the camera is not allowed to be in. This includes cells formed inside walls and below the terrain.

Apart from adjusting parameters for voxelization, the process of portal generation is automatic. It can, however, take some time to finish. This is inconvenient from the perspective of content iteration and it wastes valuable artist and designer time. Memory usage is also a concern. Unsimplified, high resolution voxelization can consume gigabytes of memory.

Umbra 3 avoids this problem by dividing the world into spatial computation units, tiles, which can be computed independently from each other. The world can then be computed tile by tile in a parallel or distributed fashion. Only the currently processed set of tiles requires memory for high resolution voxel representation.

As the portal generation process is deterministic, computation results for a tile can also be stored by hashed input. This approach supports incremental changes, where only the updated part of a scene needs to be recomputed. The results can also be shared over the network. At runtime, the visibility data can be streamed by tile.

The other component of the Umbra 3 solution is a runtime occlusion culling algorithm. This algorithm uses the simplified occlusion model to determine visibility from a camera view.

The runtime culling algorithm needs to be fast -- the full operation must be completed in the order of a few milliseconds -- to meet the requirement of adding value in a game running at 60 frames per second.

As the amount of processed portal graph data can be significant, one key consideration in the algorithm design is the data access and caching pattern. This is especially the case with hardware architectures optimized for streaming parallel data, such as the Cell processor in PlayStation 3.

The automatically generated portals-and-cells graph does not fundamentally differ from a traditional hand-generated graph. Therefore, we could readily use the traditional portal culling algorithm of recursively traversing the graph while clipping the view frustum to the portals entered. This kind of traversal must, however, visit each cell once for every visible path leading into it. In the worst case, this can lead to exponential algorithm running time and to catastrophically bad performance.

To limit the amount of cell re-entrance, the Umbra 3 runtime culling algorithm traverses the graph in a mostly breadth-first fashion. Instead of a geometric portal solver, software rasterization is used to gather the visibility information into a screen-space occlusion buffer. This method almost completely eliminates excessive recursion. However, given the way the cells are built from the initial grid cubes, a true breadth-first cell processing order might not even exist: there can be cycles between the cells in the graph that leave no choice but to process a cell more than once.

To alleviate this, the graph is stored as box-shaped tiles, each holding tens to hundreds of cells. The tiles are generated in a way that a simple front-to-back order can be established between them. The per-tile traverse also makes the graph data access spatially coherent and, therefore, cache friendly.

The advantage of tiling is that once all cells in a tile have been processed, we know we have accumulated the final visibility information for all of them and, therefore, can safely release any resources held to capture the per-cell visibility.

The hierarchical tile graph traverse helps to manage the number of cells that are active at any given time. Another important memory optimization is the data layout of the occlusion buffer. Again, the fact that only conservatively correct results are required offers a cost-effective solution. The portal rectangles are rasterized into a low-resolution, 1-bit per sample, coverage buffer. Each set bit in the buffer represents an unoccluded path to the cell.

The concept of rasterizing empty space (the portals), instead of a representation of the occluding geometry, may at first seem unorthodox. However, rasterizing transformed quads allows easy conservative handling of geometry edges. The rasterizer makes half-space tests against the portal edge functions, saving computation resources in large inside or outside areas by hierarchically subdividing the screen rectangle and testing against rectangle corner pixels. Conservative rasterization also allows scaling the resolution based on the runtime platform performance.

The total amount of work memory required by the portal culling algorithm, including the traversal data structures, output depth buffer, and the coverage buffer for the active set of cells, is fixed to 85 kilobytes. This makes it small enough to fit in the local memory of modern stream-oriented processing units.

Occlusion testing of static objects residing in the cells can be done during the graph traversal by finding if there are visible pixels in the coverage buffer overlapping with the objects’ screen-space bounds.

Assigning static objects to cells is easy to do in the preprocess phase, where we can afford to work in the voxel representation. However, any dynamic entities that we want to test will require a different solution. For this purpose, the culling algorithm builds a global depth buffer during the traverse. The depth buffer of each traversed cell is updated based on the current coverage buffer, where the cell bounding box far distance is used as the depth-write value. In this way, only a single 16-bit 128x128 depth buffer needs to be kept in the memory for the duration of the traverse.

The ability to output a single depth buffer from the traverse enables making the dynamic object occlusion tests any time after the graph traverse. This can be particularly important if the exact position and extents of animating objects are to be determined in parallel with running the portal culling traverse.

Image 5: A downsampled depth buffer generated from occlusion data. From the left: the generated color buffer of a view in a game scene, the depth buffer used by the renderer and, finally, a much simplified view of the occlusion generated by the Umbra 3 culling system.

When pushing the envelope of the overall level of complexity that can be represented in a game, exact visibility information is an invaluable asset. Determining the elements that are not visible from a particular viewpoint is known as occlusion culling. Many approaches have been developed and employed to solve the occlusion culling problem. However, each traditional approach comes with a set of trade-offs and, therefore, occlusion culling remains an area of active research.

The Umbra 3 occlusion culling system was designed to overcome the trade-offs in the traditional occlusion culling solutions. Umbra 3 automatically processes any kind of polygonal input scene into a compact runtime representation. This representation can be used for efficient and conservatively correct occlusion culling. The key methods are:

The input geometry discretization at the voxelization process

The runtime software rasterization that quickly produces the list of visible objects alongwith a conservative depth buffer at the desired resolution

The portal graph and runtime resolution parameters allow the system to seamlessly scale from low to high end devices. Therefore, Umbra 3 is also a viable solution for, for example, smartphone games.

To sum up, Umbra 3 enables building massive 3D game worlds from random polygon soups without manual markup for visibility, while always guaranteeing conservatively correct culling results. Umbra 3 also makes visibility and spatial reasoning information accessible to a broader category of game engine subsystems. Because of this, game developers around the world, such as Bungie and many others, use Umbra 3 in various productions on a wide range of runtime platforms.

You May Also Like